Go to these links for Part I and Part II.

A Caution

These three posts deal with Judaism and its relation to Christianity quite a bit. I’ve done my best to research, and learnt some interesting things in doing so, but I am not an expert. I don’t even have a basic degree in this, like I do in Classics. I’m an amateur with Google and a copy of the Mishnah1; in other words, I’m an amateur. I’ve done my best to be aware of differing Judaic traditions, and not to overstate my certainty about the meaning of this or that. But I’m not perfect, and, to my chagrin, that may be provable from what I’ve written here! If anyone who does have a degree in Jewish studies—better still, a rabbi2—finds mistakes in this, please let me know. I don’t want to spread misinformation at all, and especially not about Judaism, which, to put it delicately, Catholics have really spread quite enough misinformation about for at least seventeen centuries now. (And this, of a people and faith we ought to treat with a peculiar respect and sensitivity; but I digress.)

The Verse (RSV and my translation)

A confessional in Jaromer, Czechia.

And when he had said this, he breathed on them, and said to them, “Receive the Holy Spirit. If you forgive the sins of any, they are forgiven; if you retain the sins of any, they are retained.”

And having said this, he blew on them and told them: “Receive the Holy Spirit; if you remit anyone’s sins, they are remitted to them; if you hold onto anyone’s sins, they are held onto.”

—John 20.22-23

This is a verse that caught my attention in high school, because it didn’t seem to have any clear explanation in the context of the Reformed theology I grew up with. I was, by that time, loosening my grip on the “Catholic interpretation of a verse, ipso facto wrong” approach to things; but I wasn’t yet ready to accept this as a proof text of the sacrament of penance, especially as it contained no mention of doing penance to be forgiven of your sins. (Which, of course it doesn’t, that isn’t what penance is for or how it works—but we’ll get to that.)

Incidentally, looking back at my upbringing, I’m slightly stunned at the placid confidence with which several of my teachers asserted that “the Old Covenant had no grace in it.” … Yes it did? What are you talking about, of course it did? You don’t even need to read the Mishnah to find this, it’s right there in the Bible, right in the part we share with the Jews! This ability, or mission, that Jesus is giving the apostles is a new application of a concept that already existed in Judaism, not a completely novel invention.

Let’s put this verse back into its original context—which is not exactly a Catholic context. Certainly it is not the Catholic practice surrounding this sacrament as we know it today; the Church has evolved quite a bit in two thousand years.3 The context this arose in, like everything else about primitive Christianity, was the context of Judaism.

The Doctrine of Pardon

“Without shedding of blood,” the author of Hebrews states categorically while discussing the Torah, “there is no remission.” Sacrifice was a normal and normative element of Judaic worship, right up until the destruction of the Second Temple. Some offerings were obligatory, and all holidays were associated with a special sacrificial liturgy of some kind, but Israelites could bring offerings to the Temple throughout the year, both on holidays and by personal choice. These were often for reasons of ritual purification or as acts of thanks; not all were blood sacrifices, nor were all of the dozen-odd types of offering about atoning for some offense,4 but repentance was a standard reason to bring sacrifices to God.

The greatest ritual of divine pardon was Yom Kippur, which—besides the usual daily sacrifices—involved making offerings for the whole priesthood and the whole people of Israel; this was the only day on which the Most Holy Name was uttered, and the only day on which the Holy of Holies was entered, both functions only the high priest could fulfill. The liturgy of this day was held to obtain pardon for the whole people of Israel.

Same thing I’m sure

However, it’s important to recognize that templar sacrifices were not understood by the Jews as magic. This was not a more-involved version of waving a wand and declaring the guilt had gone bye-bye. Repentance was a necessity for forgiveness; in the case of serious sins against one’s neighbor, apology and restitution were also necessary, a lesson they got not from “works-righteousness” but from the prophets.

The Sin-offering and the unconditional Guilt-offering effect atonement; death and the Day of Atonement effect atonement if there is repentance. Repentance effects atonement for lesser transgressions against both positive and negative commands in the Law; while for graver transgressions it suspends punishment until the Day of Atonement comes and effects atonement.

If a man said, “I will sin and repent, and sin again and repent,” he will be given no chance to repent. “I will sin and the Day of Atonement will effect atonement”—then the Day of Atonement effects no atonement. For transgressions that are between man and God the Day of Atonement effects atonement, but for transgressions that are between a man and his fellow the Day of Atonement effects atonement only if he has appeased his fellow.

