Mark Is a Land Contrasts

Finally getting this out, a mere sixteen days after Mark 1.21-28 was actually used as our Mass Gospel! Hoping to catch up to where we now are by, or perhaps on, Ash Wednesday.

Speaking of Mark: as we’re now in Year B, I recently wrote us a brief intro to this Gospel. However, that was mostly about the provenance and style of the book; it occurred to me only a few days ago that I said next to nothing about Mark’s THEMES. I presented my book report to the class unfinished! That’s illegal, and I’d like to remedy it now.

Mark has several unusual traits among the canonical Gospels. Most of its material also occurs in Matthew, sometimes with identical wording; in other respects, though, it stands out. Here is an incomplete list of things it has that the other three don’t:

- A few unique parables, logia,1 and bits of commentary—e.g. “The sabbath was made for man, not man for the sabbath” (2.27)

- A description of Jesus as “the Son of Mary,” and as having sisters as well as brothers (6.3)

- Explanations of certain Jewish customs, e.g. ritual hand-washing

- Jesus’ exasperation that the disciples remain “slow on the uptake” after the feedings of the five and four thousand (8.14-21)

- Certain words and phrases left out of Matthew and Luke—e.g., only Mark’s account of the greatest commandment opens with the Shema,2 and only Mark records the specific Aramaic words used by Jesus in a few instances3

- Certain chronological distinctions: e.g., only Mark distinguishes the triumphal entry from the cleansing of the Temple, and the blasting of the fig tree from its withering, as occurring on different days (11.1-26)

- The cryptic mention of “a young man having a linen cloth cast about his naked body” in Gethsemane (14.52-53)

- Conflicts in the testimonies against Jesus at his trial (14.55-59)

- Fanfic endings: Mark 16 vv. 9-20 are by another hand, and are known as the Longer Ending, which also features the unique promise that, among the signs accompanying those who believe, “if they drink any deadly thing, it shall not hurt them” (a promise that legend tells us was fulfilled in an attempted assassination of St. John); there is also the Shorter Ending, found in a handful of Greek manuscripts and rather more Ethiopic ones, which reads simply (of the women who “said nothing to anyone, for they were afraid” in 16.8): But they reported briefly to Peter and those with him all that they had been told. And after this, Jesus himself (appeared to them and) sent out by means of them, from east to west, the sacred and imperishable proclamation of eternal salvation.4

Mark also omits a handful of things the other three all include (this list is also incomplete):

- Any allusion to the Nativity (not even something like John’s indirect “Word became flesh” prologue), or to St. Joseph

- Samaritans

- The name of the high priest who presided over Jesus’ trial

- In the oldest and best manuscripts, any direct appearances of Christ after the Resurrection (and indeed all material following 16.8)

Finally, Mark emphasizes certain things that, although present, seem to be of less concern to the other Evangelists:

- The largest proportion of miracles to the rest of the text, particularly exorcisms

- The secrecy of Jesus about his identity and (some of) his miracles

- The longest account of the execution of St. John the Baptist

- Opposition to the doctrines and influence of the Sadducees

- The incomprehension and failure of the disciples

- Striking comments on the interior states of the “characters” in several episodes: e.g., that in dealing with the rich young ruler, “Jesus beholding him loved him” (10.21), or that Peter took notice of the second cock-crow and “when he thought thereon, he wept” (14.72)

Mark 1.21-28, RSV-CE

An ikon of Christ exorcizing the demoniac

in the synagogue at Capernaum (note

the prostrate figure at the bottom), created

in the eleventh century.

And they went into Capernaum; and immediately on the sabbath he entered the synagogue and taught.a And they were astonished at his teaching, for he taught them as one who had authority, and not as the scribes.b And immediately there was in their synagogue a man with an unclean spirit; and he cried out, “What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are, the Holy One of God.”c But Jesus rebuked him, saying, “Be silent, and come out of him!”d And the unclean spirit, convulsinge him and crying with a loud voice, came out of him. And they were all amazed, so that they questioned among themselves, saying, “What is this? A new teaching!f With authority he commands even the unclean spirits, and they obey him.” And at once his fame spread everywhere throughout all the surrounding region of Galilee.

Mark 1.21-28, my translation

And they made their way to Capernaum. And right away he began teaching in the synagogue on sabbaths.a And they were shocked at his teaching, for he was teaching them like someone who has power and not like the scholars.b And right away there was someone in their synagogue in an unclean spirit, and he cried out, saying “What business could you have with us, Jesus Nazarene? Have you come to destroy us? I know who you are, the holy one of God.”c But Jesus rebuked him, saying, “Be muzzled and come out of him.”d And, tearinge him, the unclean spirit gave a great cry and came out of him. And everyone was awed, so they discussed it among themselves, saying: “What is this? A new teaching;f he gives orders with power to unclean spirits, and they listen to him.” And the noise about him everywhere came right away into the whole region of the Galilee.

Textual Notes

a. on the sabbath he entered the synagogue and taught/he began teaching in the synagogue on sabbaths: The verb used in the text here is what’s called an imperfect. This means that it describes an action in the past thought of not as a single, complete act, but as something ongoing or recurring. The most common equivalent to imperfect verbs in English (whose verb system is from one perspective surprisingly poor) is the past progressive form, “was ___ing”; other interpretations include “used to ___” or “kept ___ing.” Translating the imperfect as what’s called a simple past, which is what the RSV has done here, is defensible, but it’s more normal to do for a different form (the aorist). I have preferred an inceptive interpretation of the imperfect here, which means taking it to indicate the beginning of an action, in this case a habitual or repeated action (also called the frequentative sense of the imperfect). I’ve done this for two reasons: first, that this is a sense of the imperfect. Choosing this particular sense of the imperfect is still a judgment call, yes, but I feel it is slightly more grammatically sound than the call made in the RSV. And second, the text does not actually say “on the sabbath,” but “on sabbaths,” tois sabbasin [τοῖς σάββασιν]. This could be a figure of speech, but Mark does use the singular to sabbaton [τὸ σάββατον] in the very next chapter. So, all in all, I think my version is the stronger of the two.

A sofer (a type of Jewish scribe) sewing together

parchments to make a scroll. Ephraim Moses Lilien,

ca. 1895-1925.

b. not as the scribes/not like the scholars: Let’s take a moment and get an idea of what scribes, hoi grammateis [οἱ γραμματεῖς], were, to the peoples of classical antiquity. We take the ability to read and write for granted as the most basic level of education a person can have; most of us are vaguely aware that literacy was a lot less common in past centuries, but we don’t tend to think much about it (save perhaps for the minds behind The Chart and similar jewels of anti-scholarship). Historically, however, being a scribe was a highly respectable and accomplished profession, not unlike teaching at the Ivies today. Sticking to the simple example of literacy, most of us find Hebrew hard to read, even before bringing in vowel pointing, yet scripts like the Hebrew alphabet5 represented a massive simplification of a scribe’s job. The earliest scripts in the Western tradition worked were Egyptian hieroglyphs and the cuneiform of Sumer. Any Egyptian scribe worth hiring would have understood about a thousand hieroglyphs without thinking; an equivalently-skilled Sumerian, around fifteen hundred cuneiform glyphs.6

In Judæa specifically, scribes normally meant scholars of the Torah. They were not necessarily a theological “party” unto themselves, like the Pharisees and Sadducees were; nor were they a type of clergy or a body from whom clergy had to be drawn, like the Levites. They were a profession whose work was naturally connected with all those groups, but distinct—a little like theologians today, who are not the same thing as the priesthood but are closely tied to them.

c. What have you to do with us, Jesus of Nazareth/What business could you have with us, Jesus Nazarene: A maximally-literal rendering here would be “What [is] to us and to you,” i.e. pertains to or concerns both us and you. This was a stock expression. What little research I did suggests that it appeared in Greek from about the second century BC forward, but originated in Hebrew and was recognized as a Semiticism (or at least as a vaguely “foreign” turn of phrase—sort of the way we recognize that “attorneys general” is recognizably odd in English, whether or not we happen to know it’s a survival from Law French). It could be hostile or insolent, but equally served as an idiomatic expression of humility; What does this have to do with me?, with a full range of possible tones, is more or less the idea underlying the multiple senses of the phrase.

