It is my privilege to interview Dr. Robert James Sutherland, a neuroscientist at the University of Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada, In this interview, we discuss the increasing challenges scientists face in pursuing their calling in view of various obstacles, including the charge that science is “fake news”. Here is Dr. Sutherland’s bio, which is adapted from his faculty page at Lethbridge. Dr. Sutherland received his PhD in Psychology from Dalhousie University in Halifax, Nova Scotia. He moved to the Department of Psychology at the University of Lethbridge in 1980, completing postdoctoral training in Neuropsychology on a NSERC Fellowship. From 1981 – 1991, he was a faculty member in Psychology. Then he accepted a position at the University of New Mexico, where he was Professor of Psychology, Physiology, & Neuroscience and Head of the Behavioural Neuroscience Area from 1991 – 2001. He then returned to Lethbridge, where he is Professor of Neuroscience, Adjunct Faculty in Health Sciences, Board of Governors Research Chair in Neuroscience, Chair of the Department of Neuroscience, and Director of the Canadian Centre for Behavioural Neuroscience (CCBN). Dr. Sutherland’s current research investigates the neurobiology of learning, memory, and amnesia in rodents and humans.

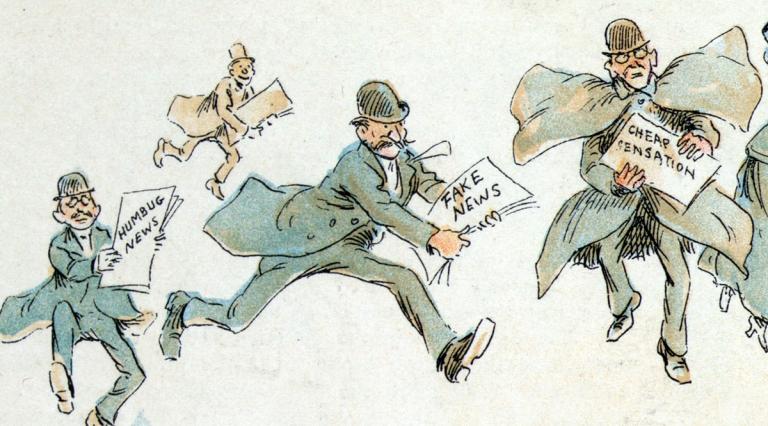

Paul Louis Metzger (PLM): Dr. Sutherland, this past year, I commented at a blog post titled “Three Essential Traits for Scientific Exploration and for Life” that “It is getting harder for scientists to do their jobs today. As one scientist with a career in politics claimed, in a world where science is often mistrusted as a form of fake news, one finds opinion having greater weight than evidence.” What are your thoughts in response to this quotation?

Robert James Sutherland (RJS): I really appreciate the opportunity to address this important topic. After focusing my professional activities toward science for the past 45 years, I can report that the level of mistrust and antagonism toward science and scientists has never been so high and never from such a wide range of constituencies. The main point of science as an occupation is to discover increasingly deep levels of understanding of nature, to disseminate this knowledge as widely and effectively as possible, to enrich people’s lives, and to reduce suffering. However, it is becoming more difficult for scientists to pursue these aims in the light of more and greater obstacles than a generation ago, including the charge of “fake news”.

PLM: In your estimation, what might be some of the cultural and neurological factors that lead to such distrust of science, including the charge of “fake news”?

