I went for a run yesterday in north Minnesota by one of its thousand-plus lakes; it was a fine occasion for my debut hearing of the Avett Brothers new album, True Sadness.

“Spirituality plays a major role in some of your songs. How much do you talk about it within the band?”

Scott Avett answers:

“Constantly. Constantly. Constantly. We talk about spirituality, politics, sports—but mostly politics and spirituality. Seth is always laughing about how we’ll play a barn burner of a show and Bob and I will stay up for two or three hours just talking about Blaise Pascal or Tolstoy writings. It goes a lot of places.”

As a long-time fan of their music, this didn’t surprise me. Their intellectual depth and religious background shines through their lyrics and music. Their art reflects the experiences of life (a mix of the trivial and the tragic) through the lens of that deep reflective prism. As I ran along the trail—I couldn’t help thinking that the most genuinely spiritual experiences I’ve had in many, many years have had nothing to do with “church.”

They’ve happened quite apart from the confines of the institutions of Christianity. They’ve often happened through solitary experiences with music, or art, or contact with the beauty of nature. But I do think it fascinating that whereas, in the “old days,” people used to scratch their spiritual itch in church and by hearing lengthy, meaty sermons and singing hymns with rich theological content, they can get plenty of spirituality—yes by reading Tolstoy or Pascal—but more likely and more often by consuming music or film or thoughtful podcasts.

Not that (and probably you, too) haven’t had uplifting spiritual experiences in church. And not that I haven’t gained a lot from good sermons and theological reflection in community. But real, honest-to-goodness soul-stirring spirituality? Not in “church.” Not much lately, anyway. Give me a Rick Rubin produced Avett Brothers’ album, God’s beautiful green earth, and some substantive theology, and I’m good to go for awhile.

But church (healthy ones, anyway) offer what consumable art or media cannot offer in the same way: community, relationships, accountability, friendships—as covenanted people gather around shared or overlapping visions of the holy and a mutual longing for the divine.

Diana Butler Bass’s Christianity After Religion stands out to me as one of the most important works in the last decade on the development of Christianity, religion, and spirituality. She’s placed an accurate finger on so much of the transformation of attitudes and practices—most of which have created unique, ongoing challenges for the Christian church in the U.S.

Yes, we’ll always have institutional religion. But its undergoing a paradigm shift and the shape of it is changing all the time—for better or for worse. People are still religious, but the way they are religious is different than it used to be. There are the “spiritual but not religious,” folks, but there are also the “religious and spiritual folk.” People now want to be both religious and spiritual. This creates both a challenge and an opportunity for Christian pastors, leaders, theologians. As she writes,

What the world needs is better religion, new forms of old faiths, religion reborn on the basis of deep spiritual connection—these things need to be explored instead of ditching religion completely. We need religion imbued with the spirit of shared humanity and hope, not religions that divide and further fracture the future. (96)

She refers to Wilfred Cantwell Smith’s 1962 book The Meaning and End of Religion, in which he distinguished between the modern term, “religious” and religio, its Latin root. Religion (the modernist form) is often about propositions, certainty, and exclusion (us versus them). Religio, on the other hand, appreciates mystery, seeks after truth and harmony with others, and longs for the holy. It is immersive and subjectively oriented, not primarily doctrinal and objectively oriented. She summarizes:

People intuit that the modern conceptualization of religion as an ideology or institution is bankrupt and has already, in some significant ways, failed. The world cannot afford the sort of religion that we have had for the last two or three centuries. People are searching for something new. That something new, as Wilfred Cantwell Smith said a half century ago, is actually something quite old: faith, the profoundly personal response to “the terror and splendor and living concern of God… Religio is never satisfied with old answers, codified dogmas, institutionalized practices, or invested power. Religio invites every generation to experience God—to return to the basic questions of believing, behaving, and belonging—and explore each anew with an open heart.” (99)

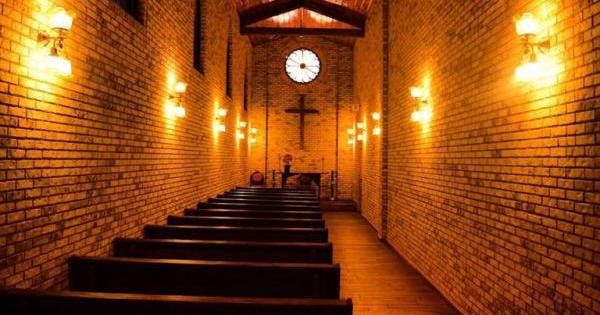

Count me in as one of the spiritual and religious—in the sense of religio. I desire to seek after the mystery, to follow after God, and to do so without rejecting institutional forms of Christianity. But I join with the growing throng that hopes to reinvigorate those institutions, from the inside out. I long for spirituality on runs in the North Woods with the Avett Brothers in my earbuds, but I also long for deeper experiences in church—whether the building is a traditional church, a school auditorium, a movie theater, a backroom in a pub, or a house.

I want to be spiritual and religious. I want my spirituality to exceed my religion, but I want my religion to be spiritual, too. I want it to be religio. “Christianity after religion,” or if you prefer, Christianity in the “post-secular age,” is undergoing a paradigm shift. But whatever new expressions come out of the pressure cooker of change will, I hope, create some new and deeper life.

Rather than responding as too many churches have responded: bowing to the lowest common denominator, making things a bit more superficial with the rush to be practical and “relevant,” why not push in the direction of more meaning, more mystery, and more truth? Not truth primarily in the sense of propositional content or even correct doctrine, but truth in the sense of a deeper, more vulnerable life and death. Truth, like “true sadness,” but also “true happiness.”

This post is part of a Patheos symposium on “Nontraditional Church: Trends for the Future” sponsored by Regal Theatre Church.