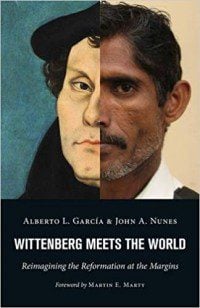

If you’ve been following my blog in the past few weeks, you know I’ve been doing a lot of reading on Luther’s theology. Recently I picked up what looks to be an inspiring and timely book, Wittenberg Meets the World: Reimagining the Reformation at the Margins, by Alberto L. Garcia and John A. Nunes.

The book offers something unique in Luther scholarship: it explores the theology of Luther and the impulses of the Reformation from the perspective of the “margins”–minority but emerging voices in Lutheran scholarship and theologies informed by Luther’s writings.

But there’s a caveat: The verbiage of “minority” is misleading, because the truth is that, just like with  Christianity broadly, Lutheranism is growing rapidly in countries outside North America and Europe, while it’s on a precipitous decline in western countries.

Christianity broadly, Lutheranism is growing rapidly in countries outside North America and Europe, while it’s on a precipitous decline in western countries.

Martin Marty points out in the book’s foreword that there are “more Lutherans in Ethiopia (6.3 million), Tanzania (5.8 million), and Indonesia (5.8 million) that in any other nation except Germany and Sweden.” And that includes the U.S., which has over 4 million Lutherans.

In the introduction, the authors offer a good definition or description of “postcolonial theologizing”:

A key component of our postcolonial theologizing is that we are suspicious of the use of correct and proper premises for the sake of enslaving the strange communities of with idolatries of power. We have learned through our theological inquiries from the margins that Luther was also suspicious of the use of theological premises and reason when they were employed to enslave people of faith. Postcolonial thinking wakes us from our slumbers of theological and rational idolatrous certainty. This does not mean that we are relativists in terms of theological constructions. What it means is that our starting point for doing theology is our historical borderland location. It is not by our thinking that we become genuine Christian theologians.

And then,

Postcolonial thinking subverts the Cartesian dictum, “I think, therefore I am.” Postcolonial thinking affirms first and foremost “I am where I think.” Our universal thinking begins with this particular “I am.” We are also cognizant that our communities of faith understand this “I am” as communal. There is no identity or theologizing apart from our communities of faith. This identity is marked and shaped by a life under the cross. In the words of Luther: “For one becomes a theologian by living, by dying, by being damned: not by mere intellectualizing, reading, and speculating.” This life at the borderlands involves a certain risk and vulnerability because we are forced to hear other voices in their contexts and need, rather than listen only to our theological cliches or the sounds of our human righteousness. (xvi)

Some of you are rightly thinking, “But Luther didn’t always heed this advice!” (most infamously. in his approach to the Peasant revolt and in his racist, anti-Semitic comments). I’m interested to see if and how the authors deal with the negative example of Luther in their engagement with Luther’s thought from the “margins.”