RJS: This is a very big question. I am afraid I can only scratch the surface here. First, it is important to recognize that the distrust is coming from numerous quarters, not respecting some of the more traditional fault-lines. For example, we see antagonism toward science arising from the left and right wings of the political spectrum, from the rich and poor, from the religious and non-religious, and from people with a college education as well as from those who did not complete secondary school. Second, it is surprisingly rare for scientists to speak directly to the general public about their research. By “scientists” I mean people who apply the scientific method in their occupations. Nearly all the messages about science come from people who are talking about science rather than doing science. A generation ago most of those messages tended to be educational. Now, although there are some notable high-quality exceptions, there has been a dramatic decline in science journalism, as part and parcel of a significant decline in journalism generally. Teachers of K-12 tend to have only minimal exposure to science and mathematics in college. Moreover, in North America the number of college students who major in science or math, or who take more than the minimum number of science courses, is decreasing. This is occurring at a time when an increasing number of problems we are facing has a scientific component. A large proportion of the messages that people are exposed to is found on the internet and social media. The relative lack of messages from those doing science, or from good science journalists, leaves the marketplace open for messages from other sources and outlets that are talking about science. These sources generally have interests that are independent of science or are often increasingly opposed to science. Without good science education, the majority of people are very susceptible to sampling messages that represent confirmation bias, cherry-picking, or echo chambers of various types. When presented with valid scientific information that contradicts the main thrust of messages they have been attending to, people often reject the scientific claims and arguments. The tendency is to label the science as “fake”. Sources of information often have financial or ideological interests in conflict with the major body of scientific evidence, and yet they present their information as if it is in line with scientific findings. For example, readers may have come across advertisements claiming that solid scientific evidence supports buying products derived from jelly-fish. Readers may have also viewed advertisements offering on-line cognitive therapy for preventing age-related memory decline. The fact of the matter is that there is no solid scientific evidence supporting either advertisement. As scientists continue trying in various ways to test the effectiveness of these products, and if their findings continue to refute the advertisement claims, an abundance of refutations will likely appear in future advertisements challenging the scientific findings. Unfortunately, many in the general public conclude that science is simply untrustworthy, fake, or unable to tell a straight story rather than reflect on the problematic role of financial interests in promoting products. This has played out many, many times in the public domain where messages from people talking about science are confused with the actual evidence produced by people doing science.

PLM: We had opportunity to interact last year at an American Association for the Advancement of Science event in support of their Science for Seminaries program (through Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion). During the gathering, we discussed how the media’s portrayal of scientific debates over advances in science may play a role in the perception of science as “fake news”. For example, one often reads news reports detailing how recent studies challenge long-standing positions in the scientific community. Such reports can easily lead the general populace to think that science is merely about whose opinion gets the most publicity and is most popular. How would you encourage people to sift through these reports? How does “peer review” (which has come under increasing scrutiny—refer here and here for examples) and the scientific method come into play in evaluating the difference between scientific progress and the latest opinion poll fad?

RJS: Science, as a way of generating increasingly deeper understanding of nature, will always be changing. In most of the domains of science there is very little flux. The maximum speed of light or the mass of an electron or acceleration of falling bodies do not attract headlines, but the fact is much of the evidence in most scientific fields is relatively settled. Established research as well as state-of-the-art, effective tools and novel approaches are brought to bear on the frontiers so that new discoveries combine with long-standing scholarship to create increasing consensus (and, in some cases, even a new, alternative consensus). Certainly, work on the scientific frontiers is messy, so much so that the narratives about the frontiers may appear to the untrained eye and occasional observer to suggest that scientific pursuits are in a frantic and chaotic state. To the contrary, there is an underlying cohesion and sound methodological development in the midst of the various changes that must be accounted for and remembered at every turn. If the overall process were not in view, it would be easy to interpret the different stories that were being tested as an indication that scientists don’t know what they are really doing, that the scientific quest is all just one faulty, subjective opinion vs. another, and that science is unreliable. The news cycle and the internet capture the ferment at the margins. To restate and expand the points above, an emerging consensus eventually occurs many years later after the sifting of the new evidence using the imperfect though generally reliable peer review process. Unfortunately, the painstaking process takes so long, and the general public’s attention span is so short, that many will wrongly conclude that the scientific community does not know what it is doing. The damage is done and the consensus that emerges can be treated as just another story that the public can “believe in” or deny. Most scientists understand these two different time scales: long-term vision and short-term attention spans. While the day-to-day ferment is a source of great excitement for scientists, they realize that the science daily news will be treated with skepticism until the long-term sifting is nearly or entirely complete in relation to a large body of usually diverse types of evidence pointing to a clear answer.

