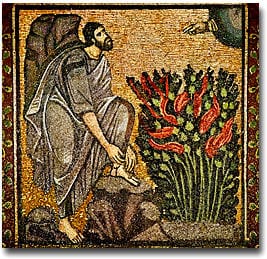

Why did Moses ask God to provide his name at the burning bush scene (See Exodus 3), and what did/does God’s personal name mean? We will address each question in turn, beginning with “Why?” This is the second post in a three-part series on how we approach naming in contemporary culture and God’s name in view of Scripture. Refer here for the first post in this series titled “Don’t Name Drop for Fifteen Minutes of Fame.”

Someone’s personal name in our American culture today does not often convey the weightiness it did in biblical times. A name does not necessarily say anything about us. Rather, it often functions simply as a place holder to be occupied later by the lives we lead. But it’s different in the biblical world. What’s in a name biblically? Identity, character, prophetic disclosure, family connection, reaction, and story. God discloses to Abram that he will no longer be called Abram, but Abraham, for God will make him the father of many nations (Genesis 17:1-6). God tells Abraham that his son will be named Isaac (Genesis 17:19), which signifies laughter, likely conveying a combination of his parents’ disbelief over his unnatural birth in their old age, joy, and even ridicule in the sight of others. God tells Jacob that he has wrestled with God and man and has overcome. And so, God changes his name to Israel (Genesis 32:28). Last but by no means least, God’s angel tells Joseph that Mary will give birth to a son by the Holy Spirit and that he is to be given the name Jesus meaning salvation, for he will save his people from their sins (Matthew 1:21). We see the importance of one’s name on full display when God appears to Moses at the burning bush recorded in Exodus 3:13-17:

Then Moses said to God, “If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I am who I am.” And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘I am has sent me to you.’” God also said to Moses, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you.’ This is my name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations. Go and gather the elders of Israel together and say to them, ‘The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, of Isaac, and of Jacob, has appeared to me, saying, “I have observed you and what has been done to you in Egypt, and I promise that I will bring you up out of the affliction of Egypt to the land of the Canaanites, the Hittites, the Amorites, the Perizzites, the Hivites, and the Jebusites, a land flowing with milk and honey”’ (Exodus 3:13-17; ESV).

Why did Moses ask? For one, a lot is at stake. God is calling Moses and Israel to throw off their chains of slavery and leave Egypt for some promised land. Moses is not going to go back to Egypt for just any old deity that appears to him at a burning bush. After all, Pharaoh wanted him dead or ‘deader’ for having killed an Egyptian taskmaster for beating a Jewish workman. As a result, Moses fled Egypt and lived in Midian (Exodus 2:11-15). Moreover, Moses knows full well that Pharaoh is not going to take kindly to Moses running off with his ‘property’—slave work force.

Asking for someone’s name in a work situation entails accountability and responsibility in our society, if nothing more. We often ask a customer service representative on the phone for their name. In God’s case, God is holding himself accountable and responsible for fulfilling his promise and taking Israel out of Egypt and leading his people into the Promised Land. God does not need anyone else to hold him accountable, since he is who he is, he will be all that he will be, he will be the totality of who he is as the great I AM. In God’s case, his name and self-description says it all. Identity, character, family connection, and story come into play.

Having asked why Moses asks for God’s name, it is time to ask what does God’s name “the Lord,” that is “I am who I am” (first person) or “Yahweh”/“He is” (third person) mean? Here is what I argued in the book Connecting Christ: How to Discuss Jesus in a World of Diverse Paths:

The Bible teaches that God is exclusively one and that God is properly named. Exodus makes clear that the God revealed to Moses takes seriously his name, Yahweh, which English Bibles often render, “the Lord.” It is worth noting that the first explanation of the divine name is in Exodus 3:13–15. God articulates his name in the first person as “I am who I am.” To Israel, he gives the name Yahweh (“He is”) to remind them that he is who he is: God cannot be compared; God is self-defined. Exodus 6:2–3 indicates that God had never explained himself as Yahweh until revealing himself to Moses. His people had known him prior to this as El Shaddai.

