An Interview with Nancy Haught, Author of Sacred Strangers: What the Bible’s Outsiders Can Teach Christians.

One of my favorite writers is Nancy Haught, an award-winning journalist who penned enriching articles on spirituality and religion for The Oregonian until her retirement. Her writing is always fair, decent, and humane. These are rare qualities and virtues in our society today. Never one for partisan polemics that dismisses those of different perspectives, Ms. Haught writes about her subjects respectfully and charitably. There is also a prophetic air in her work. This prophetic quality is present in Nancy’s new book, Sacred Strangers: What the Bible’s Outsiders Can Teach Christians (Liturgical Press, 2017). Just as she did as a newspaper reporter, so now, Nancy continues to reach out to people from various cultural and religious contexts. In Sacred Strangers, she reaches out to “outsiders” from various walks of life in the Bible. In the following interview, I ask my distinguished colleague to share about her volume and its import for today.

Paul Louis Metzger (PLM): Nancy, thank you for your willingness to be interviewed about Sacred Strangers. What inspired you to write this book?

Nancy Haught (NH): Thank you, Paul, for this opportunity. As a religion reporter, the best and the worst part of my job was calling strangers and asking them to share their deepest beliefs and trust me to represent them fairly in the newspaper so that people they didn’t know could read them. But over and over, strangers agree to talk to me. And often someone that I might otherwise dismiss, dislike, disdain or dodge completely became the source or subject of a good story and taught me something about my own faith and understanding of the world. I used to come home and tell my husband these stranger stories, and he often suggested I write a book. At the same time, as I studied scripture, I was intrigued by reading biblical stories from the secondary characters’ points of view. That is a way, I think, of getting at the deeper meaning, especially in familiar texts. And, as it turns out, in many Bible stories, strangers are supporting players.

PLM: What is the aim of the volume, and what do you hope readers will take away with them upon reading your meditations and reflections?

NH: This book is my effort to counteract the “be afraid of strangers” message that we are hearing from so many fronts. I think that narrative is a deliberate attempt to create divisions among all of us. If we are taken in by it, we divide people into those who are like us and those who aren’t and, too often, we don’t want anything to do with them. We see them as less than us; we assume they can’t teach us anything. But in both the Hebrew Bible and Christian Scriptures, strangers emerge as wise, resourceful and compassionate, even when they don’t adopt our religious beliefs.

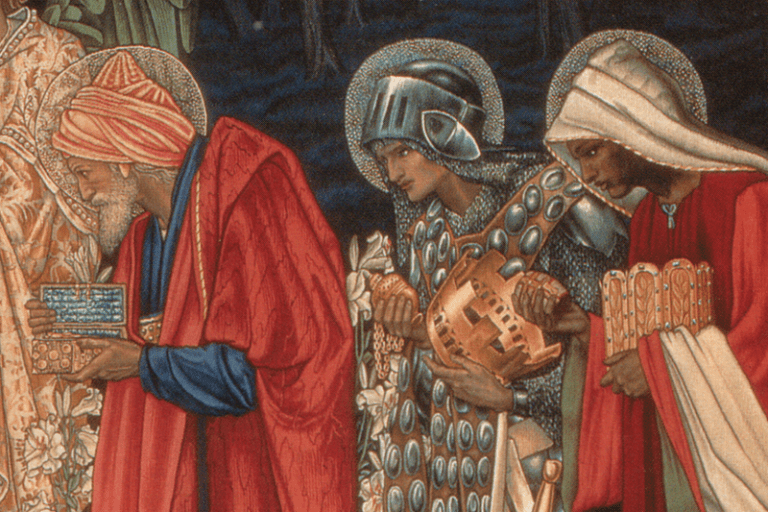

PLM: Let’s zone in on one of the stories that has special significance for many people during the Christmas season—the Magi. What do you find so compelling about the Magi—often called “wise men,” as Matthew’s Gospel presents their story (Matthew 2)?

NH: I love that the magi — total strangers — are part of Matthew’s Christmas story. When you think about it, they weren’t Jews, probably never became Christians and certainly weren’t Muslims. They come “from the East,” not even a country of their time. We don’t know what they did for a living, or even how many of them there were. But their actions in the story, especially their interactions with Herod and his advisors, show them to be open, honest, humble, determined, courageous men of integrity. And, beyond all that, they were men of vision. If we set aside Mary and Joseph, and maybe the inn keeper, the first people to see Jesus and recognize him as the king of the Jews (long before that designation is hung over his head at the Crucifixion) were strangers, foreigners, unknown, unrecognized, undocumented and unverified outsiders. Herod and his associates, the insiders in this story, are ignorant, petty, selfish, careless and cruel. So, who is it we should emulate as we try to live out our faith?

