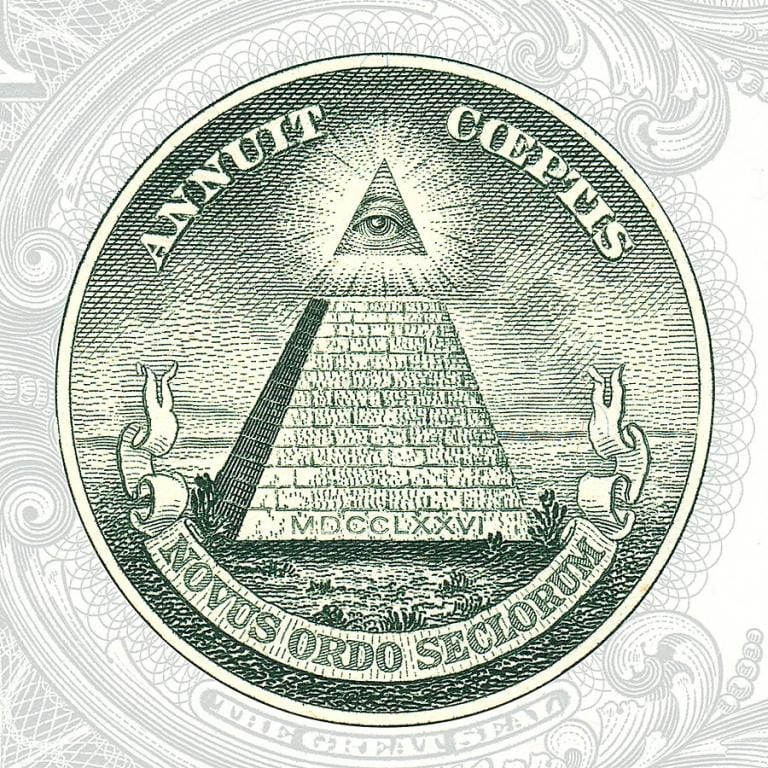

There’s a lot in the news these days on conspiracy theories. My colleague John W. Morehead and I have been reflecting upon conspiracy theories, too. In fact, we are doing a series of posts here at my blog column on the subject. If we step back and look at the sweep of American history, we may be surprised to know that there has often been a predilection for such theorizing. It’s in the tap water or in the ‘Covid’ air—just like a conspiracy theory might claim. Maybe you know someone who is a conspiracy theorist or an adherent. Then again, how would you even know? Why does it matter that we discuss this subject? How harmful or healthy could theorizing about conspiracies really be?

To address many of these types of questions, we reached out to Joseph E. Uscinski (JEU), who is Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Miami. He studies public opinion and mass media with a focus on conspiracy theories, misinformation, and disinformation. He is the coauthor of American Conspiracy Theories (Oxford, 2014), editor of Conspiracy Theories and the People Who Believe Them (Oxford, 2018), and author of Conspiracy Theories: A Primer (Rowman & Littlefield, 2020). Here are the questions John Morehead and I asked. You can find Dr. Uscinski’s answers in the video at the close of this blog post.

John W. Morehead (JWM): In an essay in Argumenta, you stated that “conspiracy theories” is loaded terminology. Why is that and how would you define “conspiracy theories”?

JEU:

PLM: There are certain assumptions and stereotypes about who believes in conspiracy theories. What are they? Is everyone susceptible (if that’s the correct term) to believing in them? Regardless of the answer to this question, what makes some/or all susceptible?

JEU:

JWM: Why does this matter? Are they just theories, or do they have negative and possibly dangerous import? What kind of decisions are people making as a result of conspiracy thinking influences? How is such thinking shaping our society?

JEU:

JWM: How does partisanship and proximity to power play a part?

JEU:

PLM: In our current political context, more people are becoming aware of and talking about QAnon, including its popularity on the right. What are some other popular conspiracy theories of the past and present across the ideological and political spectrum? How far back does this go in American history?

JEU:

JWM: In your book Conspiracy Theories: A Primer, your final chapter discusses conspiracy theories related to President Trump. Can you discuss some of these and how the internet has contributed to them?

JEU:

JWM: In your Argumenta essay noted earlier, you argue that conspiracy theories should not be treated as wrong, and that they are necessary to the healthy functioning of society. This will be a hard pill to swallow for some and may sound confusing in light of what was discussed previously during this interview. Could you please unpack what you were getting at in the Argumenta essay along these lines?

JEU:

PLM: Last but not least, how would you encourage us to engage conspiracy theories and their adherents in conversation in order to foster healthy discourse for societal flourishing?

JEU: