This is the third reflection for the Season of Creation, which is part and parcel of church liturgy in many traditions. With this point on liturgy in mind, it is fitting that consideration be given to the creation narratives in Genesis 1 and 2 as liturgical texts. The creation as a whole, and specifically Eden, functions as God’s temple over which God rules and humanity serves as priest.

We will discuss liturgy and temple in the context of addressing the second day of creation. On the first day, God declares that there be light. According to John Walton, “Day 1 speaks of time. Even if one thought it was about light, we cannot assume a physicist’s concept of light—we have to think like ancient Israelites. Day 1 includes nothing material.” If the first day speaks of time, the second day speaks of inhabitable space:

And God said, “Let there be an expanse in the midst of the waters, and let it separate the waters from the waters.” And God made the expanse and separated the waters that were under the expanse from the waters that were above the expanse. And it was so. And God called the expanse Heaven. And there was evening and there was morning, the second day (Genesis 1:6-8; ESV).

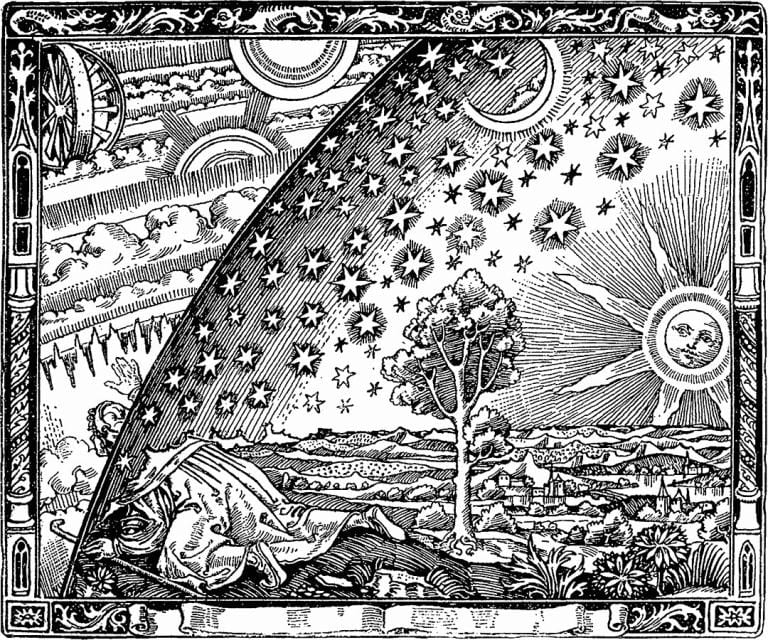

In Genesis 1:6-8, we find that God makes an expanse or firmament. Peter Enns claims: “The Hebrew word for this is raqia (pronounced ra-KEE-ah). Biblical scholars understand the raqia to be a solid dome-like structure. It separates the water into two parts, so that there is water above the raqia and water below it (v. 7). The waters above are kept at bay so the world can become inhabitable.”

According to Walton, Enns and other biblical scholars, we need to embed our understanding of the creation narratives in their ancient context rather than view them with modern eyes. One scholar claims that in the biblical world and the surrounding context, a connection was often made between cosmology and temple liturgy. I will position this point in relation to the inhabitable space involving the canopy in what follows in this post. Jeff Morrow puts the matter about cosmology and temple liturgy in this way: “This association between Temple and creation is not unique to the Genesis text…In fact, temples throughout the ancient Near East often had cosmological connotations. The building of a temple often accompanied creation, as we find in the Enuma Elish and elsewhere.” That does not mean that the Genesis story is enslaved to the ancient near-eastern world. It challenges it at points. My colleague Karl Kutz, who has also written on the Genesis creation account, shared with me that the canopy image in Genesis 1:6 demonstrates that God situates the biblical account against the backdrop of the pagan myths, but then reframes the canopy image so that it is viewed not as part of God (or as a god) as one finds in many myths, but as declared into being by God.

To return to the point on liturgy, temple and inhabitable space, the ultimate aim in God forming the canopy and making the earth inhabitable is so that humanity can dwell and rule in the creation as an expression of worship. Morrow, to whom I referred above, claims that Eden is the Holy of Holies of God’s temple of creation and humanity is its Homo liturgicus. He concludes his treatment of the creation account in this way:

If Eden is the Holy of Holies in God’s Temple of creation, the implication is that humanity, created for this inner sanctuary, is best understood as Homo liturgicus. Living in the Holy of Holies, humanity is called to give worship to God in all thoughts, words, and deeds. When we look at the Genesis account of Eden, we find other instances of people portrayed as created for worship. Adam, for example, is told to “till” (from the root ‘bd) and “keep” (from the root šmr). When šmr and ‘bd occur together in the OT (Num. 3:7-8; 8:25-26; 18:5-6; 1 Chr. 23:32; Ezek. 44:14) they refer to keeping/guarding and serving God’s word and also they refer to priestly duties in the tabernacle. And, in fact, šmr and ‘bd only occur together again in the Pentateuch in the descriptions in Numbers for the Levites’ activities in the tabernacle. Such an association reinforces the understanding of Adam as a sort of priest-king, or even high priest, who guarded God’s first temple of creation, as it were. In light of this discussion, therefore, what we find in Genesis 1-3 is creation unfolding as the construction of a divine temple, the Garden of Eden as an earthly Holy of Holies, and the human person created for liturgical worship.

Against this backdrop, it appears fitting to view the canopy as containing God’s tabernacle or temple where God meets with us and where we serve as priests in Eden and in creation as a whole. As we will see when we get to the end of Genesis 1 and beginning of Genesis 2 in this series on the Season of Creation, God rests or rules from his temple. According to Walton, God ran the cosmos from the temple. For Walton, God resting (See Genesis 2:2) entailed God getting down to business and ruling over the creation he had ordered. It did not entail taking a break.

God did not go off on holiday at the end of ordering the world and Eden for our habitation. God continues to rule. When we rest on the Sabbath, we are to remember that we ourselves are not God, and that the world is not God. We serve God who continues to rule over the entire temple of creation. We are to remember that we serve throughout the week and throughout life as royal priests in creation whereby we cherish and guard the creation as God’s temple in worship of God.