A Law in Review

To put the Gospel from Shrove Sunday (11 Feb. this year) in context, I’m opening with a discussion of Biblical leprosy. If, for one reason or another, you prefer to pass over that juicy pustule, skip down to the passage here.

A portion of the Temple Scroll,

the longest of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

This passage (which was the Gospel for the last Sunday before Lent this year; you may have gathered I’m a bit behind!) deals with a man with leprosy, so it will be worth our while to take a moment to review the portion of the Torah dealing with lepers. Or, well, with “leprous diseases,” given—well, look:

This is the law for all manner of plague of leprosy, and scall, and for the leprosy of a garment, and of a house, and for a rising, and for a scab, and for a bright spot: to teach when it is unclean, and when it is clean: this is the law of leprosy. —Leviticus 14.54-57

The Hebrew term traditionally rendered “leprosy” is tzaraath or tsaraȝath [צָרַעַת], and seems to have denoted multiple diseases. Not only is it something that can infect articles of clothing and houses, as well people (which would seem to suggest some type of fungal infection), but there are several different, rather confusing, symptom profiles that all qualify as tsaraȝath in a person’s skin. Leviticus 13 lists at least half a dozen distinct varieties:

When a man shall have in the skin of his flesh a rising, a scab, or bright spot, and it be in the skin of his flesh like the plague of leprosy … and when the hair in the plague is turned white, and the plague in sight be deeper than the skin of his flesh, it is a plague of leprosy …

And if a leprosy break out abroad in the skin, and the leprosy cover all the skin of him that hath the plague from his head even to his foot, wheresoever the priest looketh; … he shall pronounce him clean that hath the plague: it is all turned white: he is clean. But when raw flesh appeareth in him, he shall be unclean. …

The flesh also, in which, even in the skin thereof, was a boil, and is healed, and in the place of the boil there be a white rising, or a bright spot, white, and somewhat reddish … and if, when the priest seeth it, behold, it be in sight lower than the skin, and the hair thereof be turned white; the priest shall pronounce him unclean: it is a plague of leprosy …

Or if there be any flesh, in the skin whereof there is a hot burning, and the quick flesh that burneth have a white bright spot, somewhat reddish, or white … if the hair in the bright spot be turned white, and it be in sight deeper than the skin; it is a leprosy …

If a man or woman have a plague upon the head or the beard … if it be in sight deeper than the skin; and there be in it a yellow thin hair; then the priest shall pronounce him unclean: it is a dry scall, even a leprosy …

And if there be in the bald head, or bald forehead, a white reddish sore; it is a leprosy …

Fourteenth-century illumination of two lepers

being refused entry to a town.

If you’re thinking “Maybe it would be less confusing if you didn’t insist on using the King James,” I mean, … no? Modern scholars have identified more than twenty possible candidates for whatever tsaraȝath may have been—that is, assuming that it was a disease proper at all, of which more in a moment—including such candidates as (caution: pictures) erysipelas, vitiligo, ringworm, and the heartbreak of psoriasis. Curiously enough, few to none of the symptoms correspond to Hansen’s disease, which is what “leprosy” normally means today. That interpretation of tsaraȝath came about with the translation of the Hebrew Bible into Greek.

How Do You Solve a Problem Like a Leper?

More practical are the Torah’s instructions for what to do with sufferers from tsaraȝath:

The priest shall pronounce him utterly unclean; his plague is in his head. And the leper in whom the plague is, his clothes shall be rent, and his head bare, and he shall put a covering upon his upper lip, and shall cry, “Unclean, unclean.” All the days wherein the plague shall be in him he shall be defiled; he is unclean: he shall dwell alone; without the camp shall his habitation be. —Leviticus 13.44-46

Seems kind of harsh for people who are already the victims of a nasty illness! However, a couple of points bear consideration. One is that provisions were also made for lepers being pronounced clean: whatever tsaraȝath was, it did not necessarily mean being permanently banished to the fringes of society. Moreover, if tsaraȝath was contagious (or, supposing it meant multiple diseases, if any specific form of it was), then isolation might have been a necessity, to protect community health.

