The most difficult transition in early Christianity, which of course began as a sect of Judaism, was the shift from the unquestioned monotheism–represented in the Shema prayer (“Hear O Israel! The Lord our God is one Lord!”)– to a burgeoning belief in God as a trinity of equal, unified, but distinct ‘persons.’ Unqualified and single devotion to Jahweh became complicated by the growing  sense that Jesus was also divine and therefore equally worthy of worship–as was the Holy Spirit. Debates raged, of course, as to whether Jesus was equal to God (see “Arius” and “Arianism”) or not, but eventually the Nicene Creed came to dominate the landscape and to determine what counted as Christian orthodoxy. Jesus was thereafter considered “of the same essence” as God the Father. But the “thereafter” took some working out. Things were still far from clear and even farther from a unified consensus.

sense that Jesus was also divine and therefore equally worthy of worship–as was the Holy Spirit. Debates raged, of course, as to whether Jesus was equal to God (see “Arius” and “Arianism”) or not, but eventually the Nicene Creed came to dominate the landscape and to determine what counted as Christian orthodoxy. Jesus was thereafter considered “of the same essence” as God the Father. But the “thereafter” took some working out. Things were still far from clear and even farther from a unified consensus.

The resurrection of Jesus was an important piece of the argument in favor of his divinity. But more than that, it changed the way early Christians understood the inner life of God. In The Spirit of Early Christian Thought, Robert Louis Wilken details this development by discussing the contributing of Hilary, the bishop of Poitiers. Hilary became an apologist for the Nicene decision on the divinity of Christ. When he was exiled by Emperor Constantius (who did not support Nicaea’s conclusions), he wrote a work called The Trinity.

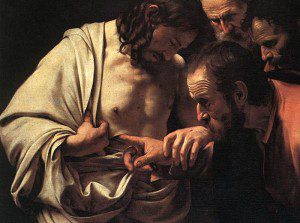

In this work, Hilary argued that Thomas’s confession upon seeing the resurrected Jesus, “My Lord and my God,” transforms our understanding of the Shema. How can God be “one,” if Christ and the Father are God? This insight was so counter-intuitive as to require a miraculous disclosure. As Wilkin puts it, “his disciples did not have eyes to see who he was,” and of course they were faithful Jews, so they understood God through the lens of Shema. The full recognition of Christ’s divinity had to await the event of the resurrection–thus its crucial importance. But once understood, it transformed their theology ,not just of who this Jesus was, but of who God is. Wilken explains:

After the resurrection he could continue to recite the Sh’ma because he had begun to conceive of the oneness of God differently. Thomas’s confession ‘my Lord and my God’ was not the ‘acknowledgement of a second God, nor a betrayal of the unity of the divine nature’: it was a recognition that God was not a ‘solitary God’ or a ‘lonely God.’ God is one, says Hilary, but not alone.

While progressive Christians should account for the obvious fallibility–and sometimes horrendously violent politics–of the story of the development of early trinitarian dogma (see, for example, Wendy Farley’s devastatingly honest portrayal in Gathering Those Driven Away, there’s some amazingly rich stuff in there, too. Here’s an example of a pretty cool idea. God is not a “solitary” or “lonely” God. God’s inner life is narrated by a plurality of persons sharing a single essence. The life of God is shaped by God’s acts within history. God’s involvement in creation through the Son’s incarnation and resurrection means that God is social, dynamic, relational–not “lonely.” This notion takes flight in contemporary theology, including in the “social trinitarianism” of liberation-oriented theology.

But it begins here with that starting insight about the resurrection: “My Lord and my God!”