Why “Groundhog Day” Is Secretly a Catholic Film

Okay, I’m not really going to do one of those. But I do want to talk about Candlemas, which is the feast that falls on yesterday’s date (and whose themes could, maybe, have influenced the observance of Groundhog Day via the German Catholic immigrants who more or less brought it here1). I hesitate to say that Candlemas is an important feast—only one of the Gospels, Luke, so much as mentions it, and no doctrines seem to hang upon it, so to speak.

Yet it is a feast remarkably rich in significance, which is different. As different as importing things is from signifying things. Not to sound Obi-Wan, but: from a certain point of view, the Feast of Candlemas is within itself a précis of both the liturgical year and the whole person and work of Christ.

We can begin with the name of this feast, or rather names. Candlemas is an informal one, used in the English tradition; it’s formed on the same basis as the name Christmas, “Christ’s Mass.” More formally, it is known by two other names: the Purification of the Virgin, and the Presentation of Christ in the Temple. It is the fortieth day after Christmas, and draws the broader cycle of Christmastide to a close.

The Close of Christmastide

Note that, in this section, I’m drawing on pet ideas and interpretations of my own about the liturgy. Please don’t take everything I say as magisterial!

The Christmastide cycle is one of three into which the liturgical year can be divided: one centered on Christmas, one centered on Easter (Paschaltide), and one following Pentecost; these can be thought of as each dealing primarily with one of the three principal mysteries of the faith: the Incarnation, the Redemption, and the Trinity himself.

The Christmastide cycle is kind of like a symphony in three movements. The first is the preparatory, penitential, vigilant season of Advent, with its purple2 vestments and the slowly-waxing light of its wreath, which takes up the three to four weeks preceding Christmas. There follow the days of Twelvetide,3 the highest solemnity of the cycle; and finally Epiphany, a solemn commemoration of our finally moving the statuettes of the Magi all the way up to the rest of the Nativity set. The time from Epiphany to Candlemas, which maintains the themes of the former, is known by a few different titles; “Ordinary Time” is probably the most common, and “time after Epiphany” is on the list there too, though I will venture to point out that those names are both pretty obvious and quite strikingly boring, hence my preference for the rather rare name Epiphanytide, treating Epiphany not only as the solemnity proper but as a sub-season within Christmastide.

Selection from Andrei Rublev’s ikon of the Trinity, written ca. 1408-1425.

Light imagery pervades and unites Christmastide. The principal Gospel for Christmas Day is from John 1: In him was life, and the life was the light of men. And the light shineth in darkness, and the darkness hath not understood it. … No one hath ever seen God; God the Only-begotten, who is in the bosom of the Father, he hath declared him. The glow of the Advent wreath becomes slowly brighter, even as the days do the opposite. Twelvetide begins on the winter solstice, or rather, on the day conventionally deemed the winter solstice during the Roman Imperial period: from 25 December onwards, the day gains ground once more against the night. And epiphany, of course, is a synonym even now for “revelation,” “manifestation,” “vision,” or “enlightenment.” This light is symbolized for us in one of the normal necessities of Christian ritual, lights—which in Western Europe (and her ex-colonies) pre-eminently means candles. Candles are traditionally blessed at this feast (hence the name), which I think forms a lovely closing to the cycle, carrying light forward from the Beginning of the light.

L’Amor Che Move’l Sol’ e l’Altre Stelle4

Epiphany and Candlemas draw together here somewhat, not only as parts of the Christmas cycle, but as two distinct observances that are both intimately tied into a key element of Christianity. The official name “the Presentation of Christ” also hints at it, punning somewhat on the word present to interpret presentation both as “giving, offering” and as “making-now”: the then still future, but imminent, opening of God’s covenant to the Gentiles. Israel remains God’s eldest child, but he will not perpetually be content without the rest, for thou lovest all the things that are, and abhorrest nothing which thou hast made.5

Epiphany does this in a major, visible way. Its complete name is “the Solemnity of the Epiphany of Christ to the Gentiles.” A star appears in heaven, astrologically indicating the birth of a great king—already this has a whiff of Gentility to it, since the study or use of astrology were not things the Jews went in for. And then the people who actually arrive are magi, Persian priests of some type, whose own arts have led them here to the vanquisher of all magic. In a more understated vein, we have St. Simeon appear from the wings. He blesses the Infant as “a light of revelation to the Goyyim, and the glory of thy people Israel.” Both moments, but especially Epiphany, indicate the opening of God’s covenant to Gentiles as Gentiles.