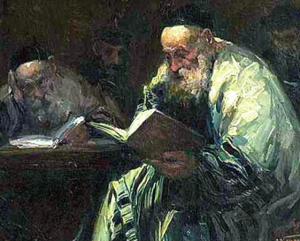

Talmud Readers [Talmudysci], by Adolf Behrman;

date unclear, but before 1943, when Behrman

was killed in the Holocaust.

The second point modifies the picture a good deal more radically, maybe. We’ll come back to that “maybe.”

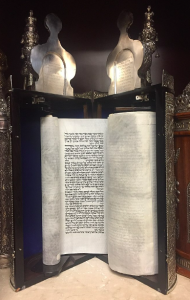

To contextualize the provisions of Leviticus, which is part of the Written Law or Torah Shebbikthav [תּוֹרָה שֶׁבִּכְתָב], we must once again turn to the documents that relate the Oral Law or Torah Shebb’ȝal-Peh [תּוֹרָה שֶׁבְּעַל־פֶּה]: i.e., the Mishnah and associated literature of the Tannaitic period; we glanced briefly at this topic in the post for Septuagesima Sunday’s Gospel. A quick-and-dirty summary goes as follows.

The Least Stroke of a Tongue

When Moses met God on Sinai, along with the actual set of specifiable statutes in the Torah—the famous six hundred and thirteen mitzvoth—he was also given principles for understanding, interpreting, and applying the commandments. These were committed to memory rather than written down, and form the basis and much of the substance of Judaic theology and jurisprudence, known collectively as halakha [הֲלָכָה] (a little like fiqh in Islam). Why would the Torah be transmitted in two differing methods like this? I am absolutely sure that question has been raised in Judaism, but unluckily it isn’t one I happen to know any accepted Judaic answer for. I have a couple of guesses: given the love of questions and argumentation that has marked Jewish culture literally for millennia, I assume that at least one answer is probably roughly So that human beings (and specifically the Jews) would thus be spurred to do the work of preserving them and keeping them together, a possible antidote to apathy and formalism.

A more postmodern-y explanation occurred to me too. This distinction between the written and oral aspects of a document may not be as odd as it sounds in the first place. All books are written in some language or other, and languages change with time—in pronunciation, in vocabulary, in structure, and also in the material circumstances they are describing.Without some kind of, well, tradition to preserve the context it was originally composed in, important nuances would rapidly be lost; before long, whole words or senses drop out, perhaps surviving only as “religious” terms, which can be disastrous or hilarious at the wrong moment. (In other words: I’m sorry, Myles Coverdale, on the whole I love your translation of the Psalter, but I will simply never be able to pray your rendering of Psalm 86.14 with a straight face—”congregations of naughty men have surrounded me” is just not gonna work, bro!)

To take a somewhat parallel example, many current debates in American law and politics revolve around the distinction between a textualist interpretation of the constitution and an originalist one. Both would concede that we must look to historical context for the then-current meanings of words; but an originalist would tend to argue, beyond that, that we should also do our best to divine the founding fathers’ intent, e.g. by taking their other writings into account and seeing what principles they sought to uphold. Meanwhile a textualist would argue that, in a sense, the intent of the founders doesn’t matter: what matters is what they actually did enshrine in law, and that is determined by the words they wrote here, not in general. You can see the same ideas and distinctions at work in this exchange from A Man for All Seasons (the film version—I can’t remember whether it’s in the play):

MEG: They’re going to administer an oath! About the marriage!

THOMAS: But what is the wording?

MEG: What does it matter—we know what it’ll mean!

THOMAS: An oath is made of words. It’ll mean what the words say.

Part of the idea of the Oral Torah, then, would be (speaking very roughly) to keep clever-dicks of the St. Thomas More type from tiptoeing their way through the law instead of bowing to it.