Exodus 34:1–8 unpacks further what Yahweh means. Whereas the name El Shaddai reveals God as all-powerful in a general sense, the name Yahweh speaks to how God brings the totality of his essence and character into covenantal relationship, focusing primarily on mercy and deliverance. While God cannot be less than he is in the totality of his being—so that as God he must judge—the context of exodus 3 and 34 makes clear that God reveals his personal name to display his chief desire: to be merciful, redemptive, and in covenantal relationship. in Scripture God pours out his mercy on Israel and the church as Yahweh, creating and redeeming them and offering the promise of redemption to the nations through them.[1]

As time goes on, Moses will have a lot more divine self-disclosure to go on (for example, Exodus 33 and 34), as God demonstrates his faithfulness time and again to deliver on his promises through his presence and miraculous interventions. To this point in Exodus 3, Moses only had a recollection (no matter how vague) that his ancestors Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob worshiped El Shaddai, who had faithfully led them. In fact, God had led the Patriarch Israel and his family to Egypt. And now, God wanted to take them out! No doubt, this conversation took some time to process. Actually, the burning but still intact bush was the easiest part of the account to accept. The promised deliverance was going to take more convincing not only in Moses’ mind, but also in the minds of others.

Moses went to the people of Israel to inform them of his conversation with God at the burning bush. Moses’ brother and spokesperson Aaron had to reiterate what the Lord had said to Moses and perform all the signs that God had commanded. “Aaron spoke all the words that the Lord had spoken to Moses and did the signs in the sight of the people. And the people believed; and when they heard that the Lord had visited the people of Israel and that he had seen their affliction, they bowed their heads and worshiped” Notice that Israel now knows God as the Lord (Exodus 3:30-31; ESV). So far, so good. But Moses and Aaron still had to go to Pharaoh. More on that in a few moments.

In what follows, I wish to make a few comparisons: Moses’ initial exchange with God and Pharaoh’s initial exchange with Moses; the Bible’s account of empires and Jesus’ upside-down kingdom; and Moses and us. Let’s start with the comparison between Moses’ exchange with God in chapter 3 and the opening exchange between Moses and Pharaoh in chapter 5. Here are the two accounts:

Exodus 3:13-15 reads:

Then Moses said to God, “If I come to the people of Israel and say to them, ‘The God of your fathers has sent me to you,’ and they ask me, ‘What is his name?’ what shall I say to them?” God said to Moses, “I am who I am.” And he said, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘I am has sent me to you.’” God also said to Moses, “Say this to the people of Israel: ‘The Lord, the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac, and the God of Jacob, has sent me to you.’ This is my name forever, and thus I am to be remembered throughout all generations” (ESV).

Exodus 5:1-2 reads:

Afterward Moses and Aaron went and said to Pharaoh, “Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, ‘Let my people go, that they may hold a feast to me in the wilderness.’” But Pharaoh said, “Who is the Lord, that I should obey his voice and let Israel go? I do not know the Lord, and moreover, I will not let Israel go” (ESV).

Moses’ initial exchange with God and then Moses’ initial exchange with Pharaoh are very striking. Moses does not know the Lord who alone is God, nor does Pharaoh. And yet, they will come to realize soon enough who God is and what God is like. Whereas Moses asks God what his name is, Pharaoh asks rhetorically in Moses’ presence who is the Lord (God’s personal name) that he should obey. Reflecting on how the text plays out in the succeeding verses and chapters, it’s almost like God is saying (through Moses), “Thank you for inquiring, Pharaoh. I thought you’d never ask. Please allow me to introduce myself…” Not only does God answer Moses’ question and share his personal divine name (“the Lord”), but also he goes on to unpack what that name means and makes clear who and what he is like in the succeeding events leading up to and including Israel’s exodus from Egypt in answer to Pharaoh’s question.

