The Gospel for the What Now?

This post continues the topic from my last, i.e. the Gospel of Mark, and more particularly the bits of it read on most Sundays of January 2024. Due to other assignments I am a bit behind—I’m hoping to catch up by getting this post and my next published before the end of the month.

The 21st was the Sunday of the Word of God. This is quite a new observance. Pope Francis established it in 2019, with the letter Aperuit Illis: the title is an allusion to the Latin text of Luke 24.45, which says that Christ “opened the Scriptures to them” (the them in this case being the two disciples who had been traveling to Emmaus); it always falls on the third Sunday in Ordinary Time.* The notion is to devote the day to the study and honor of sacred Scripture, with the ritual and practical details being left to bishops’ conferences and the faithful. (I’d quite like to see us institute a rite of formal veneration, such as presenting the Book of the Gospels to the faithful during or after Mass to be reverenced with a kiss, à la the honor paid to most relics.)

Funnily enough, it was today’s Gospel (I am writing this on the night of the 28th) that offers a more obvious link to the theme of that day, since it has Jesus teaching in the Capernaum synagogue. On the other hand, I suppose it’s strictly impossible for a Biblical passage to be “the wrong one” for the Sunday of the Word of God! Anyway, let’s jump into Mark. We are not starting quite at the beginning here; the ministry of St. John the Baptist has been briefly recounted, as have Jesus’ own baptism and temptation in the wilderness. We pick up from there.

Mark 1.14-20, RSV-CE

Selection of a view from Ari Mountain in Upper Galilee,

northwest of Capernaum. (Taken by user Someone35 and

used under a Creative Commons Attribution Share-alike 3.0 license—source.)

Now after John was arrested,1 Jesus came into Galilee,2 preaching the gospel3 of God, and saying, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God4 is at hand; repent,5 and believe in the gospel.” And passing along by the Sea of Galilee, he saw Simon and Andrew the brother of Simon casting a net in the sea; for they were fishermen. And Jesus said to them, “Follow me and I will make you become6 fishers of men.” And immediately they left their nets and followed him. And going on a little farther, he saw James7 the son of Zebedee and John his brother, who were in their boat mending the nets. And immediately he called them; and they left their father Zebedee in the boat with the hired servants,8 and followed him.

Mark 1.14-20, my translation

After John had been handed over,1 Jesus came into Galilee,2 proclaiming the good news3 of God and saying that “The time is fulfilled and the kingship of God4 is near: change your minds5 and believe in the good news.” And while he was walking by the Sea of Galilee, he saw Simon, and Andrew, Simon’s brother, casting in the sea, as they were fishers; and Jesus said to them: “Come after me, and I will make you into6 fishers for people.” And right away they left their nets and followed him. And going on a little, he saw Jacob7 son of Zebadiah with John his brother (they were in the boat mending their nets), and right away he called to them. And leaving their father Zebadiah in the boat with the hired help,8 they came after him.

Textual Notes

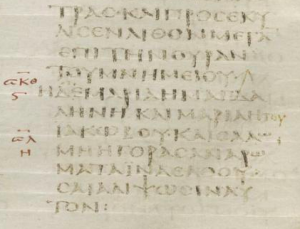

A passage from the end of Mark 15 in the Codex

Sinaiticus, an important mid-fourth century

manuscript of the Bible (also contains the Shepherd

of Hermas and the Epistle of Barnabas).

01. arrested/handed over: Like English, Greek uses a lot of verbs that come compounded or paired with prepositions; sometimes these specify the object of the verb, other times they change its meaning. (Think of how look out as a verb, lookout and outlook as nouns, and look out! as a command all relate to each other.) The RSV’s “arrested” and my “handed over” here both translate a form of the verb paradidōmi [παραδίδωμι]. Very literally, it means “to give to,” but that naturally gets applied in a lot of situations; to hand (or turn) something or someone over to the authorities is a set phrase in English, so I opted for this as being a little more literal than “arrested.” (Paradidōmi also happens to be the most usual verb for describing what Judas did on the night of the Passion.)

2. Galilee: You may, rarely, come across sources which call this region “the Galilee” instead of simply “Galilee.” Apparently, this is because the name comes from the Hebrew term galiyl [גָּלִיל], meaning “cylinder” or “wheel,” because the region is roughly circular (bound by the Jezreel and Jordan valleys to its south and southeast, the Sea of Galilee to its east, and the Lebanese highlands to the north).

3. gospel/good news: I gather it’s more or less common knowledge that the translation “gospel” for euangelion [εὐαγγέλιον] is quite correct, or at least that it is quite correct as long as you’re speaking Anglo-Saxon! The older form of the English word is godspel, “good news.” The modern term spell (both in the sense of “to cast a ___” and that of “___ this word”) comes from an ancient Indo-European word simply meaning “to talk, say, speak.”