d. “Be silent, and come out of him!”/”Be muzzled and come out of him”: Greek actually does have a verb that simply means “to be silent,” but that verb is not used here. In this text, it is phimoō [φιμόω]—some of my readers may have cause to recognize that linguistic stem, though I certainly hope not—which is derived from a noun meaning muzzle or gag. Why the RSV decided against such a vivid term, I can’t say, but I saw no reason to.

e. convulsing/tearing: The verb used here originally meant “tear, rip.” I wasn’t able to find much on the history of the word, so I don’t know whether there was a colloquial or idiomatic sense in which it could mean “convulse”; since tear is a pretty variable word in English, I decided to keep it open-endedly literal.

Note f, “a new teaching”: The House of Shammai and the House of Hillel

“A teaching” here may indicate an interpretive tradition or school of thought, a little like Thomism or Calvinism today. This actually came up in passing in my last post, but only in a footnote (and that post wasn’t part of this series on Mark anyway). Let’s dig into it a little.

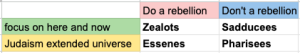

You may be familiar already with four major “parties” of second-Temple Judaism: the Essenes, Pharisees, Sadducees, and Zealots. These groups were about as political as they were theological.7 The Sadducees were straightforward Roman collaborators, and are conflated in the Gospels with “the Herodians,” partisans of the dynasty of the Herods. The Essenes and the Zealots were both in favor of armed revolt against the Roman Empire, though on somewhat different terms. The Essenes and the Pharisees shared an intense concern with knowing, keeping, and commenting upon the Torah; for their part, the Pharisees believed that God would deliver the Jews from Roman dominance if they kept the Torah properly, without any need for armed revolt. Consider, if you will, this horribly cheap-looking and grossly oversimplified chart:

The Houses of Shammai and Hillel were something else, a more strictly doctrinal dispute, internal to the Pharisees. These were schools of halakha, or the application of the Torah to daily life and conduct, both ritual and ethical. Both were named for their founders: Hillel the Elder, who was born in Babylon8 around 70 BC, traveled to Jerusalem at forty years of age, and died around 10 CE9; and Shammai, who was about twenty years Hillel’s junior and died around the same age as well.

The men themselves seem to have had a high opinion of each other,10 but their general outlook and halakha were quite different. Hillel was famous for being lenient, compassionate, and optimistic in his interpretations, and on the whole his rulings prevailed during the Tannaitic period. Shammai was a more severe, rigorist personality; his views enjoyed increasing ascendancy during much of the first century. As a matter of fact, there was a proverb about the two: “The House of Shammai binds; the House of Hillel loosens.” What a crazy coincidence, am I right? (And if you’re wondering: yes, Jesus’ teaching generally does line up much better with Hillel’s—except on the topic of divorce, which is interesting.)

So when the people in Capernaum talk about a “new teaching,” it’s possible that what they’re perceiving Jesus to be founding a new beyt, a new school of interpretation. He tells people not just how the text of Scripture is interpreted by these half-dozen authorities, but, flatly, what the text means—already an audacious move. He then immediately goes on to exorcize a spirit with a very simple verbal command! No incense, no preliminary recitation of key passages of Scripture, no gathering of a minyan11: just “Shut up and get out,” and the spirit obeys him. This is not characteristic of Beyt Hillel or Beyt Shammai. This is weird. And, well, it’s only gonna get weirder, people.

Footnotes

1A logion is a saying, referring most often to sayings attributed specifically to Jesus. Most logia are to be found in the canonical Gospels; a few are found in rival Gospels (e.g. the Gospel of Thomas) or other parts of the New Testament (e.g. St. Paul’s quotation that “It is more blessed to give than to receive” in Acts 20).

2This is the name for the Judaic formula of belief: Shemaȝ Yisçra’el, YHWH ‘Eloheynuw, YHWH ‘echad [שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ יְהוָה אֶחָֽד], or “Hear, O Israel: the LORD our God, the LORD is one.” (A few other variant translations also exist.) It occurs in Deuteronomy 6.4, and is the opening line of a prayer recited twice daily by practicing Jews to this day.