It is worth noting here that Pharaoh and the Egyptians see Pharaoh as the mediator between the gods and humanity, and that he would become divine at death. Here’s what the Encyclopaedia Britannica has to say about “Pharaoh”:

The Egyptians believed their pharaoh to be the mediator between the gods and the world of men. After death the pharaoh became divine, identified with Osiris, the father of Horus and god of the dead, and passed on his sacred powers and position to the new pharaoh, his son. The pharaoh’s divine status was portrayed in allegorical terms: his uraeus (the snake on his crown) spat flames at his enemies; he was able to trample thousands of the enemy on the battlefield; and he was all-powerful, knowing everything and controlling nature and fertility.

No doubt, the supposedly divine Pharaoh took issue with Moses coming before him as a mediator or messenger of the slave people Israel’s “god”—“the Lord.” It is also worth noting here that God never speaks directly to Pharaoh, perhaps elevating further Moses’ status as his mediator/messenger and that he listens to Israel’s cry, not the one who made his people cry. Perhaps Pharaoh feels like God is adding further insult to the aggravation in that Pharaoh scoffed at what appeared to be an absurd and empty command, namely, that he—the divine ruler of the mighty Egyptian empire—should obey the voice of “the Lord”. Pharaoh likely perceived “the Lord” to be an unknown and irrelevant tribal deity. In Pharaoh’s mind, the Lord was certainly no match for Egypt and its imperial gods. How wrong he was, as the succeeding judgments in the form of plagues along with the Passover and ensuing Exodus make very clear.

Having compared Moses’ initial encounter with God and Moses’ initial encounter with Pharaoh, now let’s compare Scripture’s account of empires with God’s upside-down kingdom revealed in Jesus. Empires often treat their subjects as nameless and faceless. Bricks become more important than human beings. This was the case with Babel and with Egypt. Here’s what an article in the Jewish Bible Quarterly claims:

the project of building the Tower of Babel became of such paramount importance that bricks became more valuable than human beings. If a man fell to his death during the construction, no one paid notice. But if a brick dropped, the people wept (Pirkei de-Rabbi Eliezer 24). By negating the value of the individual, the builders of the tower denied man’s divine source and its attendant holiness. In so doing, they challenged God’s authority as Creator. Pharaoh’s goals were not wholly different. He, too, sought to challenge God’s authority. The Egyptian pharaoh was treated as divine, a representative of the gods on earth, if not a god himself.[2]

Given Pharaoh’s elevated status in Egypt, it is little wonder that he would feel justified in subjugating Israel to slavery. According to the great Jewish scholar Rashi, such dehumanizing subjection was ultimately aimed at discrediting Israel’s god[3] and elevating himself as divine.

How striking that God counters Babel’s builders’ aim in making a name for themselves (Genesis 11), not only by making people speak in different languages and thereby stopping the tower building, but also by making a name for Abram and blessing all peoples on earth through him (Genesis 12). God doesn’t try or need to make a name for himself. God’s name is eternal and glorious. Nor does God name drop. Rather, God makes a name for his no-name people. God gives no name people names that last whereas Scripture does not mention Babel’s builders’ names, nor the names of the pharaohs accounted for in Scripture. One article has this to say about the nameless pharaohs in the Torah:

Significantly, the Egyptians are equally nameless. The Midrash has to supply Pharaoh’s daughter with a name because the Torah omits one. Even the pharaoh himself is nameless. “Pharaoh” is the designation of his office, a political position, not a name. Historically, the Egyptian pharaohs all had names, yet the Torah pointedly omits them. They become anonymous persecutors of God’s nation. And this is the ultimate lesson of namelessness. One cannot deny the divine spirit in others without denying the divine spirit in all men. One cannot dehumanize others without dehumanizing one’s self.[4]

The Pharaoh accounted for in Exodus did not know Joseph. Interestingly, we do not know the pharaohs accounted for in Genesis and Exodus by name. But we do know Moses by name. Here is one of my favorite texts in all of Scripture:

By faith Moses, when he was grown up, refused to be called the son of Pharaoh’s daughter, choosing rather to be mistreated with the people of God than to enjoy the fleeting pleasures of sin. He considered the reproach of Christ greater wealth than the treasures of Egypt, for he was looking to the reward. By faith he left Egypt, not being afraid of the anger of the king, for he endured as seeing him who is invisible. By faith he kept the Passover and sprinkled the blood, so that the Destroyer of the firstborn might not touch them (Hebrews 11:24-28; ESV).

