Rep. Adam Kinzinger, a Republican Congressman from Illinois, has spoken out about the loss of “moral authority” in the GOP. Refer here, for example. This week, he repeated his challenge to his party. Those GOP members of Congress who object to President-elect Biden’s victory today have lost their “moral authority” to take issue if Democrats return the favor and object to a future GOP Presidential election victory. Watch here. It raises the question: What constitutes moral authority in the US—or anywhere for that matter—today and always?

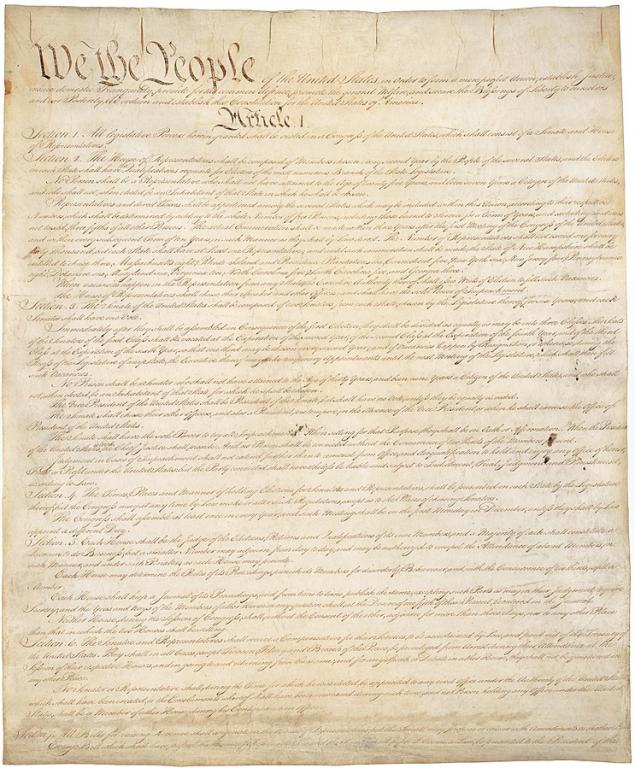

Is it popularity and public opinion, economic, political or military prowess, adherence to a country’s founding legal documents, pure reason, divine law, something else? Kinzinger states that adherence to the US Constitution dictates whether one has moral authority as a political leader in this country. His reflections remind me of the speech of General Mark Milley, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, which Milley gave at the dedication of the US Army Museum last November: “We are unique among militaries.” How so? “We do not take an oath to a king or a queen, a tyrant or a dictator. We do not take an oath to an individual.” Milley asserted that the military has an unambiguous duty to safeguard the Constitution, which he referred to as the “moral north star” for US military personnel. “We take an oath to the Constitution,” and “will protect and defend that document regardless of personal price.”

Regardless of one’s personal opinions regarding Kinzinger and Milley, one should take to heart Kinzinger’s call for consistency of conviction and adherence to the Constitution, as well as Milley’s call to protect the Constitution regardless of personal price. To the extent that they and we who are US citizens do that in our respective areas of service, we demonstrate moral authority. Certainly, we can seek legal amendments to the Constitution, as has occurred occasionally over our country’s history (take for example the 13th Amendment abolishing slavery). However, those amendments are intended to reflect the spirit and ultimate aims of the Constitution.

Our country’s founding fathers took stock of the French Revolution. One of the major influences on their thought was Montesquieu and his separation of powers. For the purposes of this present post, I wish to draw attention briefly to Montesquieu’s categories of government and see how they might bear on our current context in the US. His three categories that apply to various societies are despotic, monarchial, and republican. The founding fathers sought to create a republican society (not to be confused with the Republican Party) rather than a monarchial or despotic system. The ethos that shapes a despotic society is fear. Honor marks the ethos of a monarchial society. In contrast to these two frameworks, virtue characterizes a republic. In a despotic state, the motivation for obedience to the law is fear of the consequences of not obeying the dictates of the tyrant. In a monarchial state, the motivation for obedience to the law is honor and status. In a republic, the motivation for obedience to the law is esteem for civic virtue. The government must make serious efforts to educate its citizenry in civic virtue with all its attending demands (See Alasdair McIntyre’s articulation of these categories and critique of Montesquieu’s analysis of social life in chapter 13 of A Short History of Ethics).

Regardless of our political affiliations and desires, hopefully we all agree that what we need from our civic leaders today is consistency of character to uphold the US Constitution. How can the government train the citizenry in civic virtue if they themselves are swayed by political opportunism and opinion polls? For the rest of us, we need to make sure that we seek to embody moral authority by growing in civic virtue. As a child in my Republican family household, I used to reflect on a plaque that hung in my bedroom. It included the words of the late President John F. Kennedy’s inaugural address: “Ask not what your country can do for you – ask what you can do for your country.” Presidents Kennedy and Eisenhower understood the importance of this statement as the Republican Eisenhower (and famous World War II veteran general) supported the peaceful transition of power to the Democratic Kennedy (also a World War II hero). Eisenhower sat nearby as Kennedy uttered his inauguration speech. Our ultimate commitment as citizens in this country is not to this or that political leader, but to the Constitution, which serves as the “moral north star” for our whole country, not just the military. What can we do as citizens today? Grow in personal consistency of conviction centered around the Constitution, not a political leader, and personal sacrifice for the greater good, not simply for one’s political or cultural ingroup. After all, we are one nation under God and under the Constitution, not under President Trump or President-elect Biden, or a political party.