—The Mishnah, Div. “Festivals,” tractate “The Day”

In Judaism, reasoning from the principle that the wronged party in a sin is the person in a position to extend or refuse forgiveness, sins against God can only be forgiven by God, and sins against one’s neighbor can only be forgiven by that neighbor. This reasonableness is more frightening than it may sound on the surface, because the Torah does not strictly contain a command to forgive; one could certainly argue that this duty was implied,5 but it was not laid down unambiguously. Besides this, the mere fact that people have a duty does not mean they’re going to observe it. If that were how the Torah worked, it would hardly need to contain rules about how to conduct murder trials.

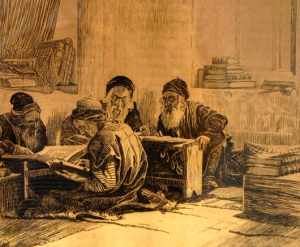

Talmud Students, Ephraim Moses Lilien,

late 19th or early 20th cent.

So the question does arise: What if the person I’ve wronged will not or cannot forgive me? To which, so far as I can tell, the answer (or at least the most common answer) in Judaism is, “Then you aren’t forgiven.” For example, murder—except in the exceedingly unusual circumstance of the victim forgiving the perpetrator before actually expiring—cannot be forgiven. Relatives of the victim can forgive the murderer for the anguish he has caused them, but not for the murder itself, because they’re not the one who got murdered.

This might strike Christians as shockingly unreasonable; but when you have a think, you may realize that really, it’s the Christian doctrine of pardon that is unreasonable, shockingly so.6 That is part of the point. It’s doubtless why so much time in the Gospels is devoted to both the importance of pardon in theory, and to actual pardon dispensed in practice, from the height of Jesus’ popularity to the moment he asks his Father to take pity on his executioners. It also lends some interesting color to the Resurrection, which must be presumed to change the dimensions of possible forgiveness, but we’ll come back to that.

“Thy Sins Be Forgiven Thee”

The doctrine that the only person who can pardon a sin is the victim of the sin may appear to conflict with the implied view of the Pharisees recorded from the episode with the paralytic: “Who can forgive sins but God alone?” However, I’m not sure this really is a conflict. Keep in mind that Judaism is defined by a law rather than a creed;7 this means that even fairly basic differences in belief have more leeway in Judaism than they ever could in Christianity.8 I’m not clear at what point in Judaic history the case of a victim who could not or would not forgive received the answer that is now held to be consensus. It’s possible, as far as I know, that this doctrine developed later in the Tannaitic9 period than the life of Jesus; in that case, “Who can forgive sins but God alone?” might represent an earlier view, held by at least some Pharisees. Alternatively, something about Jesus’ statement might have implied that he was speaking specifically about sins against God (his specific choice of Aramaic or Hebrew word, for instance).

Title page of the Midrash Tehillim,

a commentary on the first 118 psalms.

Additionally, there seem to be wrinkles in the idea of pardon between men: for instance, following up on the murder example above, I’m given to understand that the standard view in Judaism is that murderers who have not been forgiven by their victims (so, presumably, nearly all murderers) will be answerable to God at the Last Judgment. That obviously implies that God has some type of involvement here. I imagine the explanation is in the many volumes of the Talmud, or somewhere like that; I’m not sure where to find it.

But let’s return to the New Testament. In the story of the paralytic, it sounds as if one of two things, both outrageous, were true. The first option was mentioned above: something about the context or the wording implied that the sins Jesus was claiming to absolve were specifically sins against God. This would dovetail more neatly with the theology we find in the Mishnah, on the condition that we accept the claim that Jesus was God. (Disputes about harmony with the Mishnah may seem like they pale in comparison with that question, but that’s really neither here nor there: if we say he was not God, then the importance of the Mishnah is surely not affected by one weirdo rabbi; if he was God, the context the Mishnah gives to his theology probably matters more.)