In any case it is the Shebbikthav and the Shebb’ȝal-Peh taken together that constitute the Torah as a coherent body of law, at least according to the Pharisees. Historically, the Essenes and Sadducees did dispute this, as did (and do) the Karaite and Samaritan branches of Judaism. But remember, Jesus himself was a Pharisee.** Judging from his willingness to modify or even contradict long-established customs, and to promulgate his interpretations in his own name no less, it seems unlikely that Jesus accepted everything that advertised itself as part of the Oral Torah. However, he certainly would have been raised to be quite familiar with the idea and its general content; and he seems to have been sufficiently comfortable with the concept that he tells his disciples that “The scribes and Pharisees sit in Moses’ seat: therefore do and observe whatever they tell you to” (Matthew 23.2-3).

… So?

This is relevant to the issue of leprosy because the most common interpretation of tsaraȝath among rabbis, past and present, has been that it is a disease with a strictly spiritual cause. (Note, for instance, that Leviticus instructs the sufferer to seek out a priest rather than a doctor. Medicine has long been associated with priests in many cultures, of course; however the Levitical priesthood did not habitually function as physicians, nor does the Torah seem to expect them to.) Tsaraȝath was thought to be caused only by some of the gravest sins,† and to be curable only through repentance. The fact that it had different forms affecting skin, houses, and clothing was interpreted by the Midrash Rabbah‡ as indicating successive stages of the disease: first afflicting a house,‡ then clothing, then laying hold of the person’s own body. Only if this fourth stage was reached and the person remained impenitent would the tsaraȝath persist, and only at this point was isolation from the community resorted to.

On top of all this—and this fits into a broader pattern of how the Written Torah has generally been interpreted by Jews—the Oral Torah placed yet further restrictions on the disease and obstacles to its diagnosis, by means of all sorts of exceptions and even, there’s no other word, loopholes. It could not affect Gentiles; it was not technically against the Law to let a priest with bad eyesight perform the inspections; it was even argued that, if the identifying symptom was whitened hairs, simply plucking out any whitened hairs suffices to avoid a diagnosis of tsaraȝath!

Returning to That “Maybe,” Though …

The complicating factor is: when did these policies about the disease take effect?

A replica of the Gezer calendar, a 10th-century BC limestone tablet,

discovered about 20 miles west of Jerusalem. Note the script:

this is the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet, used before the introduction

of the Aramaic “square” letters now associated with Hebrew.

Used under a GNU free “copyleft” license.

You see, we don’t possess the Oral Torah as it may have existed before it was codified in the Mishnah; and that was first done by Judah ha-Nasi in the year 189, about a century and a half after the time of Jesus. That probably isn’t long enough for Judah ha-Nasi’s work to have become unrecognizable to somebody like, say, Hillel the Elder, who was elderly but very much alive when Jesus was born; but it’s plenty of time for a lot of development on a few specific topics or principles. And while the treatment of lepers we see in the Gospels does not appear to line up with the leniency called for by rabbinic precedent—unless all of these people were hardened impenitents—it does appear to line up with a somewhat literal-minded reading of Leviticus, or at least a reading not informed by resources like the Mishnah. So I can’t help wondering whether, despite his excommunication, Jesus had an impact on the development of Tannaitic Judaism all the same. I am an amateur and may be quite wrong, but the Orthodox Jewish teaching that breaking the normal laws of the sabbath to save a life is not just permitted, but obligatory—to me, that sounds more like the teaching of Jesus than the teaching of the Pharisees he was disputing in passages like Mark 2-3 or John 5.

(All this is without raising the question of how comfortably the rabbinic view of tsaraȝath can really sit alongside, say, the Book of Job; but I have a hunch that if I try and evaluate that, I will be decidedly exercising myself in great matters, and in things too high for me, so for once in my life, I’m gonna leave that one be!)

We seem, then, to face a dilemma: in first-century Palestine, either (a) there were a substantial number of people who had made it all the way through to the most extreme form of tsaraȝath without repenting at any stage, or (b) the discussion about how to interpret the Levitical law about tsaraȝath had not yet been settled in the early Tannaitic period, and a more literal application may have prevailed at least for a time. Both views seem plausible to me; I have not been able to find sources that could resolve this question. That isn’t to say they aren’t out there, but, well, this is a one-man blog (written by a Goy) and I have a job, so in any case I haven’t found them. (Information from those who may happen to have it is welcome!)

