The Word and the Spirit in creation,

Reveal the love of Divine Sophia for us.

Participation in the divine life, our destination:

Once we take on the savior’s poultice.

In Jesus and Mary, the Word and Spirit,

Accomplish the plans of Divine Sophia.

They are an inseparable doublet,

And prove the truth of the filioque.

“For he has made known to us in all wisdom and insight the mystery of his will, according to his purpose which he set forth in Christ as a plan for the fulness of time, to unite all things in him, things in heaven and things on earth” (Eph 1:9-10 RSV).

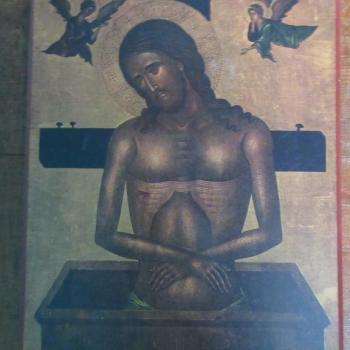

In the incarnation, we find Divine Sophia united with created Sophia, the two becoming one, so that creation could attain its proper place in eternity. Created Sophia’s desire for a cosmic mediator has been fulfilled: one of the Trinity has become incarnate, accomplishing in himself what created Sophia and Divine Sophia alike had planned for humanity:

With us and through us he encompasses the whole creation through its intermediaries and the extremities through their own parts. He binds about himself each with the other, tightly and indissolubly, paradise and the inhabited world, heaven and earth, things sensible and things intelligible, since he possess like us sense and soul and mind, by which, as parts, he assimilates himself by each of the extremities to what is universally akin to each in the previously mentioned manner. Thus he divinely recapitulates the universe in himself, showing that the whole creation exists as one, like another human being, completed by gathering together of its parts one with another in itself, and inclined towards itself by the whole of its existence, in accordance with the one, simple, undifferentiated and indifferent idea of production from nothing, in accordance with which the whole of creation admits of one and the same undiscriminated logos, as having not been before it is.[1]

The incarnation, planned from the foundation of the world, occurred at the time and place established by Divine Sophia. Created Sophia had worked with the Holy Spirit to lift up holy men and women and to then posit them before God, to see God’s reaction. It was only when presented with the Theotokos that Divine Wisdom found in humanity the one whom had been sought so that the incarnation could take place. Divine Sophia sent the angel Gabriel to her, to tell her that she had been chosen to have a special child, the God-man. She had been given the chance to reject this role, but her love for God was such that she freely accepted it; “since Mary was very pure she received him.”[2] Her yes was to become the voice of humanity; when she had been asked whether or not humanity would accept its place in the divine plan, her yes served also to indicate that humanity itself would humble itself to God:

The answer of the Most Holy Mother of God manifested the very same creaturely freedom that, in the person of Even and then Adam, defined itself against God’s will. But now, in the person of the Most Holy Mother of God, the creature realizes its freedom not in willfulness but in the obedience of love and self-renunciation. Divine Maternity is the human side of the Incarnation; it is the condition without which the Incarnation could not have been accomplished. Heaven could not have come down to the earth if the earth had not received heaven. The Most Holy Virgin Mary is therefore the eternally foreseen and preestablished center of the creaturely world.[3]

She loved God, and it was this love which made her great; it gave her humility and made her beautiful to behold – not just to us, but to God: “Even God loves beauty which is from the will.”[4]

While Divine Sophia had planned the incarnation for the sake of the deification of creation, the fall of Adam meant that the incarnation also had to overcome the fault of Adam, to heal human nature and overcome the effects of fall. Created Sophia had worked with the graces she had been given, and had raised many holy men and women in advance of the incarnation itself. While worthy of honor and respect, their holiness was not capable of healing human nature: they could not cure humanity from the stain of original sin (and so, likewise, they could not deify it). It was to be the God-man, Jesus, in his life and death that the causality established by original sin was to be overcome; that is, in him, the law of causality itself would be overturned. Humanity in its self-centered search for pleasure had abandoned God; closing itself off from the grace, humanity established the rule of death. Jesus, in the incarnation, took on death, took it and transformed it, as St Maximus the Confessor said:

In His love He deliberately accepted the painful death which, because of pleasure, terminates human life, so that by suffering unjustly He might abolish the pleasure-provoked and unjust origin by which this life is dominated. For, unlike that of everyone else, the Lord’s death was not the payment of a debt incurred because of pleasure, but was on the contrary a challenge thrown down to pleasure; and so through this death He utterly destroys that justly deserved death which ends human life.[5]

Humanity had, in its special way, been made in the image of God – it was, as has already been said, made in the image of created Sophia. While the fall of humanity meant that this image had been blemished, so that humanity had to be restored to its original integrity, we must understand that the incarnation was always planned: it was not due to human sin. It was always the intention of Divine Wisdom:

The Incarnation is God’s conclusion to His own premise in the human, His image. This is why in the Atonement it is not so much a matter of making amends for human nature as it is of human nature being restored. The Word leaves “the peaceful silence” to establish a deifying communion. The Word becomes incarnate in the initial, original nature (the miraculous birth) and fulfills it conclusively: in Him, Paradise already matures into the Kingdom: “The Kingdom of God has come near” (Lk. 10:11).[6]

The incarnation was, to be sure, an act of profound love for humanity (and the rest of creation). The Word of God, the second Person of the Godhead, took on human flesh and became present in world history – and it was done in a manner so that he took into consideration humanity’s fallen mode of being. Since humanity had become preoccupied with itself, it was therefore fitting that the Word became human so that we can look upon him and have our gaze, through him, once again turned towards God:

For men’s mind having finally fallen to things of sense, the Word disguised Himself by appearing in a body, that He might, as Man, transfer men to Himself, and centre their senses on Himself, and, men seeing Him thenceforth as Man, persuade them by the works He did that He is not Man only, but also God, and the Word and Wisdom of the true God.[7]

The incarnation, therefore, redirects our lives, not by rejecting who we are, but by employing the fullness of our being, showing the positive value of material creation. The incarnation utterly rejects the so-called Gnostic separation of the eschaton from the world, but rather, shows that the world is to be lifted up into the eschaton because the eschaton has been immanentized:

And the Son of God deigns to become and to be called Son of Man; not changing what He was (for It is unchangeable); but assuming what He was not (for He is full of love to man), that the Incomprehensible might be comprehended, conversing with us through the mediation of the Flesh as through a veil; since it was not possible for that nature which is subject to birth and decay to endure His unveiled Godhead. Therefore the Unmingled is mingled; and not only is God mingled with birth and Spirit with flesh, and the Eternal with time, and the Uncircumscribed with measure; but also Generation with Virginity, and dishonour with Him who is higher than all honour; He who is impassible with Suffering, and the Immortal with the corruptible.[8]

The work of the incarnation is cosmic; by overcoming the gap between God and creation, the incarnation allows for the unity of the two. The heavens and the earth are no longer the same; the two have become united. Through the Logos, humanity has accomplished its role in creation; through the Logos, everything has been brought together, for, as we just said, the eschaton has been immanentized:

For the wisdom and sagacity of God the Father is the Lord Jesus Christ, who holds together the universals of being by the power of wisdom, and embraces their complementary parts by the sagacity of understanding, since by nature he is the fashioner and provider of all, and through himself draws into one what is divided, and abolishes war between beings, and binds everything into peaceful friendship and undivided harmony, both what is in heaven and what is on earth (Col. 1:20), as the divine Apostle says.[9]

In the incarnation, the divine hypostasis of the Logos, God the Son, assumed human flesh and made it his own in the person of Jesus Christ. Orthodox theology makes it clear that we speak of one person who has two natures:

It is thus that he had in himself, wholly and completely, the created, circumscribed, and passable human essence, which was predicated of him in the same way that the divine nature was predicated of him. Since the two natures came together in him and together were predicated of him, along with all their natural properties, for this reason they are said to be united with one another in him, without change, without mixture, without variation – and this, because the two natures were united in one and the same hypostasis of the eternal Son.[10]

