You decide to pick up that coffee cup and take a sip. Was that decision really free, or was it the determined outcome of unconscious brain activity that led to your picking up that cup and sipping the good, dark stuff?

Or, the crime you committed (or were about to commit: See Minority Report) was determined by something other than your conscious, willful choice, are you really responsible for it?

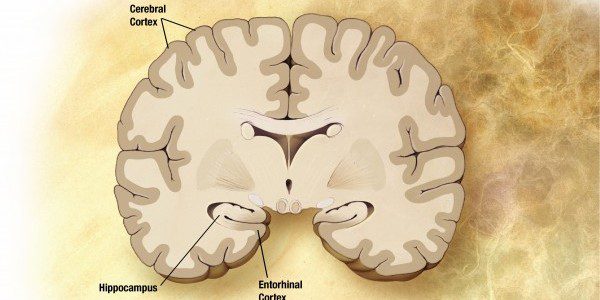

Some scientists (and philosophers) say that the feeling of having free will to make any number of decisions that we make each day is just that: subjective feeling. We operate with an intuition that we’re both free and responsible for our choices, but in truth, our brains, our genes, and any number of influences (conscious and non-conscious) on the makeup and activity of our brains determines our thoughts, feelings, and behaviors.

There’s no such thing as a conscious “free will” that penetrates through the murky mass of all those predetermining influences, giving us the power to make real choices that haven’t already been set in motion by those influences and by the internal preparatory activity of our brains, all of which leads up to the particular choices we make.

Christian Jarrett explains, in an essay from last Feb., how and why free will has taken a hit, due to research in the neurosciences:

Back in the 1980s, the American scientist Benjamin Libet made a surprising discovery that appeared to rock the foundations of what it means to be human. He recorded people’s brain waves as they made spontaneous finger movements while looking at a clock, with the participants telling researchers the time at which they decided to waggle their fingers. Libet’s revolutionary finding was that the timing of these conscious decisions was consistently preceded by several hundred milliseconds of background preparatory brain activity (known technically as “the readiness potential”).

The implication was that the decision to move was made nonconsciously, and that the subjective feeling of having made this decision is tagged on afterward. In other words, the results implied that free will as we know it is an illusion — after all, how can our conscious decisions be truly free if they come after the brain has already started preparing for them?

A recent article in the Atlantic by Stephen Cave takes up this development, based on Libet’s research, and explores the potential (and possibly troubling) implications for the scientific debunking of free will.

As theologians and philosophers have long known, if we deny the reality of free will, we may also abdicate a genuine sense of responsibility and culpability. If, according to science, free will is a mirage, an illusion, how will that play out on the witness stand? How will judges and jurors be instructed to rule in accordance with this understanding of human nature?

Maybe “the devil made me do it,” won’t hold any sway, but what about “my brain made me do it”? “I had no real choice in the matter…my action, howsoever heinous, was determined by background brain activity–quite apart from my conscious control?”

On the plus side, Cave points out, there may be some benefits to disabusing ourselves of the notion of free will. Referring to Sam Harris, Cave suggests that this recognition may give us more empathy for criminals, psychopaths, and even–yes–terrorists. It may stir us to explore the root causes of violent behavior and inspire us to explore more scientific approaches to rehabilitation–rather than lashing out in anger and taking the usual vindictive responses to violence.

Nonetheless, the gist of Cave’s essay, boldly titled, “There’s No Such Thing as Free Will: But We’re Better Off Believing in it Anyway,” is that the scientific debunking of free will would have more negative consequences for society than positive–were it to become widely known. It’s well-established (as Cave points out) that when people believe their actions are determined, outside of their conscious control, they are more apt to behave deceptively (to steal, to lie, to cheat, etc.) than if they believe they are free and responsible for their choices.

But if the illusory nature of free will is better off kept a secret, one wonders why Cave decided to write this article and publish it in a popular magazine, in the first place?

But there’s a bigger, more important criticism to be raised: Cave ignores recent counter-evidence to the Libet study and to its presumed implications.

In the Jarrett essay I referenced earlier, he refers to two recent studies–from two teams of German and French neuroscientists–which show that the Libet study should not be taken as science’s final word on free will.

These studies both show that we have the capacity to consciously “veto” that preparatory brain activity that Libet showed operates behind the scenes of our decisions. According to the lead researcher of one of the studies,

“A person’s decisions are not at the mercy of unconscious and early brain waves,” the lead researcher, Dr. John-Dylan Haynes of Charité – Universitätsmedizin in Berlin, said in the study’s press release. “They are able to actively intervene in the decision-making process and interrupt a movement. Previously people have used the preparatory brain signals to argue against free will. Our study now shows that the freedom is much less limited than previously thought.”

These researches concluded that the background, preparatory brain activity may be more random than Libet’s study suggested (not necessarily causally linked to subjective decisions made afterward)–and while it leads to quicker decisions being made, when those conscious decisions match up with that random activity, it can be reversed by the agency of the person making real choices in real time.

…these neuroscientists say the new picture is much more in keeping with our intuitive sense of our free will.

It’s surprising that Cave did not include these studies in his article. At the very least, they complicate his thesis that science “has dealt a further blow to the idea of free will.”

We’re probably not as free as we often feel we are. Still, we don’t need (at this point) to conclude that free will is just an illusion.