The second option is that he was indeed claiming to absolve the man’s sins in general, which is how Christians usually interpret the text. This view seems to me to be the more reasonable one. I don’t honestly know how this could dovetail with Judaic theology; but I find it hard to see how any sin against our neighbor is not also, by nature, a sin against God—both because he is the one who gave the Torah in the first place, including all the commandments it contains about love of neighbor, and because man is made in the image of God (and God is thus, at minimum, symbolically or ritually sinned against whenever we sin against our neighbor). For that reason, while we still have a duty to apologize and make appropriate restitution to those whom we have wronged,10 the forgiveness of any and every sin, whether against our neighbor or not, does redound to God.

This interpretation also seems to align with Jesus’ own behavior. The episode with the paralytic is far from the only example of him claiming to pardon sins. Quite independently the sacrificial system, he informed people of divine pardon repeatedly—he often does it seemingly apropos of nothing!

The Return of the Prodigal Son by James

Tissot, 1850. I was surprised how much this

moved me; it never occurred to me to imagine

them reuniting in front of other people.

And it wasn’t like he was declaring the templar system invalid, either, the way an Essene would, in which case some other means of forgiveness would seem so urgently necessary that approving an arbitrary novelty would become psychologically acceptable. On the contrary, he goes out of his way to send those he has healed to the Temple for verification; he goes there himself, both on pilgrimage feasts and for lesser festivals; even when speaking with the Samaritan woman at the well, a conversation in which he hints that the Temple is not in itself the point, he essentially says, “But since you bring it up, yes, in the Jerusalem-Gerizim dispute, it is the Jews rather than the Samaritans who have the correct answer.” He is claiming a capacity to extend divine pardon at will, while at the same time adhering to the full ritual panoply of the Temple. As far as I know, there is only one figure in the doctrine of any Abrahamic religion who would or could do that.

The Air Apparent

“Okay, but what does all this have to do with John 20.22-23 and this distinct giving of the Holy Ghost?”, you may be asking.

Well, here Jesus has been on earth, going around forgiving people upstairs and downstairs and in my lady’s chamber. He claims that he received the charge to do this from his Father. Then, after the Resurrection—which, remember, dramatically alters how forgiveness can theoretically operate—he tells the apostles that he is sending them, in the same way his Father sent him; then, he tells them that he is giving them the Holy Ghost, and that they have the authority to forgive or retain sins. This text does not mention him laying hands on them, which was a standard symbol of semikhah, rabbinic ordination, and apparently one picked up afterward by the apostles themselves, but the laying on of hands was not considered essential by most authorities. What was essential was, first, that a rabbi was not merely training people who agreed with him, but apprentices, just like the apprentices of a craftsman; and second, that a candidate for semikhah be recognized as qualified, by someone qualified. (The link between this and the doctrine of Holy Orders is probably obvious.)

To all appearances, then, the apostles are being given the task of pardoning sins, exactly as Jesus has spent the last three years pardoning them. They had already been appointed to his lesser ministries of preaching the Gospel, baptizing people, healing sicknesses, casting out devils, and being penniless. They had even been told (beginning with Peter, but later extending to the other eleven) that they had the power to “bind and loose,” standard terminology for making halakhic rulings. Now, they were being appointed to the truly awe-striking destinies: absolving sins, and, as a later episode assured Peter, martyrdom.

And if the apostles do have the power to forgive, the rest of the apparatus of confession—the requirement to actively come to them and confess, the appropriate secrecy surrounding that, the new duty of penance that replaces the old duty of sacrifice—all this honestly does seem to me like a logical and natural outworking of the theological core these verses express.

Is This Really the Sacrament of Confession, Though?

Yes.

Okay, I’m not actually going to leave the explanation there. There’s a reason the Church claims this little verse as the basis of a whole sacrament. You see, there’s something we’ve left out of the discussion of pardon thus far, a question that we haven’t yet asked.

Mary, Untier of Knots, painted in 1700 by

Johann Georg Melchior Schmidtner, a name

than which none Germaner can be conceived

Let’s go back to that extreme case, the case of murder. The Pharisees, and accordingly Christians once we came into being, believed in a soul that continues to exist after the death of the body. Early in Christian history, there were debates about what’s called “the intermediate state,” between death and the Last Judgment (before which the general resurrection of all the dead is supposed to take place); some people held that the soul “sleeps” in this intervening time, but the consensus belief was increasingly one of conscious, continuous life, and this seems to have been true in Judaism too, or at least in some strands of it. So if that’s true, then why couldn’t the dead victim of a murderer absolve the person who killed them?