Simeon in the Temple, Rembrandt van Rijn (1631)

For of course it technically was possible to become a Jew, and still is: in other words, one could always enter God’s covenant by ceasing to be a Gentile. Ruth did, for example. One merely has to deal with years of instruction, a more or less total break with one’s old life on every level (religious, social, even dietary), the risk of long-term condescension or suspicion from many of one’s new compatriots, that whole “circumcision” thing for the males, ritual immersion in a mikveh for both sexes, and oh yeah, keeping the six hundred and thirteen commandments of the Torah, in perpetuity. Now, maybe, one can see something of what St. Paul meant when he spoke of the Torah as a “wall of partition” between the Gentiles and the Jews, and spoke so glowingly about the “mystery” of the Gentiles’ welcome.

Make no mistake: in the New Testament’s dispensation it is still, emphatically, “the Lord thy God, which delivered thee out of the hand of the Egyptian”, that these Gentile converts are to be reconciled to. No possibility is countenanced that we “really meant the same thing all along,” or that the rites of Dionysus or Isis6 or Krišna were simply perceptions of God “expressed in our own way.” They might be mixed with such perceptions, for he is not far from each one of us, but the only God is known only by his self-disclosure. Even though the hour cometh when ye shall neither at this mountain nor yet in Jerusalem worship the Father, nonetheless, if the question is raised, salvation is of the Jews and not of the Gentiles (or even of the Samaritans). The renunciation of Ruth remains; Orpah, remember, goes back not only unto her people but unto her gods. But Ruth’s faithfulness is now answered afresh, in the words of Hosea:

And the Lord said to Hosea, “Go, take unto thee a wife of whoredoms and children of whoredoms: for the land hath committed great whoredom, departing from the Lord.” So he went and took Gomer the daughter of Diblaim … [S]he conceived, and bare a son. Then said God, “Call his name Loammi7: for ye are not my people, and I will not be your God. Yet the number of the children of Israel shall be as the sand of the sea, which cannot be measured nor numbered; and it shall come to pass, that in the place where it was said unto them, ‘Ye are not my people,’ there it shall be said unto them, ‘Ye are the sons of the living God.'” —Hosea 1.2-3, 8-10

The Courtesy of Deep Heaven

But let us turn to the other name of this feast, the Purification of the Virgin. Now, long words ending in –tion tend to dull our attention, so it is hardly surprising that it may take a long time for people to realize: that phrase is rather a funny one. What purity, exactly, was the Virgin lacking in?

Herod’s Temple, as depicted in the Holyland Model of Jerusalem,

created in 1962-1966. Photo by Wikimedia contributor Ariely,

used under a Creative Commons Attribution/Share-alike

license 3.0 (source).

Of course, the name actually comes from a ritual requirement of the Torah. Now, I dare say most Christians today find the sacrificial system so intricately set forth in Leviticus to be a little opaque, so it’s worth spending some time on.

Any “discharge” was more or less ritually impure in the Torah, and the blood of a mother’s childbed was no different. After bearing a son, a woman was unclean for seven days, followed by another thirty-three days of lessened impurity, these numbers being doubled for a daughter. After the full forty (or eighty) days had elapsed, she was to bring two sacrifices: a qar’ban ȝolah [קָרְבַּן עוֹלָה], usually translated “burnt offering,” and a qar’ban chaṭa’t [קָרְבַּן חַטָּאת], usually translated “sin offering.” The standard established in Leviticus was to bring a year-old lamb for the first sacrifice and a pigeon or turtledove for the second, though the poor were allowed to replace the lamb with another bird. (We know from Luke 2 that the Holy Family fell into this latter tax bracket, since they bring two turtledoves to the Temple on this feast.)

Burnt offerings were brought for many purposes of both penitence and thanksgiving, and on all sorts of occasions. The sin offering, however, may seem puzzling, since not only is giving birth not a sin, but childlessness is frequently a curse, tragedy, or punishment in the Hebrew Bible. Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, a second-century scholar and one of the most important sources of the Mishnah,8 explained that the sin offering was brought because, in her labor pangs, the woman swore thoughtlessly that she would never sleep with her husband again, but changed her mind after the child was born because of her love for her husband and her delight in their child; she therefore needed to atone for making an invalid vow. This apparent certainty about what any woman had and hadn’t done may strike us as either offensive or hilarious; however, there is a parallel in Deuteronomy 22 that makes me think twice.

