“Only to man does God listen. Only to man does God manifest Himself. God loves man and, wherever man may be, God too is there. Man alone is counted worthy to worship God. For man’s sake God transforms Himself.”[1]

Creation, all that is good and lovely in it, was made for the sake of humanity.[2] “Men cultivate the earth for themselves; but if they fail to recognize how great is God’s providence, their souls lack all spiritual understanding.”[3]

Scripture tells us that all creation sings the glory of God and that all creation finds itself affected by the saving work of God. How, then, can it be suggested that it is only to man that God manifests himself, only for the sake of humanity that creation was made, and so only to humanity God listens? If we want to understand God’s providential work so as not to lack all spiritual understanding, if we want to understand how God is at work in creation, we need to understand what is being said in these paradoxical passages.

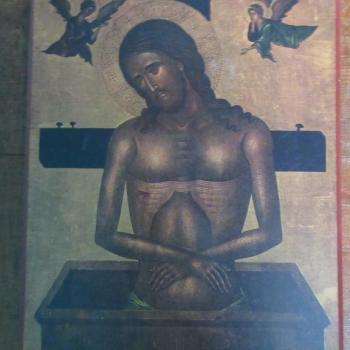

The answer can only be that of the incarnation. It cannot be true if it is any man who is being discussed. The truth can be found only in the new man, the second Adam, Christ the Godman. Creation was made for Godmanhood. Creation was made to be united with and infused with grace, grace which would come through the incarnation of the Logos. As God, the Logos is also man. The Logos assumed human nature, transforming himself, so that he is God and man. Humanity, therefore, has an important role in salvation history; for the sake of the Godman, providence has been at work with humanity. Humanity has a special role in creation because its nature has been chosen as the one the Logos assumed unto himself. In and through the Godman humanity is found worthy of worshiping God, because man, or rather, a man, the Godman Jesus, is worthy. “Worthy is the Lamb who was slain, to receive power and wealth and wisdom and might and honor and glory and blessing!” (Rev. 5:12 RSV).

Since creation was made for Godmanhood, since creation was made for the incarnation, then one can indeed say it was made for the sake of man, for the sake of the Godman, God transforms himself. “Have this mind among yourselves, which was in Christ Jesus, who, though he was in the form of God, did not count equality with God a thing to be grasped, but emptied himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men” (Philip. 2:5-7 RSV). God the Son, the Logos, emptied himself so that humanity can be taken up and become hypostatically united to him in his person. The Logos emptied himself so that he can take up humanity; through humanity, he saves the whole of creation. “Thus, then, does the Word of God in all things hold the primacy, for He is true man and Wonderful Counsellor and God the Mighty, calling man back again into communion with God, that by communion with Him we may have part in incorruptibility.”[4] And it is in and through our communion with God, creation is drawn back toward God, to have communion with God as well. The whole of creation finds the Godman as the centerpiece of God’s providence in history:

God became man in order that man become God: God’s humanization has as a direct consequence the deification of man, gives to man an ontological foundation. Between heaven and earth, between God and man, an eternal ladder was erected after Christ went downward and upward with His flesh as, with Him, did his Most Pure More. After the descent of the Holy Spirit, grace ceaselessly flows into the world, and the world becomes a receptacle of divine powers.[5]

Humanity has become a fixed point in creation because of the Godman. Through the incarnation, humanity has become deified. Now, all of creation rejoices in the revelation of the adopted sons and daughters of God. All of creation rejoices because humanity has taken its role as cosmic mediator; all of creation exists for the sake of humanity because all of creation finds its existence affirmed in humanity. Godmanhood is the teleological end of creation, for Christ is the eschaton made flesh. Creation was made under the direction of God’s providence so that it can reach that teleological goal. Godmanhood puts humanity front and center in creation. Humanity is the pre-established means God has chosen by which creation achieves Godmanhood. Thus, humanity is not just a goal of creation (because Godmanhood includes humanity), but in this nuanced way, we can speak of humanity as the reason for creation. Likewise, if humanity can be seen as the reason for creation, then the rest of creation must, in this sense, be made in order to make sure humanity can exist so that the incarnation of God the Son can occur in a concrete, real physical form. Because of humanity, creation is able to see the immanentization of the eschaton.

And yet, in another sense, the creation of the world is a result of a need – a need within God; this is not to say God was not free and creation was forced out of him by some greater power than God, but rather, because of the internal makeup of God being that of love, God needs to create so that God can do what God is: love:

God needs the world, and it could not have remained uncreated. But God needs the world not for Himself but for the world itself. God is love, and it is proper for love to love and to expand in love. And for divine love it is proper not only to be realized within the confines of Divinity, but also to expand beyond these confines. Otherwise, absoluteness itself becomes a limit for the Absolute, a limit of self-love or self-affirmation, and that would attest to the limitedness of the Absolute’s omnipotence – to its impotence, as it were, beyond the limits of itself.[6]

It is in love, through love, we find the incarnation, we find the self-emptying of God the Son, the Logos, so as to make sure that grace flows throughout the world, to make sure that divine love is not self-enclosed love but the ever-present, ever-flowing love of God beyond the Godhead and into creation itself. The Godman is at the heart of creation, making humanity a part of that heart.[7] He renders grace into creation the way a heart renders oxygenized blood to the body, having creation give over itself to him so that it can be purified from all that is not grace and in return be filled with that grace which is necessary for it to be transfigured and fit for eternity. This is most clearly seen in the sacraments, where, “the transcendent enters into the immanent; heaven and earth are united in such a way that they stop existing in their separateness and oppositeness.”[8]

While many aspects of our root text sometimes appear to follow the universal, perennial philosophy in such a way that it is difficult to discern whether or not the author was Christian, we get passages such as this one, which talk about the transformation of God, which demonstrate an incarnational idea and represent the fundamental Christian character of the piece. It is not, of course, proof of Anthony’s own writing of the text, but sections such as this go against the notion that the text was not written by a Christian. In its final form, as it is edited together, we clearly see here (and a few other passages) texts which imply – or directly state—Christian truths; the transformation of God because of humanity implies the incarnation of God as human. Anthony, who clearly was interested in incarnational themes (as can be seen in his condemnation of Arius), would add such touches to his text, even if he is looking to a universal, ascetic theme. As such, it helps confirm the possibility of his connection with this text.

[1] “On the Character of Men and on the Virtuous Life,” 349 (#132).

[2] “On the Character of Men and on the Virtuous Life,” 349 (#133).

[3] “On the Character of Men and on the Virtuous Life,” 349 (#133).

[4] St. Irenaeus, Proof of the Apostolic Preaching. Trans. Joseph P. Smith, S.J. (New York: Newman Press, 1952), 73.

[5] Sergius Bulgakov, “On Holy Relics” in Relics and Miracles. Trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: William B Eerdman’s Publishing Company, 2011), 8.

[6] Sergius Bulgakov, The Lamb of God. trans. Boris Jakim (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdman’s Publishing Company, 2008), 120.

[7] Hans us Von Balthasar, in words to Christ, points this out:

Everything, sin included, is to you raw material and building stones. Through your atonement you take each being to yourself and, without destroying its reality, you confer upon it a new being. You change refuse into jewels, coquetry into virginalness, and on the hopeless you bestow a future. Your sorcerer’s hand outdoes all of childhood’s fairy-tales.

Hans urs Von Balthasar, Heart of the World. Trans. Erasmo Leiva (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1979), 215.

[8] Sergius Bulgakov, “On Holy Relics,” 12.