I can think of two answers. Both seem, to me, to line up with Catholic practice. One is that forgiveness needs to be received as well as willed, in order to actually take effect; the other, that forgiveness can be effected without informing the forgiven person that they’ve been forgiven, but how are we to know about it? and a fat lot of good it’ll do the sinner if they don’t. It isn’t as if we can simply decide that we know God’s mind about something like this, is it? That would corrupt the nature of forgiveness, which is supposed to reconcile two people. (It’s this, incidentally, which inclines me to think the first idea, the one about receiving pardon being part of pardon, is the more fully correct one.)

Either way, the importance both of Jesus’ ministry of forgiveness and the apostles’ inheriting that ministry is that it is good news—news being something that’s made known to people. This is part of the reason we connect this to apostolic succession; this need for forgiveness did not change or go away after the Twelve had all died. Jesus commissioned the apostles to pardon people when he was gone because pardon is not generic, it is personal, and because pardon is not an applied theory, it is a specific decision. And the Twelve, who were Jesus’ apprentices before and fully-fledged rabbis now, passed that gift they had received on in turn.

A Conclusion, in Which I Break the Rule I Didn’t Make for Myself

The seal of the Holy See

I used to write a lot of apologetics, right after my conversion. Eventually I got very tired of how unproductive that was. It turns out both that attempting to win conversations is weirdo behavior, and also that the sort of people who reply to the invitation “debate me you cowards” are—how can I put this delicately—assholes. And both of these facts have effects not only on apologetics, but on apologists. I never formally swore off apologetics, but I became, and remain, highly pessimistic that it does most people much good, and least of all apologists themselves.

Moreover, I don’t like to dunk on Protestants, for three major reasons. First of all, my mother is one, thank you very much; second, I owe them thanks and honor, because they’re the ones who taught me to love Jesus and the Scriptures. Even at my post-convert worst, while I definitely got smug sometimes, I never lost my sense of gratitude or respect. And third, in my opinion, there is far, far, far too much arrogance about Protestants in Catholic circles in the first place, and it is very ugly and shameful.

“Carpet page” from the Lindisfarne Gospels

However—with that caveat firmly in mind—I’ll admit to finding a stock Protestant saying about this rather funny: namely, the one about “going straight to God for forgiveness” (itself rooted in the idea that the priesthood is interposed between God and believers in general by Catholics, as some kind of middle man). Are you saying that when you pray for forgiveness, Jesus appears to you personally and declares that he forgives you? I mean, if that is what you’re saying, wow, that’s extremely impressive! But I haven’t yet found that this really is what Protestants are usually claiming.

It would seem, instead, to be an assertion that asking for forgiveness and having it are, to them, one and the same. That sounds to me like it’s far more open to what is, for some reason, instead a stock accusation against Catholics, i.e. that we can “just” go to confession and everything’s alright. Or are you forgiving yourself with God’s authority?—because I don’t know how you propose to claim that authority. This gift of the Spirit clearly isn’t the same as the outpouring at Pentecost: there, the whole Church received it in such a dramatic fashion it sent them tumbling into the street, and there was no suggestion of them all having a ministry of absolution, nor is there in the later pages of Acts; here, only the apostles are present, the Spirit is given in an almost secretive setting, and Jesus explains their new function to them because what he has done is so un-obvious.

In short, the Catholic explanation of the priesthood’s role in forgiveness is … exactly what the Church says it is. Jesus acts through the priest, just as he might act through any of “the least of these, my brethren,” but with the advantage of being a designated representative, not just something we’re telling ourselves; the priest makes him more present, not less, so that we can interact with a person and not just a principle.

This picture of Shamgar son of Anath isn’t

here for a real reason; I just like him—he

slew of the Philistines six hundred with an ox

goad, you know (and also delivered Israel).

Footnotes

1The Mishnah (“the review”) is a compendium of rabbinic teaching dating to roughly the first two centuries CE, probably compiled in or around the year 189; the Talmud is largely a commentary on it. It is arranged in six sedarim (“orders” or “divisions”), which are in turn subdivided into tractates, with around ten tractates per division. The Mishnah can’t be identical to the kind of Judaism observed by and in the time of Jesus—several kinds of Judaism were practiced during his lifetime, and it records multiple rulings on questions of moral and ritual practice. However, the Mishnah almost certainly preserves most of the important details on late Second Temple period Judaic practice, and specifically what Jesus would have followed as an observant Pharisee. (If “Jesus was a Pharisee” sounds insane to you, I’ve explained that at greater length in this post, chiefly in the section “The Least Stroke of a Tongue” and the second footnote.)