Allow me to return to a previous question on what are some of the neurological or neurobiological factors that contribute to the problem of suspicion of science that we are discussing. There are some clear neurobiological factors that contribute to the rejection of scientific evidence and the embrace of the claim that science is generating fake information. I will mention three. First, the repetition of information leads the brain to process the same or similar information more rapidly. This leads to a sense or feeling of familiarity. A feature of the brain is that this “processing fluency” and consequent familiarity with the information leads to an “illusion of truth,” where the attendant emotional familiarity overcomes rationality. Second, there are multiple routes through the brain that can process the same event or information. At the most general level, one route is fast, recruiting emotional responses networks, and the other route is much slower, involving distributed knowledge networks in frontal and other cortical regions. Many decisions do not wait for the slow, thoughtful processes (for example, we respond using the fast system when asked “Is it a good idea to swim with sharks?”). Some recent research supports the idea that people who are more likely to accept fake news or conspiracy theories have a greater tendency to apply the fast system to decision-making in general. Third, it is well known that the impact of information is enhanced if it is presented with emotionally arousing cues. This phenomenon has been well-studied in the context of stimulation of emotional networks and neurochemicals strengthening the consolidation of memories. Fake stories, conspiracy theories, and a great deal of advertising take advantage of this memory consolidation effect. A solid presentation of the relevant scientific information by an expert rarely takes advantage of this effect.

PLM: You indicated in a prior conversation the need for scientists to get out and build trust with the surrounding community so that people truly understand that science seeks to serve the common good (The same is true for theologians, I might add! We need to build trust with the scientific community and culture at large by demonstrating that we seek to promote the common good as well). What barriers and obstacles might there be for scientists to engage in such bridge-building efforts?

RJS: The communication skills of scientists leave a few things to be desired. Much of what scientists learn about communication is directed toward three things: writing effective scientific journal articles or grant applications targeted exclusively at other relevant scientists; delivering presentations on their research at meetings of other scientists; and delivering lectures or seminars to college science students. None of that prepares a scientist to communicate effectively in the surrounding community. There are few opportunities for scientists to learn those forms of communication. Even worse, the incentives for scientists rarely include rewards for effective discourse with the wider community. Never would this kind of activity increase the likelihood of tenure, promotion, or garnering needed resources for research. There is a big disconnect between the funding importance of communication in the wider community and the structure of science as an occupation. We need to create strong incentives for scientists to cultivate effective communication skills for engaging the public and to be motivated to be more visible and successfully interact with the broader populace. Now it is typically only when scientists are reaching the end of successful careers and have already reaped most of the available rewards that they turn their attention to the interests of the wider community. When they do so, it quickly becomes clear that lots of people are hungry to hear directly from scientists and find those forms of interaction to be uniquely clarifying and enriching. I personally find communicating with the general public or select non-science groups—whether it is about how the brain works or about general science—to be challenging and extremely rewarding. There are exceptions, however. A couple of examples come to mind. Attending meetings of certain groups committed to “alternative” health interests or to young earth creationism, where I have tried to clarify the scientific consensus on relevant topics, has led to strong reactions that were less than polite and ad hominem. It is clear that there must be some prior commitment to sincere and civil dialogue if communication involving all parties is to be effective.

PLM: What closing thoughts would you like to share with our readers?

RJS: Like every aspect of human activity, science is imperfect. We get things mixed up and often cannot determine the right approach to a problem. Although we have a solid methodology, we advance by trial and error. In fact, we often make progress even when we are wrong! The short-term turmoil on a given topic of research is plainly visible to the wider community. Further to what was stated in a previous response above, the time-scale of the normal public news cycle and anti-science interests take advantage of this perception of the short-term turmoil. Take, for example, the regular news reports about Alzheimer’s disease. This is a frontier region in neuroscience and has all the characteristics I described earlier. We hear about a new cure or new theory seemingly every week because there is only very limited evidence available to us right now. As with every frontier the amount of evidence is growing dramatically, but we cannot clearly see just yet what it means. Scientists take a calculated shot at getting the story right, but in these early days it is unlikely that they will have it right. However, I am confident that over the next many years a consensus will emerge, and we will have a deep understanding of what has gone wrong in the Alzheimer’s brain. We will then be able to reduce the wide suffering associated with this condition. At the frontiers we need to exercise healthy skepticism. After the consensus emerges, we need to spread far and wide the hard-won understanding for the sake of human flourishing.