Set Your Mind on Things Above

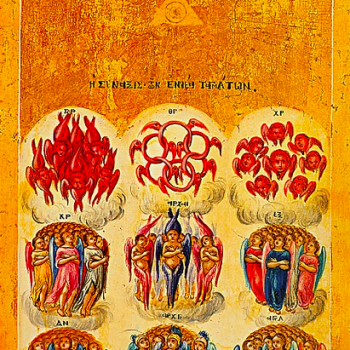

Belarusian ikon of Pentecost, c. 1500. Photo

by Wikimedia user Khomielka, used under

a CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Two distinct Gospels are prescribed for this solemnity: one for the vigil (from John 7, set during the festival of Sukkot) and one for the day proper (from John 20, immediately following the Resurrection). Since both are quite short, only totaling eight verses together, I’m doing both. However, to introduce them, I want to talk a little about what I think is an under-discussed aspect of John: its ties to the Judaic liturgical year.1 To understand that, let’s look briefly at the calendar as such.

We use a solar calendar (the Gregorian), which tracks the orbit of the Earth around the Sun more or less directly.2 Hoever, the Hebrew calendar is a lunisolar calendar. Instead of measuring the solar year directly, it approximates solar years to the nearest lunar month, using both the sun and the moon to tell time (hence “lunisolar,” from the Latin names of the moon and sun, lūna and sōl). Many ancient societies used calendars of this type.

This decision was not made at random. Remember, there was no electric light except lightning, back when any calendar now in use was first invented. The only nighttime illumination you had came from one of four sources:

- the moon (if it’s up at the time, and full enough, and the sky isn’t overcast);

- the stars (again as long as it’s not overcast);

- any freaky bioluminescent stuff (if you brought this, which, no you didn’t, stop lying); and

- fire, if you had a torch or a lamp (which might run out of fuel or wick, or get blown out by the wind).

Photo of a waxing crescent moon over Kingman,

AZ. Taken by Beth Woodrum, and used under

a CC BY 2.0 license (source).

There’s a real sense in which light and time were the same thing, or two aspects of the same thing, in the ancient world. This is set up all the way back in Genesis 1:14-18, which describes the heavenly luminaries as meant by God to tell time:

And God said, Let there be lights in the firmament of the heaven to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs, and for seasons, and for days, and years: and let them be for lights in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth: and it was so. And God made two great lights; the greater light to rule the day, and the lesser light to rule the night: he made the stars also. And God set them in the firmament of the heaven to give light upon the earth, and to rule over the day and over the night, and to divide the light from the darkness: and God saw that it was good.

To Everything There Is a Season

The name Pentecost, from πεντηκοστή [pentēkostē] or “fiftieth,” was already in use as the Greek name for Shavuot, or the Feast of Weeks, fifty days after Passover. Shavuot isn’t a feast we talk about a lot in Christianity; other than the sabbath and Passover itself, the only feasts I’ve heard mentioned in any theological context by most Christians are Yom Kippur and Chanukkah. So let’s talk about Shavuot. In fact, let’s briefly sketch the whole calendar familiar to Jesus and the primitive Church. (If that sounds dumb and boring to you, then … I don’t know why you’re reading this blog, I am always like this! But if you’re specifically interested just in the Scripture, you can scroll down to the heading “Pentecost,” right above the picture of the yellow ears of wheat against a blue sky.)

For religious purposes, the Jewish calendar starts the year with Nisan, the month of Passover and the spring equinox. Its twelve thirteen twelve-y months are as follows. The month names were derived from foreign prestige languages, not unlike the dependence of our month-names on Latin. This mainly meant Akkadian, a Semitic tongue, but also Sumerian (Akkadian’s own prestige language). Each Hebrew month is listed (in Roman and then Aramaic script), followed by its standard number of days, the month’s nearest Gregorian equivalent (none are exact), and finally the source of the name.