If a damsel that is a virgin be betrothed unto an husband, and a man find her in the city, and lie with her; then ye shall bring them both out unto the gate of that city, and ye shall stone them …; the damsel, because she cried not, being in the city; and the man, because he hath humbled his neighbor’s wife: so thou shalt put away evil from among you. But if a man find a betrothed damsel in the field, and the man force her, and lie with her: then the man only that lay with her shall die. But unto the damsel thou shalt do nothing; there is in the damsel no sin worthy of death: … For he found her in the field, and the betrothed damsel cried, and there was none to save her. —Deut. 22.23-27

Note the phrasing there: not that the victim may have cried for help, but that she did do so. The text defies the variety of human behavior and says flatly that she did. Shimon bar Yochai’s explanation of the sin offering here may seem like it applies the same principle the other way, presuming guilt rather than innocence. I find it likelier that it reflects the concern with public honor and good name that is far more prevalent in Semitic societies than broadly Anglo ones, and is present in many parts of Scripture. If every mother brings a sin offering for her broken vow, as matter of course, then the mothers who really did make and break a vow in the way bar Yochai describes are not singled out; they are spared embarrassment in this joyful and very public moment of solemn thanks in the Temple. That, to me, very much calls to mind C. S. Lewis’s phrase, “the courtesy of Deep Heaven.”

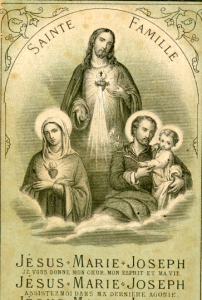

A French holy card to the Holy Family from 1890.

The text at the bottom reads: Jesus, Mary, Joseph,

I give you my heart, my spirit, my life.

Jesus, Mary, Joseph, help me in my last agony.

Here, then, we may see the themes suggested by “the Purification” draw close to those of the Baptism of Christ (a feast called Theophany in the East), as those suggested by “the Presentation” draw close to those of Epiphany. He who needed no baptism is baptized nevertheless, “to fulfill all righteousness”—an example set for him beforehand by his Mother, who swore no rash vow during her labor without pangs (and, according to some traditions, even without blood); and also by his father, who, rather than seek to have (as it seemed to him) his treacherous bride stoned or even subjected to public disgrace, “was minded to divorce her quietly.” The delicacy here, the tenderness, the desire to spare the beloved even the smallest pain—words fail me.

He Comes With a Sword

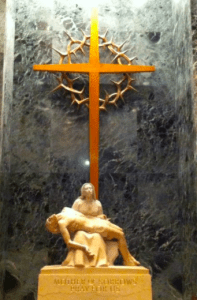

Lastly, Candlemas is what we could call a cardinal feast, in that cardinal comes from the Latin word for “hinge” or “pivot.” (The other two cardinal feasts, on the three-cycle year I proposed above, would presumably be: Pentecost, which concludes the Easter season and in whose light we live today; and Christ the King, which by invoking the Parousia9 also helps us turn our minds to the first coming.) We would in any case be turning soon to our preparation for Easter, i.e. Lent; the fact that Candlemas commemorates St. Simeon gives us a concrete locus for doing so in the text of the Gospel itself.

There was a man in Jerusalem, whose name was Simeon; and the same man was just and devout, waiting for the consolation of Israel: and the Holy Ghost was upon him. And it was revealed unto him by the Holy Ghost, that he should not see death, before he had seen the Lord’s Christ. And he came by the Spirit into the temple: and when the parents brought in the child Jesus, to do for him after the custom of the law, then took he him up in his arms, and blessed God, and said, “Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word: for mine eyes have seen thy salvation, which thou hast prepared before the face of all people; a light to lighten the Gentiles, and the glory of thy people Israel.” And Joseph and his mother marvelled at those things which were spoken of him. And Simeon blessed them, and said unto Mary his mother, “Behold, this child is set for the fall and rising again of many in Israel; and for a sign which shall be spoken against; (yea, a sword shall pierce through thy own soul also,) that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed.” —Luke 2.25-35

Verses 29 to 34 are recited daily by Catholic priests and religious, as an element of the last prayers said before bed, under the Latin title Nunc Dimittis. Simeon’s mention of this sign which shall be spoken against (sometimes rendered “a sign of contradiction”) and that a sword shall pierce through thy own soul turn our attention immediately to the Passion, and especially to the Virgin herself, standing at the foot of the Cross.

