Over at The New York Times, Frank Bruni wrote on the subject of “Trump’s Relentless Tribe.” Partisanship is serving the current occupant in the Oval Office well, as Bruni convincingly argues. Still, I believe, if the Democrats had won, the same would have been the case for their victorious candidate of choice. Thus, I disagreed with Bruni’s assessment when he writes, “I doubt that Democrats, faced with a leader like Trump, would fall this pathetically into line. Bill Clinton and his presidency foreshadowed without remotely matching this.” But Clinton was then. This is now: partisanship has reached new heights. As Bruni succinctly states just a few lines prior to the Clinton reference, “Forget I’m O.K., you’re O.K. This is: I have problems, you’re repulsive.”

Social psychologist Jonathan Haidt refers to this negative partisanship in terms of the sentiment of disgust, and maintains that the left-right divide is the greatest challenge we face today in American society. The other side–no matter which side–is a “basket of deplorables,” to use 2016 Democratic Presidential candidate Hillary Clinton’s unfortunate phrase.

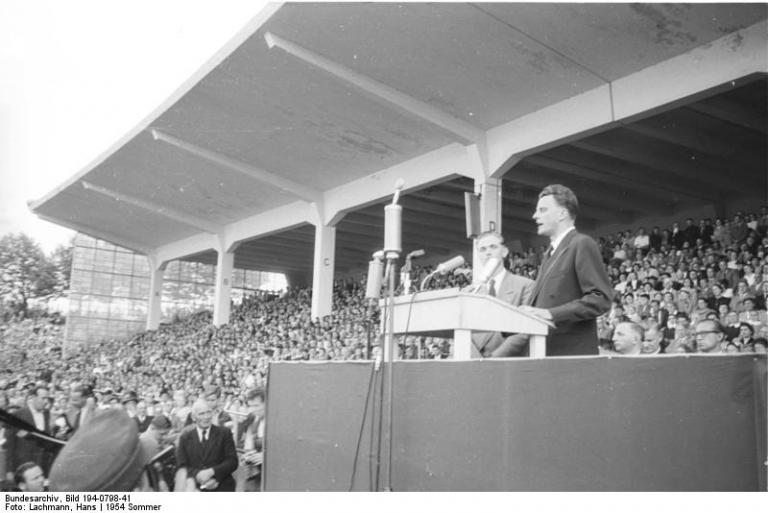

Partisanship may be serving President Trump well, but is it serving Evangelicalism well? What will such partisanship mean for Evangelicalism, where a very solid majority of white Evangelicals voted for Trump and affirm his social agenda? What will such partisanship entail for our concern for evangelism and evangelistic impact? Have we forgotten the lesson Billy Graham learned so painfully decades ago–to guard against political partisanship and against identifying with a particular political ideology?

White Evangelicals may find it increasingly difficult to evangelize anyone but ourselves if the report is true that we are cultural outliers. If, as one recent article claims, we are outliers who are out of step with other religious groups in the U.S. on our view of the direction of this country, will it entail for us an inability to reach those outside our fold? The Apostle Paul said he became all things to all people to save some. Are white Evangelicals like me becoming all things to some people–those like us–to save only them? If so, we will likely be saving less and less.

We who are white Evangelicals may be deceived into thinking that given our political prowess, our evangelistic prowess is on the increase. But I highly doubt that is the case. The same article claims, “As a group, white evangelicals are declining. A decade ago they made up 23 percent of the U.S. population; today it’s more like 15 percent,… But they have an outsize influence at the ballot box because they tend to vote in high numbers.” A high turnout at the ballot box is one thing. A high turnout for the altar call is quite another.

I do not wish for white Evangelicals to sway from biblical convictions. But are our convictions biblical and value-based, or are they nostalgia-based at various turns? Do we wish for a return to a cultural Christian past that favored white Christians, as the article referenced above entertains? That is the sense many outside our movement have, and as a recent poll conducted by the Public Religion Research Institute and The Atlantic conveys, according to Religion News Service:

As a group, white evangelicals were also the least likely to view America’s changing racial demographic makeup positively. Fifty-two percent of white evangelicals said they felt negatively about the prospect that nonwhites would become the majority of the population by 2043. That fits with white evangelicals’ approach to immigration, their distrust of Muslims and support for a border wall with Mexico. By comparison, all other religious groups in the survey viewed the changing demographics in mostly positive terms.

Are we aware of these perceptions? Do we take to heart polls that do not necessarily paint us in a favorable light, or do we write those reports off at every turn as examples of fake news?

If we are as concerned for evangelism as we are for politics, and if we take to heart what the Apostle Paul writes of becoming all things to all people rather than some, we should be willing to listen more to our critics, not so that we would cease being Evangelicals or evangelistic, but that we would be better witnesses to people outside our demographic and partisan political tribe.

Here’s the full context of the Apostle Paul’s statement:

For though I am free from all, I have made myself a servant to all, that I might win more of them. To the Jews I became as a Jew, in order to win Jews. To those under the law I became as one under the law (though not being myself under the law) that I might win those under the law. To those outside the law I became as one outside the law (not being outside the law of God but under the law of Christ) that I might win those outside the law. To the weak I became weak, that I might win the weak. I have become all things to all people, that by all means I might save some. I do it all for the sake of the gospel, that I may share with them in its blessings. (1 Corinthians 9:19-23; ESV)

If Paul were here today, who would he become like? Would he get beyond partisan ways and the political right-left divide?

My colleague, journalist Tom Krattenmaker, wrote a powerful manifesto titled Confessions of a Secular Jesus Follower. Tom is a representative of the cultural left in many ways, but he is also surprisingly to many outside his demographic a powerful witness to Jesus in amazing ways. There is a sense in which Tom has learned from the Apostle Paul that he needs to step outside his cultural norm. How does Tom step outside his cultural norm? He is more transparent and honest about the partisanship that impacts all of us. Not only does Tom see the bias and partisanship on the right, but also he sees it in himself. In his excellent book, he reflects the kind of soul-searching required of all of us:

There was the Senate Republican leader who, in the aftermath of Barack Obama’s election as president, declared that the opposition’s strategy going forward would be making sure Obama’s was a one-term presidency—not crafting and advancing a slate of bills, not tackling the public’s problems, but getting a rematch with the despised Democrat president and beating him the second time around. There were all the times I had evaluated candidates on my side of the aisle not on the basis of who had the best policies and character, but who had the best shot at sticking it to those bad guys on the other side and giving me and mine a taste of sweet victory (page 186).

If only we who are white Evangelicals could be known for the kind of soul-searching that Tom reflects. If only we would be willing to listen to the critiques of those who challenge our political and cultural predictability at various turns. If we don’t, I fear we will become increasingly less things to a smaller group of people, and reach only ourselves.