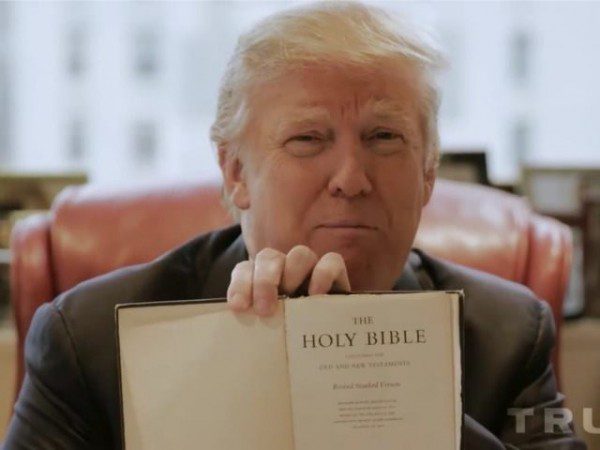

Religion gets a bad rap these days–and more and more so all the time, it seems. And for understandable reasons.

Anyone who has taken a church history class (or pretty much any history class, for that matter) is aware of the contribution of religion to humanity’s collective bloodshed. Prominent examples of Christianity’s role include the Crusades of the Middle Ages (1095-1291) and the “30-years war” in continental Europe (1618-1648), a war fought between Protestants and Catholics. In both cases, the violence was about more than just religion (it always is), but its role is undeniable, nonetheless.

It is often said that it was the bloodshed of the 30-years war that eventuated in the secular age of Europe. Who needs religion when all it’s good for is death and destruction? Today the “secular age” is complicated by the rise of new forms of religious fundamentalism; and of course, militant, radical Islam is a grave and constant threat in many parts of Europe–and across the world.

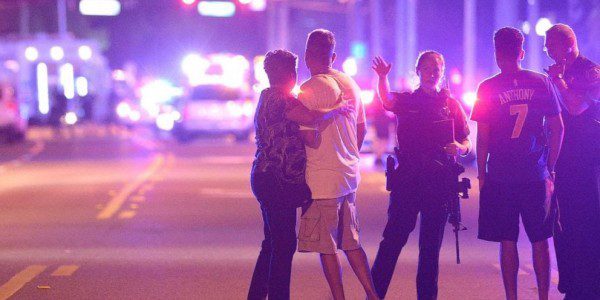

Here in the United States we are witnessing a bubbling over of racist anger, racially motivated violence, and what appears to be a vigorous assertion of white supremacy tied to nationalist fervor. Large segments of the U.S. population seem to be moving past what Duncan Forrester calls “polite and insidious racism” to impolite, aggressive expressions of racist and religious hostility.

I’ve seen people on social media blame Obama for the new racist conflicts in the U.S. That’s laughable, if it weren’t so sad. A better explanation for the rise of hostility is that the cultural cover is being taken off. We felt the heat before. But now we can see the fire.

I recently came across an article by Forrester, in which he reflects on the problems of racism and sectarianism (especially in his context of Great Britain). He asks whether religion is “the problem or the solution?”

Forrester doesn’t land firmly on one side or the other (who can really know for sure?). But he’s honest about the failings of religion and its contribution to sectarianism, racism, and violence. He offers a challenge to religious leaders; one that feels perhaps all the more pressing now, just 11 years after his article was published:

“We have just enough religion to make us hate, but not enough to make us love one one another,” wrote [Jonathan] Swift (1). Sectarianism and racism are destructive ways of dealing with differences. And the churches and other faith groups have a huge responsibility for encouraging or allowing the growth of sectarianism, which is in contrast to the deeper insights of Christian and other faiths.

But the churches have also shown themselves capable, here and there, of responding vigorously and effectively to the challenges of sectarianism and racism by presenting a working model of a community which celebrates difference and cultivates charity. “Time and again we have been reminded,” writes Jonathan Sacks, “that religion is not what the European Enlightenment thought it would become: mute, marginal, and mild. It is fire -and like fire it warms but it also burns” (2). Those who tend this fire have the responsibility for ensuring that it enlightens and warms rather than destroying and consigning to the flames (3).

This is a good word; one that impresses upon me the possibilities of religion as a force for good, when it focuses on the right things: love, mercy, healing, goodness, forgiveness, reconciliation, and repentance.

When religion is about making friends rather than stirring up enemies, when it is about bringing healing rather than harm, when it brings a message of hope rather than of despair and darkness, when it proclaims a gospel of salvation rather than of devastation, then the fire of religion warms rather than burns.

May it be so.

For more posts and discussions on theology and society, like/follow Unsystematic Theology on Facebook

(1) Jonathan Swift, Thoughts on Various Subjects, 1711

(2) Jonathan Sacks, The Dignity of Difference (2002), p. 11.

(3) Duncan Forrester, “Beyond Racism and Sectarianism: Is Religion the Problem or the Solution?” Modern Believing, 2004, p. 20.