While we can make some sense out of this, there is, to be sure, the question of how this can be. It is easy to assume the answer is one of divine fiat: God can do what God wants. But there is something improper about this response. God works according to Sophia, according to the Divine Nature, and does not contradict it. God’s omnipotence must be understood in relation to God’s character, which is love. Divine Sophia reveals herself through the three persons of the Trinity in love, and works in creation to allow creation its freedom. Describing the incarnation in the line of a divine fiat ignores the freedom of creation. Rather, as we have said, Divine Sophia worked with and supplemented the work of created Sophia: the Logos did not incarnate himself as some divine force imposing itself upon created Sophia, but rather, as the fitting response to created Sophia’s love. The love of Divine Sophia for created Sophia is joined by created Sophia’s love for Divinity. It is in the bond of love established between Divine Sophia and created Sophia that allows for and generates the hypostatic union:

Nothing sequent to God is more precious for being endowed with intellect, or rather is more dear to God, than perfect love; for love unites those who have been divided and is able to create a single identity of will and purpose, free from faction, among many or among all; for the property of love is to produce a single will and purpose in those who seek what pertains to it.[11]

The Logos assumed human nature, something which is same for all humanity, allowing humanity therefore to be united in Christ. “The humanity of Christ is not other than [the humanity] of each man – past, present, or future. Rather, it is humanity but as not other. And so, we see how it is that our nature, which is not other than Christ, is, in Christ, most perfect.”[12] Humanity, divided against itself, warring against itself, is capable returning to its integral unity in Christ. This potential comes from the assumption of human nature in the incarnation; its actuality is activated by love:

Since token of such great love toward us has been shown, we are moved to and kindled with, love of God, who has done so much for us; in this way, we are justified, that is, we are released from our sins, and so we are made just. Indeed, Christ’s death justifies us, as by it charity is kindled in our hearts.[13]

While this does help, certainly there is more that needs to be said. While love helps tie together that which was separated, so that divided humanity can reestablish its original and essential unity, it is still difficult to understand how this works in the hypostatic union. There is, to be sure, an element of divine mystery involved, and no discussion on the hypostatic union can be had without acknowledging this – the fact that the Word has chosen humanity and has become one of us is, in part, the personal prerogative of the Word. Nonetheless, again, there has to be something fitting about it: the divine persons do not act erratically, especially the Logos. Sophiology offers us another, complementary explanation for the incarnation, as to its fittingness, and why it should not just be seen as an act of force. It is because of the way humanity, in its nature, is a derivate form of Divine Sophia, and so, in its core, it reflects and therefore points to Divine Sophia. And since humanity points to Divine Sophia, it is capable of being a receptacle for Divine Sophia, to have the Logos incarnate and assume human nature. “The Incarnation thus appears to postulate on its hypostatic side at least, some original analogy between divine and human personality, which yet does not overthrow all the essential difference between them. And this is found in the relation between type and prototype.”[14] The analogy of being which connects human-Sophia and Divine Sophia, and allows for the Chalcedonian definition to resist the rationalistic criticism often given to it.[15]

Because humanity points Divine Sophia, it reveals something of Divine Sophia to itself and to the rest of creation. This is a foundation for the incarnation. For the Logos (as with the Holy Spirit) is revealing the glory of the Father, Divine Sophia, to the world. The Son, because of his nature to be begotten, is the one who incarnates himself:

The Logos is the demiurgic hypostasis whose face is imprinted in the Divine world, as in the Divine Sophia, by the self-revelation of Divinity through the Logos. The hypostasis of the Logos is directly connected with Sophia. In this sense the Logos is Sophia as the self-revelation of Divinity; He is her direct (although not sole) hypostasis. The Logos is Sophia in the sense that He has Sophia as His proper content and life, for in Divinity, Sophia is not only the totality of ideal and nonliving images but also the organism of living and intelligent essences that manifest in themselves the life of Divinity. Sophia is also the heavenly humanity as the proto-image of the creaturely humanity; inasmuch as she is etnerally hypostasized in the Logos, she is His pre-eternal Divine-Humanity.[16]

The Spirit, as the one who gives life, also makes an appearance in the world in and through the Theotokos, in whom the Spirit fills for the sake of the incarnation.[17] The Word and the Spirit work together in the incarnation, continue their revealing work according to their personal character: the Word, revealing the Father through all ages, also reveals the Father in and through his sophianic humanity:

From the God-human shines forth very God in his Glory, in the light of everlasting Godhead, divine Wisdom. In him, indeed, for the first time the true idea of Divine-humanity, according to the conception of the Creator, is realized in its integrity, in the unshadowed clarity of its form. For Divine-humanity is the unity and complete concord of the divine and created Wisdom, of God and his creation, in the person of the Word.[18]

