Note: This post is adapted from the notes of a sermon I was invited to give on Sunday, May 12 at Christ Church, a United Church of Christ in Latrobe, Pennsylvania. As a Catholic I was thrilled by this invitation, particularly the chance to preach publicly as part of a liturgy – something my own tradition does not permit. It was an incredibly empowering experience for me, and I’d like to share with you the story I shared with the congregation this morning.

Garlic

Cancer fighter. Memory booster. Vampire defeater. Base of the fettucine alfredo, lasagna, gallo pinto. You can never have too much garlic, my mother assured me every time I put one extra clove into the sauce. But when Magdalena moves in, she tells me “no.” I like the taste, just not the smell. At first I don’t understand. Garlic-breath never bothers me; I never worry about an offensive kiss. Magdalena, maker of tamales with mushrooms, chicken soup punctured by the hottest chilies shipped by her mother in Guatemala—the reddest reds, the spiciest pimiento—waits a year before telling me the reason. When we were crossing the border, we stuffed our pockets and shoes with garlic. It was meant to keep the dogs away. My smile vanishes; jokes about vampires shrivel and fade like the bodies of the dead as my favorite food turns to pungent white pain. Today Magdalena no longer shares my home; the smell of her chili no longer waters my eyes. She has moved to another house, in hiding from the ones who would seize and jail her. Garlic again fills my soups and stews, but the delight is tinged with yearning for a world without desert walls, without dogs bred cruel, a world where imaginary lines don’t stop anyone from breathing.

It was January of 2017. For two and a half years I’d been living in Dubuque, Iowa – a beautiful town on the Mississippi River where I’d moved to take a teaching job at a small college. While there was a lot I appreciated about Dubuque – particularly the beauty of the bluffs and hills along the most iconic river in the United States – I must admit I was finding it hard to adapt to life in a small, midwestern US town after seven years living in Toronto, which is mythologized as the most diverse city in the world. I missed the vibrancy of urban living – riding the subway with people from all over the world, hearing an array of languages wherever I went, being able to attend a Jamaican drumming circle and Mexican film festival and Polish cultural event all in the same day. I was out of my element in Dubuque – particularly as an unmarried, childfree woman in a culture that seemed completely structured around nuclear families.

But Dubuque did have one strength I’d rarely seen before and have rarely seen since: a population of concerned citizens who truly aimed to live what they believed. I met a woman who has dedicated much of her life to raising awareness and resisting human trafficking. I met a father and son who had spent the previous decade managing a Catholic Worker house and directly serving people in poverty. At a time of much political uncertainty and unrest in the US, I asked myself – what can I do to make a difference in my country, right now, right here where I stand?

The answer lay in my language skills. At a time when so many people were clamoring to build walls, I also met people determined to build bridges – particularly a group of concerned citizens who got the city government to proclaim Dubuque “an open and welcoming city” for immigrants and persuaded the local police not to collaborate with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. I learned that for the previous several years, young indigenous people had been arriving to Dubuque as unaccompanied minors. Due to opportunities in agriculture (especially the meat industry) other cities and towns in Iowa have long been a destination for Mexican and Central American immigrants. But the growth of this community in Dubuque was a new phenomenon.

Because Dubuque did not have many bilingual Spanish-English speakers at the time, I soon found that my language skills could be useful to these young Guatemalans – even though, as indigenous people, they spoke Spanish as their second tongue after Ixil, Quiche and other Mayan languages. Under the guidance of an experienced interpreter, I began interpreting at legal appointments and “Know Your Rights” seminars aimed at helping immigrants – documented and undocumented – navigate systems not set up for them. At one such seminar run by Catholic Charities, I met some people who ran a nonprofit, Dubuque for Refugee Children, and soon began working with them as well.

A turning point came in the fall of 2017, when I learned that these organizations were seeking US citizens to become legal guardians for undocumented young people. The reason for this is that one of the only to citizenship for these unaccompanied minors is a program known as Special Immigrant Juvenile Status. To qualify, the young person needs to prove they’ve been abandoned by at least one parent, and they need to have a US citizen legal guardian who demonstrates that they care for them. Young people most often migrate to places where they have siblings, cousins, or other family members, but if none of those family members are citizens, they need someone to step in and become a guardian.

When I was asked to be a guardian, I initially balked. What would the commitment be? I was informed that for most people, being a guardian is really a legal formality – the young people receiving guardianship continue to live with family. But it would still be my legal responsibility to care for them.

It’s difficult for me to admit this – particularly on Mothers’ Day – but parenthood has never been something I’ve aspired to. I like the freedom of coming and going as I please, without being beholden to someone in constant need of my care. But as soon as I was introduced to 17-year-old Magdalena, something clicked. I knew I would be her guardian, and I knew it would be more than a legal formality. At the time, she – who had migrated to Iowa fleeing abject poverty in her rural hometown – was living with friends, going to school, and working nights under the table at a restaurant to pay her bills. I offered her the option to come and live with me. I would house her and provide her with food for no charge while she finished her high school degree.

And that is how, from 2018 through 2020, Magdalena came to live with me.In that moment, my life changed. As a single person in a family-centered culture, I had been deeply lonely in Dubuque, often feeling on the margins, frequently suffering from mild depression. While I did have friends, my attempts at finding an intimate romantic relationship – something I desired deeply – had failed. I hated coming home each day to a cold, dark house, cooking a simple meal to eat alone.

