¨Raised to the heavens, Mary remains for the human race an unconquered rampart, interceding for us before her Son and God.¨

– Theoteknos of Linas, 7th Century

Today I had the opportunity to visit Maria, Mater Misericordiae, an amazing art exhibition at the Muzeum Narodowy (National Museum) in Krakow. Planned in conjunction with World Youth Day and the Jubilee Year of Mercy, this special display showcases an eclectic assortment of medieval and early modern art collected from around Europe. The display was organized thematically, dividing the pieces into three main groups: one section focused on the Madonna nursing the Child Jesus (Galaktotrophousa) and Mary as Virgin of Tenderness (Theotokos Eleousa), a second area focused on images of Mary holding the body of Christ after the Crucifixion (Pieta), and a final section focused on Maria Orans, the assumed Mary in heaven who prays for her people and, in later medieval art, embraces us all under her mantle.

While I enjoyed the whole exhibit, I must admit that the second and third sections were the ones that resonated most strongly. Images of Madonna and Child have always somewhat problematic for me. Like many other women raised in the Catholic Church, I was taught from childhood that Mary is the feminine ideal on which I should model my own character. However, as I grew older, I found this model exceedingly hard to follow (it is, after all, exceedingly difficult for the vast majority of women to simultaneously be a virgin and mother). As the cult of Mary developed throughout the Middle Ages, theological discussions about the nature of Mary´s body abounded. Alas, it is hardly a normal female body. The medieval Mary is permitted to lactate and nurse but not to menstruate, and ultimately, the belief in the Assumption (which dates from at least the 4th century but was not dogmatically defined until 1950) exempts her from one of the most universal human physical characteristics: physical death. How am I, a physically embodied human woman, supposed to take Mary as a model for my life?

I know I am not the only Catholic woman to face this problem, but thankfully, contemporary Catholic theology of Mary has started to offer a solution. In Truly Our Sister, a book-length study of Mariology, theologian Elizabeth Johnson makes the case that the legacy of this medieval cult has led us to misunderstand the mother of Jesus. By embodying Mary with divine qualities and elevating her to the level of a mother goddess, we have succumbed to a confusion of categories. We have forgotten that God is essentially neither male or female; indeed, the Bible abounds with feminine images of God as well as masculine ones. By reminding ourselves of God´s nature – a nature that transcends gender – we can allow Mary to come down from her pedestal as an embodiment of the divine feminine. In this way, she is free to reclaim her place in the Communion of Saints.

If we look at Mary as she is portrayed in the Gospels, we see a figure who courageously risked public shame and even death when she said ¨yes¨ to the angel Gabriel´s offer to become the Mother of Jesus. She gave birth under very harsh conditions with only the poor for company, became a refugee in Africa when she learned that her son´s life was in danger, trusted in Jesus´ authority and urged him to begin his ministry at Cana; watched as he was publicly executed for crimes he had not committed, and then becoming one of the first leaders of his mission after the Resurrection.

Looking at this Mary, we see a woman who is faithful, brave, compassionate, authoritative, and thirsty for justice. In this light, her physical characteristics are not nearly as important as her spiritual ones – character traits which all of us, male and female, can seek to develop in our lives as Christians. And, it is clear that medieval artists, though eager to elevate Mary to a divine level, did not forget these divinely-given human characteristics. For me, Mary´s humanity became most evident in the Pieta images, which show Mary´s very human grief at losing her son (for what sorrow is greater than that of losing a child?)

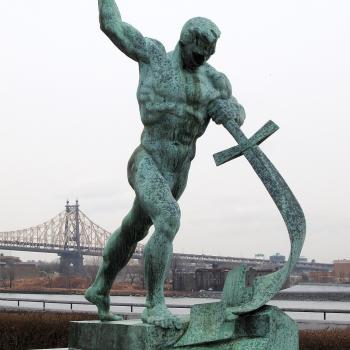

But, ironically, it also became evident in the Maria Orans images, which of course are based not on Scipture but church tradition. As I looked at such images as Barnaba de Modena´s Madonna of Mercy (1375), Francisco de Zurbarán y Salazar´s The Rosary Madonna Adored by the Carthusians (1638-1639) and Albrecht Durer´s Life of the Virgin (1511), I was again and again presented with images of Mary as a compassionate, courageous member of the Communion of Saints. Though dwelling in heaven, she is consistently concerned for her people, holding them under her mantle and binding them together through the rosary – that beautiful prayer which is perhaps the greatest gift that Marian tradition has given us.

Over the past weeks, it feels like the world has been unravelling. With intermittent access to the news, I have heard only in passing of increased race-based tension and violence in the US, racist incidents in the UK following the Brexit decision, the Bastille Day terrorist attacks in France, and the attempted coup in Turkey. Hearing one horrible news story after another, I am even more convinced of the need to respond with mercy. Not too long ago, I was asked a very challenging question: ¨Are you driven more by love or fear?¨

Unfortunately, we inhabit a political and economic arena in which fear (coupled with greed and the desire for power) are the dominating factors, and the possibility of instant electronic communications makes it even easier to become overwhelmed by fear. The Polish National Museum´s Maria Mater Misericordiae exhibit is a reminder that this fear need not have the final say. For me, one of the most beautiful passages in the gospel is Mary´s ¨Magnificat,¨ in which she affirms the steadfast love of God and the belief that a better, more just world is possible. Let us not forget that Mary also lived in a harsh, violent reality– arguably much harsher than our own. Let us not forget that she listened to the angel´s order not to be afraid. And she responded with one of the bravest affirmations in history. Today, I would like to urge all of us to be guided by love rather than fear.