3This includes a few miracles, e.g. Epphatha “Be opened” in the healing of the deaf man (7.34); it may also include the cry from the Cross, “Why hast thou forsaken me?” Matthew’s version, Eli, Eli, lama sabachthani? is the better-known, but Mark represents it as Elōi, Elōi, lema sabachthani? Both versions are Aramaic, drawn from the Targums of Psalm 22. Matthew’s seems to be a little more influenced by the original Hebrew (which would be roughly Ēlī, Ēlī, lāmā ȝazavtānī?), which may indicate that Jesus blended the Hebrew into his Aramaic—he was after all quoting from a psalm—and that Mark, consciously or unconsciously, “corrected” the quotation into a form he perceived as more consistent. But equally, it may mean that Matthew was influenced by the Hebrew independently, and Mark preserves the more exact form of the original cry.

4Both the Longer and Shorter Endings are believed to date from the mid-to-late second century. The Longer Ending can be confirmed by manuscript evidence to have been added by about this time; the scant evidence that survives for the Shorter Ending is later, yet it must have been composed before the Longer Ending became generally known, or there would be no rationale for its composition.

5Yeah, it’s technically an abjad, but consider the following: shut up.

6The reason they required so many symbols is that these systems encoded information much more like modern Chinese than the Hebrew or Latin alphabets. Both systems were descended from pictographs, a sort of quasi-writing that attempted to use pictures to convey meaning—the obvious trouble with that being, how do you depict things that are at all abstract? Simple: you use puns (though you can call it “the rebus principle” if you’re a linguist and don’t want your colleagues to laugh at you). Say we had a system like this, with a glyph like <o> that started out as a pictograph for “eye.” If you used <o> simply to mean “eye,” it would be a logogram, a straightforward glyph for a word. But in another context, <o> might mean the first person singular pronoun, “I,” based on its sound; this makes it a phonogram. In this case, it also happens to be a logogram by coincidence; it would be a phonogram but not a logogram if <o> just represented the sound, e.g. in <o>ξ. (ξ of course represents a hissing sound, because it looks like a snake, so that <o>ξ means “ice,” obviously.) Lastly, <o> could be a determinative: a character representing neither a sound nor a word, but indicating how to interpret another glyph: for instance, say ||| generally means “crowd,” but, since <o> can mean “I” and that’s a pronoun, ||| with <o> written below it as a determinative means “they.” Angry yet? Now imagine every letter is like that. And that you need to know a thousand letters to do something really intellectually demanding like “read the newspaper.” That’s how cuneiform and hieroglyphics worked, and why alphabetic scripts are actually pretty great! Even English spelling is enormously easier than what an ordinary scribe had to deal with in the bronze age.

7Theology and politics were intertwined in Judaism—more so, and more explicitly, than they are for American Christians today. This is partly because Judaism is intimately tied to geographic place, in a degree that Christianity is not: it’s perfectly possible (if undesirable) for the Pope to move his headquarters to Avignon for a few decades, but you can’t just build another Temple some other place than Jerusalem. In consequence, the political control of the land of Canaan and its relationship to other powers is of major religious as well as civic importance.

8Though Cyrus the Great had issued his famous decree permitting aliyah over five hundred years before, a substantial population of Jews had chosen to remain in Mesopotamia, and Babylon was in fact a major center of Jewish learning. It was to this population that the events of the Book of Esther happened (to whatever extent they are historical), and presumably from them that the magoi got the information about Israelite kings that led them to divine one being born when they “saw his star in the east.”

9I have absolutely no proof of this, or even any real evidence for it, but I’m quite tickled by the idea that “the doctors” in Luke 2 could have included Hillel.

10Which is good, because they were colleagues for many years! Hillel became the Nasi (the head, lit. “prince”) of the Sanhedrin in 33 BC, and I gather held the office until his death; Shammai became his Av Beyt Diyn (the second in command, lit. “father of the house of justice”) in 10 BC.

11A minyan is an assembly of at least ten adult Jews (usually only counting males), required for many ritual purposes in Judaism. Which, okay, they’re in a synagogue, he probably doesn’t need to actively gather a minyan anyway—but he doesn’t even ask ten guys to encircle the demoniac or anything.