PLM: What other biblical stories do you cover in this book as an investigative reporter? What were two or three of your biggest “Aha!” moments?

NH: I did approach these stories as a reporter — read them in different English translations, read all the scholars I could find who had commented on them, prayed over them, talked to my teachers and other writers. And, just as it was when I was a reporter, there were a lot of surprises. From the Hebrew Bible, I read about Hagar, who had the courage to call God by the name she gave him, based on her own experience; Rahab, who was truly caught in the middle and found a way to save her family; and Naaman, an enemy general who, the Bible says, was victorious because God was on his side. From Christian Scriptures, I write about the Samaritan woman at the well who more than holds her own in what may be Jesus’ longest dialogue in the Bible; the Syrophoenician woman who pleaded for her daughter; and the Magi. A couple of “Aha!” moments? Realizing that it was a little girl, captured and held as a slave, who set in motion Naaman’s story, which is a study in what it means to be a servant. And reading what happens when that mother catches Jesus with, as one writer said, “his compassion down.”

PLM: I believe it is increasingly difficult today for us to reach out to those we deem outsiders. We have become increasingly tribal in so many contexts—religiously, politically, nationally—across the globe. Why do you think this is the case?

NH: I have heard a lot of different theories. But I suspect it has something to do with our mistaken belief that there is not enough of anything good — water, food, shelter, money, education, health care, jobs, what have you — to go around. If we fall for that lie, we are vulnerable to people who encourage us to hoard what we have and blame others when it seems we don’t have enough. I think the Syrophoenician mother reminds Jesus — and the rest of us — that there is enough to go around.

PLM: One of the most striking features of Jesus’ life and ministry is how he broke out of established structures of association and etiquette. All we need to do is consider how he associated over meals with tax collectors and sinners, and connected in vital ways with Samaritans and Gentiles. Holding firmly to our versions of the truth does not entail having to renounce those outside our sub-cultural comfort zones. What are some concrete steps we can take to hold firmly to our convictions while at the same time reaching out graciously to others? How might your book help us take those constructive steps?

NH: I think it’s an intentional process. We have to look for opportunities to meet people who are strangers. We have to force ourselves to talk to them and listen, not to interrogate them, confront them or try to convert them. This takes practice. But if our beliefs are deeply held, talking to a stranger will not change our convictions. Maybe it will help us see them more clearly or find a way to better describe our experience. It is a matter of trust, I think, being willing to trust God, our own experience, and even a stranger. I liked your blog post titled “Be Aware, Not Wary. Make This Your Dominant Outlook on Life.” There are times to be careful, but probably more times to be open. The poet Kim Stafford tells a story about his father, William Stafford, once Oregon’s poet laureate. Kim says that when he was growing up and leaving the house, his dad would tell him to remember to talk to strangers. Otherwise, he wouldn’t be able to find his way. He wouldn’t learn anything and might not be able to complete his journey.

PLM: In closing, I wish to draw attention to a mind-blowing emphasis among some theologians in your Roman Catholic tradition: Jesus is the supreme host and ultimate guest. We find this teaching on display in Christian Scripture—for example, Matthew 25’s account of the sheep and goats. There we find Jesus judging the nations as Lord who welcomes the welcoming to enter his kingdom. But in this same account in Matthew 25, Jesus also claims to be the stranger who people either welcome or exclude. This haunting passage in Matthew’s Gospel should awaken us to be more attentive to Jesus’ lordship as heavenly host and as hallowed stranger. Based on your book, Sacred Strangers, how would you encourage us to become more attentive to this twofold reality among the strangers in our midst? Thank you.

NH: I realized as I wrote this book that insider and outsider are fluid categories. Within the same story a character can, at times, be either or both. Jesus illustrates that and calls us to it, as well. Scripture often asks us to believe two different things at once. That doesn’t come easily to us sometimes. But it’s a skill we need to practice. If this book encourages us to set aside our stereotypes, ask questions, listen carefully to the answers, watch what strangers do and how they do it, be persistent in our search for common ground — even if it’s only a sliver — simple encounters will become relationships. And we know that relationships can change lives, mine and yours. Thank you, Paul, for your thoughtful questions.