Nisan [נִיסָן], 30 days, ≈March; from Sumerian nisag, “first fruits”

Iyar [אִיָּר], 29 days, ≈April; from Akkadian ayari, “blossom”

Sivan [סִיוָן], 30 days, ≈May; from Akkadian simānu “season”

Tammuz [תַּמּוּז], 29 days, ≈June; from Sumerian Dumuzi(d), the name of a god

Av [אָב], 30 days, ≈July; possibly from Sumerian Abu, the name of a god, or Akkadian ‘abū, “reed”

Elul [אֱלוּל], 29 days, ≈August; from Akkadian elūlu, “harvest”

Tishrei [תִּשְׁרֵי], 30 days, ≈September; from Akkadian tašrītu, “beginning”

Cheshvan [חֶשְׁוָן], 29 days; ≈October; from Akkadian waraḥsamnu, “eighth month”

Kislev [כִּסְלֵו], 30 days, ≈November; from Akkadian kislimu, “to thicken”

Tevet [טֵבֵת], 29 days, ≈December; from Akkadian thebetum, “muddy”

Shevat [שְׁבָט], 30 days, ≈January; from Akkadian šapāthum, “to judge”

Adar (Aleph or Rishon) [א׳ אֲדָר], 30 days (appeared in leap years only)

Adar (Beth or Sheni) [ב׳ אֲדָר], 29 days, ≈February; from Akkadian addaru(m), meaning unknown

I Must Be in My Father’s House

Since the time of Jesus, several holidays have gained or lost in importance in Judaism, and new ones have been instituted. This is often due to the destruction of the Temple, which modified or effectively suspended quite a number of commandments in the Torah, but there are other causes as well. (A festival in Iyar, Lag Ba’Omer, commemorates Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai, who lived in the second century; this holiday naturally did not exist in the first century!)

Model of the Second Temple. Used under a

CC BY-SA 3.0 license (source).

Another major change was to the pilgrimage feasts. These were three holidays on which Jewish males were obliged to visit Jerusalem while the Temple stood. (One of the disputes between rabbinic Jews and Samaritans is that Samaritans believe that Mount Gerizim rather than Jerusalem is the appropriate site of these pilgrimages.) I gather this rule applied strictly only to those who actually lived in the Holy Land. For example, we know that there was a Jewish community in Rome, but it took close to a month to travel from Rome to Jerusalem, going by sea for speed and assuming ideal conditions. There could hardly have been permanent Jewish settlements outside the Holy Land if they had to go there once in fall and twice in spring!

In any event, here is the Second-Temple Jewish liturgical year as far as I understand it (do keep in mind that’s a serious proviso).3

1 Nisan. Rosh Chodesh Nisan (First of Nisan), feast—the religious new year (typically mid/late March)

14, 15-21 Nisan. Pesach (Passover) and Matzot (Unleavened Bread), pilgrimage feast—commemoration of the Tenth Plague and the Exodus (typically early April)

22 Nisan-5 Sivan. Sefirat ha-Omer (Counting of the Sheaf; often called “counting of the Omer,” untranslated, in English), season of feasting?*—commemoration of the journey from the Red Sea to Sinai (typically most of April and May)

6 Sivan. Shavuot (Weeks), pilgrimage feast—commemoration of the arrival at Sinai and giving of the Torah (typically late May/early June)

1 Tishrei. Rosh ha-Shanah (First of the Year), fast—preparation for Yom Kippur begins (typically mid/late September)

1-10 Tishrei. Aseret Yemei Teshuva (Ten Days of Repentance), season of fasting—reflection, prayer, and almsgiving before Yom Kippur (typically mid/late September)

10 Tishrei. Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), fast—sin offering by the high priest on behalf of all Israel (typically late September)

15-21, 22 Tishrei. Sukkot (Tabernacles) and Shemini Atzeret** (Eighth [Day] of Assembly), pilgrimage feast—commemoration of God’s mercy during the forty years in the wilderness (typically early October)

25 Kislev-3 Tevet. Chanukkah (Dedication), feast†—rededication of the Temple by the Maccabees (typically mid/late December)

10 Tevet. Asarah b’-Tevet (Tenth of Tevet), fast—commemoration of the siege and destruction of Jerusalem by Nebuchadnezzar (typically late December)

15 Shevat. Tu bi-Sh’vat (Fifteenth of Shevat), feast—”the trees’ new year,” i.e. the beginning of the agricultural cycle for tree-crops, e.g. almonds, dates, figs, pomegranates (typically early January)

13 Adar (Adar II in leap years). Ta’anit Esther (Fast of Esther), fast—commemoration of Esther’s fast before approaching Ahasuerus‡ (typically late February/early March)

14 and/or 15 Adar (Adar II in leap years). Purim (Lots), feast—commemoration of Esther’s deliverance of the Jews from Haman (typically early March)

*I am very much guessing here: the meaning of the celebration in question seems to me to make feasting more natural than fasting. However, 1. I could be wrong, and 2. it is in any case possible that this period could have turned into an occasion of mourning, especially after the year 70. According to one tradition, twenty-four thousand pupils of Rabbi Akiva (a major contributor to the Talmud) were put to death in or after the Third Jewish War of 132-136, during the counting of the Omer; many subsequent pogroms have fallen in this period, and Yom ha-Shoah, Holocaust Remembrance Day, is normally held on 27 Nisan.