The history of the Greek word is its own interesting detour. In antiquity as much as the present day, news is usually bad; the specifying prefix eu- [εὐ-], meaning “good” or “well” (also seen in words like eulogy and euphemism), was thus an important modification in any case. But euangelion had been coined some time before this, and was old enough to have acquired additional senses by the first century. In the singular, it could by extension mean a tip given as thanks to a messenger who had brought the good news in question; however, the plural form euangelia [εὐαγγέλια] had a religious meaning—that of a thank-offering sacrificed to the gods in gratitude for the news. (Another term for thank-offerings in Greek, it so happens, is eucharistia [εὐχαριστία]).

The temple of Augustus and Livia (his wife) in Vienne, France.

Photographed by Jacques Mossot in 2013, and used

under a Creative Commons Attribution Share-alike 4.0 license (source).

But euangelion also had a political meaning. It’s rarely appreciated today what the Roman emperors, for lack of a better word, meant to the populace of the Empire. We tend to associate the term “Roman emperor” with things like the deadly lunacy of Caligula or Nero’s persecution of Christians. But remember, these were not the makers of the imperial office: they were coasting on political capital earned by other people, above all by Julius Cæsar and his heir Augustus. The emperors were popular! Augustus especially: his victory at the Battle of Actium in 31 BC established peace in the Mediterranean for the first time in two hundred years;** one of the customary titles for the Roman emperor was sōtēr [σωτήρ], which means both “savior” and “healer” in Greek; there are reasons these men were deified, and why participation in the imperial cult† was considered a useful test of loyalty to the scepter. The imperial cult was particularly important in the wholly or partly Greek cities of Asia Minor—places like Ephesus, Pergamon, and Sardis—and in one of them, Priene, a proposal was made to date the city’s calendar from Augustus’s birthday as its new year’s day, in honor of the euangelion of the emperor’s birth.

4. kingdom of God/kingship of God: I’d like to make two points about this phrase. First, it’s rather striking that Mark uses the phrase “kingdom of God” in contrast to Matthew’s “kingdom of heaven.” There is, of course, a very stern prohibition against taking the Lord’s name “in vain; for the LORD will not hold him guiltless that taketh his name in vain.” (This likely indicates swearing false oaths or making false vows; oaths and vows are not a big part of daily life in the modern world, but their role in history is very nicely explained by my favorite Tolkien YouTuber, Girl Next Gondor.) For this reason, as time went on, to pronounce the divine name at all became increasingly taboo in Jewish culture; by Jesus’ time, it was only meant to be pronounced by one Jew, in one place, one time per year—that Jew being the high priest, that place the Holy of Holies (the innermost court of the Temple), and that time being the incense offering on Yom Kippur, the Day of Atonement.

The title ‘adownaiy [אֲדוֹנָי] (mostly transliterated adonai), or “my lord,” commonly replaced the Tetragrammaton both in spontaneous prayer and with lectors or cantors reading or chanting liturgical texts. Other customs are also observed—perhaps because ‘adownaiy does occur “in its own right” in many places in the Hebrew Bible. It’s common practice among Jews to refer to God as ha-Šem/ha-Shem [הַשֵּׁם], or literally “the Name.” It’s thought that Matthew—which, whether it was the first Gospel written or not, was certainly addressed to a Judaic milieu—uses the phrase kingdom of heaven rather than kingdom of God out of sensitivity to the reverence surrounding the name, which indeed he probably shared.

The fact that Mark does not do this is thus attention-grabbing, especially if he really did write after Matthew and intend more or less summarize his work (a view I’m disposed to accept, though it’s far from crucial). It would seem to lend some small support the notion that the Gospel of Mark was not addressed to Jews: if the mainstream view that Mark was the first Gospel is correct, this may imply in turn that the mission to the Gentiles was earlier and/or more substantial than is sometimes thought. Alternatively, this could be an artifact of the purpose of Mark, and may reflect a desire to maintain Jesus’ words as exactly as he could recall.

Finally, on the kingdom/kingship distinction I’ve made here. In English, when we hear the word “kingdom,” I think the territorial sense is foremost in most of our minds, as distinct from the office of kingship. The same was not necessarily true of the Greek word basileia [βασιλεία]; its center of gravity was more in the office, the sovereignty, rather than the domain. Thus, a phrase like “the kingdom of heaven” somewhat inclines us to imagine the holy city, new Jerusalem, coming down from God out of heaven, prepared as a bride adorned for her husband, in an almost cartoonish way—as if it were simply going to be the new top layer of the earth’s crust now. The Greek (I can’t speak for whatever the Aramaic may have been) sends a different message, one better understood as a state of affairs than as a place. The reign of God, the rule of God, these phrases are more in line with the drift of the Biblical text we possess.