Moses identified with his enslaved people and considered the reproach of Christ of far greater value than name-dropping Pharaoh’s daughter and locking up Egypt’s treasures. He chose wisely. How about us? Do we name drop for fame and fortune or do we identify with Jesus, the God of the widow, orphan, alien, and slave in their distress?

What empire’s deities are you and I tempted to cater to and submit to today? How does the Lord God of Israel compare with these deities in your estimation? What difference does knowing God’s personal and covenantal name “the Lord” mean to you, and how well do you understand God’s character and what God is like? Moses will come to realize that rather than name-dropping that he was the son of Pharaoh’s daughter, draping himself along with the people of Israel in God’s name is worth the risk.

Having noted that Moses draped himself in God’s name rather than name-dropping Pharaoh’s daughter, let’s compare Moses and us. I am struck by Moses’ plea to God recorded in Exodus 33:12-16:

Moses said to the Lord, “See, you say to me, ‘Bring up this people,’ but you have not let me know whom you will send with me. Yet you have said, ‘I know you by name, and you have also found favor in my sight.’ Now therefore, if I have found favor in your sight, please show me now your ways, that I may know you in order to find favor in your sight. Consider too that this nation is your people.” And he said, “My presence will go with you, and I will give you rest.” And he said to him, “If your presence will not go with me, do not bring us up from here. For how shall it be known that I have found favor in your sight, I and your people? Is it not in your going with us, so that we are distinct, I and your people, from every other people on the face of the earth?” (Exodus 33:12-16; ESV).

Notice the growth in Moses since the burning bush episode recorded in Exodus 3. Moses has determined to lead the people out of bondage and to the Promised Land. He also desires to know God intimately. He begs God to show him his ways so that Moses might know God in order to find favor in God’s sight. Moreover, Moses asserts that the only distinguishing mark for him and Israel is their God. It wasn’t their new national identity or their ancestors or their immediate families or careers or possessions, but God. How about us?

In response to Moses’ plea, God assures Moses he will go with Israel, that he knows Moses by name, and when Moses asks to see God’s glory, God promises to disclose the divine name the Lord to Moses (Exodus 33:17-19). What do we ask God for? Far more significant than a brand name that defines a product is God’s name “the Lord” that defines his people. What do we who claim to follow Christ hope will distinguish us? Do we name drop celebrities? Do we find our ultimate hope, distinction and identity in a political party or career path, designer clothing, family, or name recognition? Or do we clothe ourselves completely in God’s triune name as we journey in the wilderness among the nations to the Promised Land? (Matthew 28:18-20) Given who God is and what his name as “the Lord” signifies—namely, that he is the eternal, all-sufficient and good God who keeps his promises to deliver his people out of bondage and lead them to salvation and fulness of life for eternal glory rather than fifteen minutes of fame—may we claim and proclaim the divine name. May we have Moses’ eyes to see what really matters, what really lasts, and what should distinguish us. May we go forward in God’s name “the Lord” or else come to a complete halt—even today.

In the final post in this three-part series, we will seek to discern how to claim and proclaim God’s name. We want to guard against failing to take God’s name seriously by ignoring it, but we also want to guard against taking God’s name in vain. So, how should we claim and proclaim the divine name today?

_______________

[1]Paul Louis Metzger, Connecting Christ: How to Discuss Jesus in a World of Diverse Paths (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2012), page 99.

[2]Sheila Tuller Keiter, “Outsmarting God: Egyptian Slavery and the Tower of Babel,” Jewish Bible Quarterly, Vol. 41, No. 3 (2013): 202.

[3]Rashi makes this point in his commentary on Exodus 1:20, “Our Rabbis, however, interpreted [that Pharaoh said], Let us deal shrewdly with the Savior of Israel.” Rashi, Commentary, Chabad.org, accessed on November 1, 2019, https://www.chabad.org/library/bible_cdo/aid/9862/showrashi/true/jewish/Chapter-1.htm.

[4]Keiter, “Outsmarting God: Egyptian Slavery and the Tower of Babel,” 202.