Mark 1.40-45, RSV-CE

And a lepera came to him beseeching him, and kneeling said to him, “If you will, you can make me clean.” Moved with pity,b he stretched out his hand and touched him, and said to him, “I will; be clean.” And immediately the leprosy left him, and he was made clean. And he sternly charged him, and sent him away at once,c and said to him, “See that you say nothing to any one; but go, show yourself to the priest, and offer for your cleansing what Moses commanded, for a proof to the people.”d But he went out and began to talk freely about it, and to spread the news,e so that Jesus could no longer openly enter a town, but was out in the countryf; and people came to him from every quarter.

Mark 1.40-45, my translation

And a lepera came to him, appealing to him and kneeling, saying to him that “If you will, you can cleanse me.” Impassioned,b he stretched out his hand and laid hold on him and said to him, “I will; be cleansed”—and right away the leprosy left him, and he was cleansed. And, sternly warning him, he put him out right away,c and said to him: “See to it you tell no one anything, but go and show yourself to the priest and offer what Moses appointed for your cleansing, as a witness to them.”d But he went out, started to preach many things and advertise the word,e so that he was no longer able to come into the city openly, but was out in deserted placesf; and people came to him from everywhere.

Textual Notes, vv. 40-45

a. leper: As mentioned above, leprosy in the Bible is not necessarily the same thing as modern leprosy (a.k.a. Hansen’s disease); however, it may have been in this case. Confusion or uncertainty about the term tsaraȝath seems to have led the translators of the Septuagint to render the word as lepra [λέπρα], meaning “scales” or “scaliness,” a term used chiefly for psoriasis but apparently something of a catch-all for skin disorders.

b. Moved with pity/Impassioned: Here, I shall say boldly that the RSV’s translation—although fairly traditional—is just wrong. I get why they made the choice to translate it that way, because the word that actually occurs seems, in this context, impossibly weird! And I’m not exempting myself from this. I went with a translation that’s defensible (especially etymologically), but certainly debatable and maybe even a tad strained.

See, the term here is orgistheis [ὀργισθεὶς]. That does not mean “moved with pity”; there is a word for that in Greek, eleoumenos [ἐλεούμενος], and it was perfectly familiar to every writer of the New Testament. What orgistheis means is “angered” or “moved with wrath.”

Healing of the Lepers at Capernaum,

James Tissot, 1850

Now, what this means in the context of this miracle, I don’t 100% know. One explanation I’ve heard is that his anger was plain anger, at the tragedy (not at the lepers). This seems to me highly consonant with the other expressions of anger we see from Jesus in all four Gospels. I have also heard the explanation (and it’s a very taking idea, so of course I have absolutely no source to back it up) that this word was used in Greek to describe the whickering of a war-horse before battle.

Most translations, as far as I can tell, conceal the issue by just rendering orgistheis incorrectly—choosing to read what we expect, instead of what is there. I really don’t like this! Scripture is sacred; part of the point of having it is so it can influence and sometimes change our ideas. Why bother if we’re going to do things like this?

c. sent him away at once/put him out right away: The verb here translated “sent away” or “put out” is stronger than this makes it sound; ekabllō [ἐκβάλλω] means “hurl, throw,” and is the same verb Mark has used already to describe Jesus casting out demons. I might have used sent out or even thrown out, except that Jesus then immediately speaks to him, suggesting that he perhaps walked him out (and certainly that the hint of punishment in the phrase “thrown out” is not called for here).