However, the fact that the Spirit is seen in and through the Theotokos reveals the sophianic character of the Most Holy Virgin: “Already she, who begot Wisdom itself in the flesh, has imitated Wisdom in her own being…”[19] Though the spirit is not incarnate in her, the spirit is revealed through her – Mary is the human revelation of the Spirit, always beside her Son the same way the Spirit is always together with the Son. The femininity of the Spirit in Semitic languages reflects the way the Theotokos reveals the Spirit.[20] Mary, in her kenotic humility, is completely open to the Spirit and is the Spirit’s perfect vessel and the person who represents the Spirit to the world. Her work is completely tied to the work of Christ, as the Spirit is tied to the Logos. She reveals Divine Motherhood, the eternal feminine. Genesis tells us that the image of God in humanity is twofold: in the masculine (Adam and New Adam) and in the feminine (Eve and the New Eve).[21] Mary, by her complete openness to the Spirit, reveals Sophia and Divine Motherhood:

The Mother of God is the personal manifestation of Divine Wisdom, Sophia, which in another sense is Christ, the power of God and the wisdom of God. In this way there are two personal images of Sophia: the creaturely and the divine humanly, and two human images in the heavens: the Godman and the Mother of God. This must be understood in connection with the doctrine of the Most Holy Trinity, of God and the world. The Divine image in humankind is disclosed and realized in the heavens as the image of two: of Christ and of His Mother. The Son of God contains in himself the whole fullness of Divinity proper to the whole Most Holy Trinity, one in essence and undivided. And as the New Adam, having been incarnated and made human, the Son of God is the pre-eternal Human, who imagined himself in Adam. Only on the basis of this ontological affinity with the image and prototype are the incarnation and the hominization of the Second Hypostasis possible. The human image as the Divine image and the Divine image as the human image are glorified in both the first and second Adam. And yet in the heavens there is still one human image which obviously pertains to the fullness of the human prototype, namely, the Mother of God, “the second Eve.”[22]

The Theotokos, as the one who answers yes to God for humanity, is completely sophianic in her being.[23] She is completely open to the work of God in and through her, allowing her to have such an important place, not only in salvation history, but eternity:

Heaven is his throne and Mary his Mother and behold they are not equal,

for the throne does not resemble the Mother because the Mother is greater.[24]

It is also in this fashion we can understand the Theotokos as co-redemptrix; her purity and openness to God was the precondition for the incarnation; in her, all creation rejoices, for in her the seeds of Divine Wisdom have found their proper home in creation, allowing the fruit of her womb to be the incarnation of the Divine Logos:

What other creature could ever be purer than she, or equal to her in purity, or anywhere near as pure? For this reason, she alone of all mankind throughout the ages was initiated into the highest mysteries by these divine visions, was united in this way with God, and became like Him. She then accomplished the super-human role of intercessor on our behalf, and brought it to perfection through herself, not just acquiring the exaltation of mind that lies beyond reason, but using it for the sake of us all, and achieving this great and surpassingly great deed by means of her boldness towards God. For she did not merely come to resemble God, but she also made God in the likeness of man, not just by persuading Him, but by conceiving Him without seed and bearing Him in a way past telling.[25]

Through the incarnation, humanity is united to God in the New Adam, in bonds of love; humanity becomes the realization of creaturely Sophia, able to mediate the graces of God into the world as priest and raise it up in theosis, even as it had been deified. “Mankind reunited to God in the Blessed Virgin, in Christ and in the Church is the realisation of the essential Wisdom or absolute substance of God, its created form or incarnation.” [26] Divine Sophia is united to creaturely Sophia through the Theotokos, for she had opened herself to the Spirit and works as the Spirit-bearing Mother of God. Her work is in time, but as with all great metaphysical events, it is an act in eternity. “Mary became the Mother of God in time, because the whole existence of the human race flows in time. But this divine motherhood which was initiated in time, and is foreordained from the ages, has already an eternal nature, is accomplished for all times and for eternity.”[27] And, because Divine Sophia sees the Theotokos in eternity, the world is seen as good and humanity is, despite the fall of Adam, justified:

It was in the contemplation of His eternal thought of the Blessed Virgin, of Christ and of the Church that God gave His absolute approval to the whole Creation when he pronounced it to be tob meod, valde bona. There was the proper subject for the great joy which the divine Wisdom experienced at the thought of the sons of Man; she saw there was the one pure and immaculate daughter of Adam, she saw there the Son of Man par excellence, the Righteous One, and lastly she saw there the multitude of mankind made one under the form of a unique Society founded upon love and truth. She contemplated under this form her future incarnation and, in the children of Adam, her own children; and she rejoiced in seeing that they justified the scheme of Creation which she offered to God: et justificata est Sapientia a filiis suis (Matt. Xi. 19).[28]

Because she completely reveals the Spirit, in the same way as Christ is the revelation of the Word, the revelation of Divine Sophia is through the two, Mary and Christ, together.[29] “It is impossible to venerate the Son in separation from His Mother, to adore the Divine Infant in isolation from the Mother of God.”[30] And so, as there can be no proper Christian worship which is not a worship of the Trinity, there can be no Christianity without the Theotokos. But her role must always be as she herself said: as the handmaid of the Lord, as the one who does as God wills. Mary, though the height of creation, must still be seen for who she is, and why, though her work in cooperation with the Spirit makes her co-redemptrix, secondary to the Son. Her work, her very being, is to magnify the work of her Son: the things done in the history of Israel, which has led to the Lord’s great accomplishment in Mary, leads her to humbly, and therefore greatly, point to her Son.[31]

She became a letter, and what was written on her is the Word;

when it was read, the earth was enlightened by its tidings.[32]

It is the work, life, death and resurrection of her Son, Jesus the incarnate Word, which we must turn to next.

[1] St Maximus the Confessor, “Difficulty 41” in Maximus the Confessor. Trans. and intr. Andrew Louth (London: Routledge, 1996), 160.

[2] Jacob of Serug, “Homily on the Blessed Virgin Mother of God, Mary” in On the Mother of God. Trans. Mary Hansbury (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 21.

[3] Sergius Bulgakov, The Lamb of God, 179.

[4] Jacob of Serug, “Homily on the Blessed Virgin Mother of God, Mary,” 25.

[5] St Maximus the Confessor, “Fourth Century of Various Texts” in The Philokalia: The Complete Text. Volume Two. Trans, G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber, 1990), 245.

[6] Paul Evdokimov, Woman and the Salvation of the World. trans. Anthony Gythiel (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1994), 68.

[7] St Athanasius, On the Incarnation of the Word in NPNF2(4):44-45.

[8] St Gregory Nazianzen, “Oration on the Holy Lights” in NPNF2(7): 356-7.

[9] St Maximus the Confessor, “Difficulty 41”, 161-2.

[10] Theodore Abū Qurrah, “Discerning the True Religion” in Theodore Abū Qurrah. Trans. John C. Lamoreaux (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 2003), 107-8.

[11] St Maximus the Confessor, “First Century of Various Texts” in The Philokalia: The Complete Text. Volume Two. Trans, G.E.H. Palmer, Philip Sherrard and Kallistos Ware (London: Faber and Faber, 1990), 174.

[12] Nicholas of Cusa, “Dies Sanctificatus” in Nicholas of Cusa’s Early Sermons: 1430 – 1441. trans. Jasper Hopkins (Loveland, CO: The Arthur J. Banning Press, 2003), 370.

[13] Peter Lombard, The Senteces Book 3: On the Incarnation of the Word. Trans. Giulio Silano (Toronto: PIMS, 2008),78.

[14] Sergei Bulgakov, Sophia: The Wisdom of God. trans. Rev. Patrick Thompson, the Rev. O. Fielding Clarke and Miss Xenia Braikevitc (Hudson, NY: Lindisfarne Press, 1993), 85-6.

[15] See ibid., 88.

[16] Sergius Bulgakov, The Lamb of God, 187.

[17] While each person of the Trinity has their own proper activity, we must remember, the Trinity is always at work together, not apart, and the work of the Son is also a work of the Father and the Spirit . “We know that whenever God the Son is wholly named then the Father is wholly present with the Spirit; that when God the Father is wholly praised the Son is wholly there through the Spirit; and that when the Father is wholly confessed and glorified with the Son, then there too is the whole Spirit.” St Symeon the New Theologian, “The Third Theological Discourse” in St Symeon the New Theologian: The Practical and Theological Chapters & The Three Theological Discourses. trans. Paul McGuckin, CP (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1982), 135. For this concept, see also DZ 281, 429, 704..