T. S. Eliot, not long after his conversion, was asked to contribute to a series of pamphlets called Ariel Poems, for use in Christmas cards and letters. (Why “Ariel,” I don’t know, unless it was in reference to Ariel as a rare poetic name for Jerusalem; the name means “lion of God.”) He assented; the result was one of my personal favorites of his, “A Song for Simeon.” I close with a selection from it.

Before the time of cords and scourges and lamentation

Grant us thy peace.

Before the stations of the mountain of desolation,

Before the certain hour of maternal sorrow,

Now at this birth season of decease,

Let the Infant, the still unspeaking and unspoken Word,

Grant Israel’s consolation

To one who has eighty years and no to-morrow.

According to thy word.

They shall praise Thee and suffer in every generation

With glory and derision,

Light upon light, mounting the saints’ stair.

Not for me the martyrdom, the ecstasy of thought and prayer,

Not for me the ultimate vision.

Grant me thy peace.

(And a sword shall pierce thy heart,

Thine also).

Footnotes

1The influence of central European immigrants, principally Germans, is why Groundhog Day is a thing in the US but (I understand) not in the British Isles.

2Probably. Rose vestments are of course permitted for the Third Sunday of Advent; and, while it is exceedingly rare outside Spanish-speaking countries, some places have what is called the cerulean privilege, permitting the use of blue vestments (otherwise unknown to the Latin rite) either for the season of Advent or for Marian feats, usually the latter I believe.

3This period is so named because it formerly consisted in twelve days, 25 Dec.-5 Jan. Since Epiphany has in most places been pegged to the nearest convenient Sunday to 6 January rather than kept on 6th January regardless, Twelvetide now varies in length from eight to fourteen days.

4This is the last line of Dante’s Paradiso, and means ” the love that moves the sun and the other stars”; this reference to their motion is an important element not only in Dante’s physics, but in the philosophy of causality and even of space-time. The love he alludes to here is the love of God only a perfected creature could have.

5Wisdom of Solomon 11.24.

6Apparently the native Egyptian name for this goddess was ?ūsat, ? representing a character I’ve never even seen before—which, I’m sufficiently fond of weird alphabets to find that surprising—and therefore haven’t a clue how to transliterate. As Will Cuppy wrote of the standard Hellenistic name for Khufu (the pharaoh who is supposed to have built the Great Pyramid), “How the Greeks made Cheops out of Hwfw is at present unknown.”

7The name Loammi (or Lo-Ammi in some versions) literally means “not my people.” In a non-prophetic context, it would be understood essentially as labeling the child a bastard. That is true here also, but with the added layer of deliberate symbolism that God has required of Hosea, effecting his own cuckoldry by his marriage to Gomer as the Lord has endured being cuckolded by Israel’s pursuit of other gods.

8The Mishnah is a compendium of the Oral Torah, the tradition according to which the Pharisees interpreted and applied the Written Torah (this latter being often referred to simply as “the Torah”). It now forms the first part of the Talmud: its second and much longer part, the Gemara, is a commentary on the Mishnah. The Mishnah was composed during what is called the Tannaitic period, named for the Tannaim or “repeaters,” the early rabbis. Roman persecutions of Judaism, prompted in part by the Jewish Wars of 66-73 and 132-135 (of which the destruction of the Second Temple was only the worst of several major disasters for the Jews), prompted them to write down the Oral Torah lest it be lost. The Tannaitic period lasted from about the year 10 to 220, and it is therefore probable that the Mishnah represents, not exactly but quite closely, the Oral Torah Jesus would have been raised with. Exactly what authority Christians ought to give the contents of the Mishnah on these grounds is less clear. On the one hand, Jesus firmly condemns the practice of “teaching as doctrines the commandments of men” on several occasions; yet in Matthew 23, in the very preface of the Seven Woes, he also says of the Tannaim that they “sit in Moses’ seat: all therefore whatsoever they bid you observe, that observe and do”.

9The Parousia is a Greek term for the Second Coming; I like it rather better than the English, because I find it more vivid: what it literally means is “drawing near, visitation,” and it was used to denote a royal visit paid in honor to a city.