Ruins of a first-century synagogue from Herodion (a settlement

about 7.5 miles south of Jerusalem). Photographed by

Deror Lin; used under a CC BY SA 3.0 license (source).

d. a proof to the people/a witness to them: The RSV’s insertion of “the people” here strikes me as very strange. As far as I can see, it corresponds to nothing in the Greek, which seems merely to be Jesus telling the former leper to give evidence to the priests; that direction aligns with the instructions in Leviticus.

e. to talk freely about it, and to spread the news/preach many things and advertise the word: My penchant for keeping things as literal as possible, and to come as near as I can to “one Greek word = one English word,” motivated this difference in wording. The RSV seems to be interpreting kērüssein polla [κηρύσσειν πολλὰ], literally “herald many things,” by giving polla an adverbial force; as so often, this is not impossible, but also not natural. (Of course, it’s also possible that they simply decided in favor of a more idiomatic English equivalent, which would be perfectly sensible. I’m sacrificing precisely that in order to be just a little bit more literalistic—or perhaps, in the case of angling to use word rather than news, a bit ridiculously literalistic.)

f. the country/deserted places: “Deserted” or “lonely places” is again a word-for-word rendering, and the first word is rather interesting. The adjective erēmos [ἐρῆμος] is in question, and it would be called upon again, approximately three hundred years later, to describe the landscape into which Abba Anthony the Great went alone, seeking God and relief from temptation. (By most accounts, he did find the One, though none pretend that he found the other.) It is for this reason that a solitary monastic was called an eremitic, or, to give the term the form it later took in English, a hermit.

*The Talmud—which is the Mishnah (compiled in the second century), plus a slightly later rabbinic commentary on it called the Gemarah; this dates to either the later fourth century or around the year 500, depending on whether we’re talking about the Jerusalem or Babylonian Talmud, and no, this doesn’t get easier. Anyway, the Talmud lists seven sins that could cause tsaraȝath: slander, murder, theft, perjury, immoral sex, pride, or avarice. Three Biblical victims of the disease were held to exemplify tsaraȝath being imposed as a punishment: Joab, one of David’s champions, for murder (II Samuel 3.12-27ff.); Gehazi, the servant of Elisha the prophet, for avarice (II Kings 5.15-16, 20-27); and Uzziah, the tenth King of Judah and twelfth monarch from the House of David, for pride (II Chronicles 26.3-5, 16-21).

**We do need to qualify this with some “to all appearances,” “more or less,” etc. Obviously Jesus often departed from the opinions of most Pharisees on points both ritual and moral. However, when it comes to both his theological priorities and his politics (or lack thereof), he is unmistakably a Pharisee rather than an Essene, since for all his apocalypticism he has not remained attached to the Temple system and continued to live in mainstream society. He is also a Pharisee rather than a Zealot, in his criticisms of violence and his conspicuously positive attitude toward Roman soldiers, of all people. And he is a Pharisee rather than a Sadducee, as not only the title rabbi suggests (the Sadducees being mainly priests, not teachers), but all of his doctrine: he clearly accepts a wider canon than the Sadducees, he affirms the distinction between body and soul, the immortality of the latter, and the final resurrection of the former; he believes in a multitude of angels (indeed, legions of them at minimum). As far as I can tell, in first-century Palestine, your next option for “how to do a heckin Judaism” was being a Samaritan, which, no; and your next after that was to be … Simon Magus, I guess? Which I imagine some of the authors of the Talmud would find droll. The point is, “Pharisee” is really the only contemporary category Jesus can be made sense of as inhabiting. Of course, once the sect of the Nazarenes arose in his wake, he obviously has ties to that as well; but they are, so to speak, post-contemporary.

†The Midrash Rabbah is a compilation of rabbinic commentaries on the Torah and the Chamesh Megilloth (the “Five Scrolls,” i.e. the Song of Songs, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Esther, which stand together at the beginning of the third section of the Hebrew Bible. The form of the Midrash Rabbah we possess today dates to the sixth century, but is based on older material, some of which goes back to a period before the decision to prefer the Masoretic text (which is known because its commentary occasionally reflects differences in wording from the Masoretic—these differences sometimes align with the Samaritan Torah or the Septuagint instead).

‡Interestingly, this stage (or variety) of tsaraȝath was interpreted by some rabbis as a blessing, albeit not primarily for the sufferer: if a house was going to be properly inspected and cleansed, everything in it had to be taken out first—which of course meant, if it were tsaraȝath for miserliness, that the homeowner would have to bring out any possessions which they had hitherto pretended not to have in order to avoid loaning them to people.