2Not that I think it’s likely a rabbi would spend his free time reading a random gay Catholic dork’s commentary on the New Testament. But on the off-chance!

3One of the better-known developments of Catholic doctrine and practice alike, which has influenced not only our theology but even our architecture, is that of the seal of Confession. You are, after all, confessing your sins to God, who acts in the priest’s acts—the priest is there for your benefit (not God’s, and certainly not his own!), but your private sins are still not his business. It is therefore theologically appropriate that priests should seek to know and retain as little as possible about penitents. However, the seal of Confession is thought to have originated in the Irish Church, from which it presumably diffused during the Irish missions of the sixth to eighth centuries. Before that time (at least in some places), far from being kept secret, confessing meant joining the order of penitents, who wore distinctive clothing and were temporarily banished from the eucharistic liturgy.

4Indeed, I gather only two types of sacrifice were explicitly concerned with sin: the קָרְבַּן חַטָּאת [qorban chaṭṭa’th], usually translated “sin offering,” though the word used here for sin implies what Catholics would probably call a venial sin; and the קָרְבַּן אָשָׁם [qorban ‘asham], meaning “guilt offering” or “trespass offering.” Both sacrifices were for restricted sets of offenses.

5The commandments numbered 11, 13, 14, 15, 20, and 21 in the list of Maimonides arguably imply a duty to forgive. If we are to walk in the ways of the Lord our God (11), love our neighbor as ourself (13), love the stranger (14), not hate our brother in our heart (15), not avenge (20), and not bear any grudge against the children of our people (21), there’s not a lot of elbow room left for refusal to forgive. Additionally, rabbis have long emphasized the duty to be easily appeased, patient, indulgent, and merciful.

6Lest I be misunderstood: it does not follow that the Christian doctrine of pardon is untrue. “Reasonable” and “true” are quite different things. This is key to the idea of presumption in moral theology; presuming upon God’s grace is treating grace as something you have a right to, instead of as a gift.

7More properly, of course, Christianity is based on a person, Jesus—but because that person was a rabbi, part of accepting him is accepting his particular midrash, his specific teaching about the Torah. This can be conveniently summarized in a creed in a way that Judaism, which does not require subscribing to any specific rabbi’s midrash, cannot.

8This isn’t to say there can be no strictly philosophical debates in Judaism or that Judaism involves no belief. Conservative Jews have espoused a basic statement of faith since 1988; Orthodox Jews often refer to the thirteen principles of faith, defined by Maimonides in the twelfth century, as a summary. However, these statements of faith, not being part of the Torah, are (quite naturally) not treated as binding the way the Torah is binding. Debates in Judaism tend to be halakhic—i.e., concerned with the interpretation and application of the Law—rather than doctrinal.

9The Tannaitic period ran from 10 to 220 CE, and was defined by the Tannaim, or “repeaters,” the main class of scholars who contributed to the Mishnah. It is thus related to and overlaps with, but not the same thing as, the Second Temple period (ca. 516 BC-70 CE): the first sixty years of the Tannaitic period, while the Temple was still standing, featured other kinds of Judaic theology than that of the Pharisees, notably Sadducee and Essene theology. The Tannaim succeeded the Zugoth, “pairs,” five sets of leading scholars of the Torah. The Zugoth wielded influence from the Maccabean Revolt, 167-160 BC, until the death of Hillel the Elder in 10 CE. The best-known are the last pair, namely that same Hillel and Shammai. (It is completely unprovable, but I’m tickled by the idea that when Jesus was stranded in the Temple for a few days, right around bar mitzvah age, he may actually have conversed with Hillel and Shammai.)

10Indeed, this duty applies even to sins that have already been forgiven. The injured party can waive this duty as an act of generosity—that’s what an indulgence is, and why absolution is needed first to obtain one—but it is, precisely, waiving a duty we would otherwise have. The fact that Catholic teaching about the sacrament of penance tends to ignore or downplay this duty is, in my opinion, not great.