5. repent/change your minds: The verb used here, metanoeō, is constructed from the prefix meta [μετα] “after, next,” and the verb noeō [νοέω] “to observe, see, notice; to think, suppose, plan.” The common Orthodox name for both the sacrament of penance, metanoia, is from this same root; and metanoeō itself means (in its constituent elements) “to think again, rethink, have second thoughts.” It’s also worth pointing out that, at this period and throughout much of human history the heart was hel the organ of thought, not the brain.

6. make you become/make you into: Here, I have departed slightly from literalism (which the RSV here retains) in favor of a more natural English idiom. The most literal rendering would be “I shall make you to become,” which is comprehensible English but not something a person would ever say.

7. James … Zebedee/Jacob … Zebadiah: The Hebrew original of the name James was Yaȝaqhov [יַעֲקֹב],‡ the name of the third great patriarch and grandson of Abraham; given that these two names have no sounds in common, this may seem strange! The reason for this is it that entered Greek as Iakōbos [Ἰάκωβος], as Greek had no v-sound at the time (or at least no letter for it). From Iakōbos, some Latin pronunciations softened the b to an m, producing Iacomus (later spelled Jacomus). It is from this adaptation of the name that the English versions of the name, e.g. James, are derived.

St. James the Apostle [i.e. “the Greater”],

Peter Paul Rubens, 1612-1613.

The names “John” and “Zebedee” likewise came to English through Greek (Iōannēs [Ἰωάννης] and Zebedaios [Ζεβεδαῖος]), from Hebrew (Y’howkhanan [יְהוֹחָנָן] and Zevad’yah [זְבַדְיָה]), and the latter is a variant of the name Zebadiah, as in the prophet. In the name of keeping names as consistent as possible between the New and Old Testaments—which produces definite literary and theological effects, I have “restored” Jacob and Zebadiah to their role in this story. Since John, to the best of my recollection, neither has Old Testament precedent nor an alternative English form that is any closer even to Iōannēs, let alone Y’howkhanan, I decided to leave that name alone. (The nearest parallel would be Johan, which is used in a number of Germanic languages; but, crucially, it is perceived and treated as a foreign name in English.)

8. hired servants/hired help: The word “servants” in the New Testament is frequently a euphemism—on the translators’ part—for slaves. Slavery in classical antiquity was a rather different thing than it was in American history; however, the differences need not detain us, because the text here does not indicate either slaves or servants, but, well, hired help—a subclass of the working poor, which one is almost tempted to translate as “the hourlies”; they were in a fit state to work, but had few options aside from menial labor 8 such as construction on public works).

*This name is, naturally, much jested over (like many things printed in missals, including the word missal). It is an odd, and arguably just wrong, translation of the concept underlying the title: that these are Sundays which are identified ordinally, i.e numerically. But that really isn’t a sense borne by the English word “ordinary” … ever, in no small part because we have the term ordinal for that. So, I’m calling this one a swing-and-a-miss on the part of the ICEL.

**This is what’s referred to as the pax Romana. Augustus achieved it to some extent by practically but not legally abolishing the Republic; the past hundred years’ many civil wars and revolts had on the whole aimed at taking control of the Republic, but frankly abolishing it might have provoked yet another war. The pax Romana is conventionally held to have lasted for two hundred years, ending around the death of Marcus Aurelius. The concept is not without weaknesses. Right in the middle, in the year 66, the First Jewish War broke out (the one in which the Second Temple was destroyed), inaugurating a series of conflicts that did not cease until the Bar Kochba Revolt was crushed in 135; this is to say nothing of the succession crisis of 69 (“the Year of the Four Emperors”), Trajan’s campaign against Parthia, or Aurelius’s own wars in Germania. However, these were for the most part in far-flung areas of the Empire, so they are not consistently viewed as cause to truncate or drop the idea of the pax Romana.

†Cult here is used in the technical sense employed by scholars of religion, anthropology, etc.: a system of devotional behaviors intended to show honor to some being, generally a deity or auxiliary spirit, such as a saint or bodhisattva; the term used in this sense is not derogatory. (Of course, a person might use it as a neutral description and also, separately, look down on its practitioners, in much the same way that a person might say something like Scientology’s problem is not that it is not a religion, but that it is a very silly religion.)

‡Yes, I did use the letter ȝ (called yoȝ, or yogh—capital form Ȝ) to transcribe the letter ȝayin, and not only because a reversed apostrophe would be indistinguishable from an ordinary one in this low-serif font. I’m afraid you’ll just have to take me to court over that.