Here’s Molly Worthen, writing about the conflict over biblical authority, and in particular the doctrine of inerrancy, during the intramural skirmishes in the evangelicalism of the 1970s:

The problem was this: The doctrine of inerrancy was a comforting gauze that concealed a great deal of ugliness. It disguised the compromise and confusion that are unavoidable when moderns try to live by an ancient and often obscure text.

The doctrine of inerrancy had always been, in its essence a means of managing the Bible’s vulnerability to subjective judgment. Most inerrantists were not naive about either the necessity or the peril of submitting those “God-breathed” words to mortal interpretation. The problem was not interpretation per se, but the presuppositions that so often lay beneath. Inerrancy provided a trump card to play whenever those presuppositions became threatening–a way of asserting that the only appropriate tools for interpreting a problematic verse were other verses in the same text, and that revelation itself provided evidence of its own perfect authority.

I would add, though, that evangelical inerrantists have no problem utilizing tools outside of the text itself (archeology, etymologies, comparative literature, etc.) whenever those tools serve to confirm their evagnelical conservative presuppositions about what the text meant, and means (the “plain meaning –plain to them). She goes on to say that,

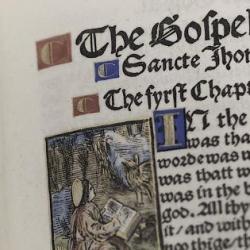

The doctrine was meant to protect the Reformers’ problamation of sola scriptura from the presumptions of human reason, subjective experience, or hubristic tradition. British theologian J. I. Packer dated the origins of Reformation heroes Martin Luther and Huldrych Zwingli, if not to their fourteenth-century predecessor John Wycliffe. Packer was an irenic inerrantist who urged charity in the debate, but he made plain what was at stake: “As soon as you convict Scripture of making the smallest mistakes you start to abandon both the biblical understanding of biblical inspiration and also the systematic functioning of the Bible as the organ of God’s authority, his rightful and effective rule over his people’s faith and life.”

Having recently spent a bit of time in Luther’s writings on the gospel and the Bible, I have to also add here that Luther was no evangelical — certainly not in his view of biblical authority, the canon, etc. Inerrantists are averse to any “canon within a canon” approach, and Luther made clear that he operated on this basis. He was an early critical reader of Scripture (even rejecting James as non-canonical on the basis of perceived theological incoherence with Paul); he was not an uncritical inerrantist operating with a “flat” or uniform view of the Bible’s authority.

In any case, Worthen goes on to point out that,

Anyone who looked around at modern life quickly observed that this rightful rule was teetering. Those evangelicals who questioned inerrancy had to come to terms with other sources of authority that could somehow help modern Christians follow the gospel into the twenty-first century.

She rightly points out we can’t understand the emergence of evangelicalism during this era exclusively through the larger culture war and the rise of the Christian right as a fight against secular liberalism. It was both energized and fractured by its own internal struggles over the question over authority, in particular what the Bible is and how it functions as authority in the contemporary world.

The “comforting gauze” analogy works to help explain how the doctrine of inerrancy functioned. But we need other metaphors, too. It wasn’t just a gauze to cover over the “pain” and “ugliness’ of ambiguities and uncertainties in the Bible itself. It was also an ideological and political weapon wielded to created more pain and ugliness: to determine who was in and out, whose views counted and who didn’t, who could keep their jobs and who couldn’t.

The fundamentalists won that battle but, in light of the state of evangelicalism today, you have to wonder if winning that battle also meant losing the war.