The Son is always revealed by the Spirit, and is always at work with the Spirit: the filioque, properly understood, points to the fact that where there is the Spirit, there is the Son, and where there is the Son, there is the Spirit:

When we say “Son,” our thought adds “and the Spirit” and vice versa. This “and” unites the two hypostases in one revelation of the Divine Sophia. Sophia is one, but there are two sophianic hypostases, which reveal one subject, but in a double-manner: uni-dyadically, without separation and without confusion. One hypostasis does not repeat the other, but manifests it: the Word is accomplished by the Holy Spirit and the spirit quickens the Word. Divinity contains the Word and the Spirit reveals Him: “for the Spirit searcheth all things, yea, even the deep things of God” (1 Cor. 2:10). By the Spirit the Father inspires Himself in His own Word, and this self-inspiration is divine life, Beauty. Inspiration is not objectless and empty: it creatively reveals the “deep things of God.” Divine Life is an act of divine self-inspiration, and in this sense a cognitively creative act, in the Word through the Holy Spirit.

Sergius Bulgakov, The Comforter, 183-4.

[18] Sergei Bulgakov, Sophia: The Wisdom of God, 95.

[19] St Andrew of Crete, “On the Dormition of our Most Holy Lady, the Mother of God. Homily I” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. Trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 111.

[20] There is a profound connection between the Holy Spirit, Sophia, the Virgin and the feminine. In Semitic languages, the word “Spirit” has two genders; it can be feminine. The Syriac texts on the Paraclete refer to “she who consoles.” The Gospel of the Hebrews has Christ refer to “my mother, the Holy Spirit.”

Paul Evdokimov, Woman and the Salvation of the World, 219-20.

[21] “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God he created him; male and female he created them “(Gen 1:27 RSV).

[22] Sergius Bulgakov, The Burning Bush, 80.

[23] See Pavel Florensky, The Pillar and Ground of the Truth, 253-4.

[24] Jacob of Serug, “Concerning the Holy Mother of God, Mary, When She Went to Elizabeth to See the Truth Which Was Told to Her by Gabriel,” in On the Mother of God. Trans. Mary Hansbury (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 69.

[25] St Gregory Palamas, The Homilies, 442-3.

[26] Vladimir Solovyev, Russia and the Universal Church, 176.

[27] Sergius Bulgakov, The Burning Bush, 99.

[28] Vladimir Solovyev, Russia and the Universal Church, 176.

[29] See Sergius Bulgakov, The Comforter, 186.

[30] Sergius Bulgakov, The Friend of the Bridegroom, 13.

You are the royal throne, around which angels stand (cf. Is 6:1), to see their Lord and creator seated upon it. You are called the spiritual Eden, holier and more divine than that of old; for in the former Eden the earthly Adam dwelt, but in you the Lord from heaven. The ark prefigured you (cf. Gen 6:14), in that it guarded the seeds of a second world; for you gave birth to Christ, the world’s salvation, who overwhelmed <the flood of> sin and calmed its saves. The burning bush was a portrait of you in advance (cf. Ex 3:2); the tablets written by God described you (cf. Ex 32:15f.); the ark of the law told your story (cf. Ex 25:10); the golden urn (cf. Ex. 16:33) and candelabrum and table (cf. Ex 25:23, 31), the rod of Aaron that had blossomed (cf. Num 17:23) – all clearly were foreshadowings [of you]. For from you issues the flame of divinity, the self-definition and Word of the Father, the sweet heavenly manna, the nameless “name that is above every name” (Phil 2:9), the eternal and inaccessible light, the heavenly “bread of love” (Jn 6:48), the uncultivated fruit that grew bodily to maturity from you.

St John of Damascus, “On the Dormition of the Holy Mother of God. Homily I,” in On the Dormition: Early Patristic Homilies. Trans. Brian E. Daley, S.J. (Crestwood, NY: St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1998), 192.

[32] Jacob of Serug, “Homily Concerning the Holy Mother of God, Mary, When She Went to Elizabeth to See the Truth Which Was Told to Her by Gabriel,” 70.