But now, I came home to Magdalena working on her homework, listening to evangelical Christian music. The routine of registering her in school and driving her to school helped to ground me, as did sharing food. In spring, she surprised me by planting a vegetable garden alongside our home – something I, having no green thumb, had never attempted to do. While I tried to shield her from my issues and painful emotions, there was one day when I came home in a particularly low mood. She asked me what was wrong, and I put it as succinctly as I could – “Lately I’ve been having a hard time believing in God.” A devout Christian who prayed and read the Bible daily, she started at me in perplexity. “Without God, you wouldn’t even be here.”

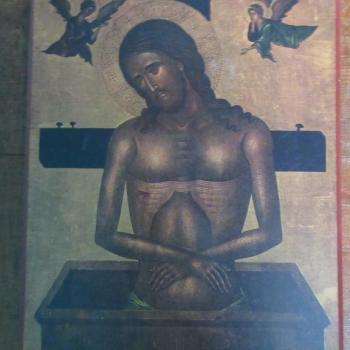

That message stuck with me. I took great pride when, on my request, Magdalena visited the college where I was teaching. In a theology class called “Jesus is not white,” Magdalena spoke about her own faith journey and belief in Christ’s redemption. My students – so often buried in their phones – looked up at her with interest and curiosity. After her talk, they plied her with questions. What do you most like about the US? they asked. What do you miss from home? What she misses from home, besides her mother, is the good quality food. What she likes most about the US is the opportunity to work, but to be able to take breaks – to visit a park, to celebrate a birthday – rather than working constantly just to survive.

Magdalena lived with me for two years until, in 2020, we parted amicably over differences in how to handle the COVID-19 pandemic. While she graduated from high school, she did not get legal status in the US due to a discrepancy over the meaning of the word “juvenile.” Though the national legal definition is someone under twenty-one, in Iowa it is someone under eighteen – and since she applied for Special Immigrant Juvenile Status when she was over eighteen, the US government decided not to grant her status. Today, she is one of millions of people living and working in the shadows, with no path to legal status possible under our current system. Mothers’ Day is a painful day for her, as she cannot go back and visit her own mother.

Meanwhile, it is also a beautiful day, as she herself is the mother. Two years ago, she and her long-term partner Cruz – whom I, like any protective stand-in parent, scrutinized and sized up – had a beautiful daughter, Ana Edilza. Like so many of our ancestors who migrated to this country, like so many immigrants today, Magdalena is doing everything she can to raise her daughter with the opportunities she herself did not have.

I share this story with you for many reasons. As politically divided as our nation is, I believe people on all sides can agree that our immigration system is broken. But as we sift through the sound bites and rhetoric, let us not forget that the people who hang in the balance are just that – people, with the same basic dignity and desires that all of us have: to work, to make something of our lives, to form meaningful relationships, to enjoy life in the company of family and friends. Because of the experiences I’ve had – not only serving as guardian for Magdalena, but for two other young people who did not live with me, and then interpreting at five childbirths – any dehumanizing rhetoric toward immigrants brings out all my maternal instincts with a vengeance. Though I’ve never given birth, I am unapologetically a “mama bear,” with all the passionate protectiveness that term entails.

And that brings me to my next point. In this culture – indeed, in most cultures – it can seem like sacrilege for a woman to openly state that she doesn’t want children. Women without children are looked askance as suspect, as selfish, as somehow deficient. But I maintain that there are many, many ways for all of us – regardless of gender – to contribute to the flourishing of our world, to nurture and raise the next generation, to offer generous love and care to those who most need it. Let us remember that “mother” is a verb as well as a noun. To show warmth, kindness, and gentle care – traits increasingly devalued in our hypercompetitive society – is the calling of all who purport to follow Jesus. Some of Jesus’ closest friends were women: Mary and Martha as well as my former ward Magdalena’s namesake, Mary Magdalene, who was not a prostitute or sinner as Pope Gregory made her out to be, but a friend, companion and the first witness to the Resurrection. There is no Scriptural evidence that any of these women had children – we remember them as loyal, faithful discipleship of Jesus, which is what we are all called to be. It is this discipleship that Magdalena modeled for me and still does. I will close with one more poem.

Magdalena

Having risen in the morning on the first day of the week, [Jesus] appeared first to Mary of Magdala […] She then went to those who had been his companions, and who were in mourning and in tears, and told them. But they did not believe her when they heard her say that he was alive and that she had seen him. —Mark 16:9–11

First witness to the Resurrection,

you were the one who set out in darkness,

came to the spot, saw the stone rolled away,

went running to tell the apostles

who didn’t believe you

not only because you were a woman,

but because you didn’t have a passport

or even a green card

because you worked in a back kitchen

under a false name

because your English had a heavy accent

because you still preferred tortillas over bread

and said our hamburgers were the worst food you’d tasted

because you didn’t know how to drive,

still wishing for a store and school close enough to walk to

because you’d crossed behind a “No Trespassing” sign.

Previously, I’d been a faithless apostle.

Like them I fled from the foot of the cross

flitted between distracting lovers and lies

hid for long hours at work

returned each night to a cold, dark box

heat and light turned off poured myself a beer

to drink alone

But today when I come home

the stove sings with boiling carrots,

your potato soup

steaming corn tortillas

I sip your arroz con leche

while you savor my chocolate chip cookies

you don’t ask if I believe in the Resurrection

you just request help studying for your history test

and the marvelous story you offer

is that of your own desert crossing

the garlic you stuffed in your pockets

to keep the dogs away

the river’s piercing water

the squad car waiting on the other side

your resurrection tale, like hers,

is a question a dare, a rebuke, a demand:

Magdalena, apostle to the apostles

today I give you my answer:

I believe