**This may have been combined, as it is in Israel today, with the celebration of Simchat Torah (“celebration of the Torah”), which concludes and restarts the cycle of Torah readings; however, I was unable to find out when Simchat Torah began to be observed.

†This is now a minor feast, and is well-known in the US largely due to its treatment as a Jewish analogue for Christmas (an association many Jews find distasteful); at the time, it may have had more importance, as the Temple was still standing.

‡The identity of Ahasuerus is debated. The Septuagint identifies him with Artaxerxes, as do the Esther Rabbah, Josephus, and other ancient sources. 19th- and 20th-cent. scholarship have largely favored an identification with Xerxes I, Artaxerxes’ father (the one who invaded Greece in 480 BC).

Pesach and Yom Kippur were (I gather) the most important of the bunch. Pesach, together with Matzot, commemorated the Exodus, the identity-defining event of Israel’s history. Yom Kippur was the one day on which the high priest passed the Veil in the Temple: following an intricate pattern of sacrifices and ritual cleansings, he offered incense within the Holy of Holies, pronounced the Tetragrammaton, and sprinkled the blood of multiple sacrifices within the Holy of Holies, before the place where the Ark had once rested.4

Thirty Days Hath September, Twenty More Hath the Omer

And now we come back to the third pilgrimage feast, Shavuot, which in English simply means “weeks.” This feast was fifty days after Passover—seven weeks, or a week of weeks, probably the reason for the name. At least some authorities classify Shavuot as a part of, or a completion of, Passover and the Feast of Unleavened Bread. This tracks agriculturally: the two feasts correspond to two grain harvests, the first to that of barley and the second to that of wheat.

To this day, barley and wheat are two of the most important cereal crops in the world.5 Of the two, barley ripens more rapidly, but it is also slightly coarser and has a lower protein content, making it much cheaper (the fact that the child in John 6 is specifically mentioned to have five barley loaves with him suggests, as does the miracle itself, that this is a poor group of people); barley might even be used as animal feed.

Wheat, as the timing of Shavuot suggests, ripens over a slightly longer period, and its flour makes finer, more expensive bread. The period between Passover and the Feast of Weeks is known as the “counting of the Omer,” the sheaf-offering prescribed in Leviticus. The practice of counting this period, out loud—which is considered ritually important to this day—fits into a detail we sometimes miss in Exodus: that Moses, from the beginning, was haggling with Pharaoh for the Israelites to go into the wilderness in order to hold a feast and worship. When Pharaoh finally did let the people go, they had, from Moses, some idea of where they were going and when they would get there. At least one sixteenth-century rabbi6 interpreted the difference between the barley of Pesach and the wheat of Shavuot allegorically, saying that when the Israelites had just escaped from Egypt, they had been tormented into a half-bestial condition, and the progress of counting the Omer brought them into a fit state to receive the Torah when they reached Mount Sinai.

“Lo, This One Was Born in Her”

It’s also interesting to note the appointed lectionary for Shavuot.7 Five short books are grouped together in the Jewish arrangement of the Bible, and each one is read on an appropriate festival: the Song of Solomon, Ruth, Lamentations, Ecclesiastes, and Esther. Passover features the Song of Solomon; Lamentations is now read on Tisha b’Av8; Ecclesiastes is read during Sukkot9; and Esther, naturally, is read for Purim.

Shavuot features the book of Ruth. On one level, this is obvious: Ruth gleaning from the wheat fields of Boaz is a plot point, ergo this book goes with the festival that lines up with the wheat harvest. Besides being a sweet little romance of a book (which forms an interesting complement to the Song of Solomon being read for Passover!), it also communicates part of the genealogy of the House of David—which it connects with two Gentile women: first Rahab, the mother of Boaz, and of course Ruth herself,10 David’s great-grandmother. The inclusion of Gentiles among the people of Israel is the point of the book of Ruth; it is arguably the point of the book of Acts, too, which opens just ten days before Shavuot.

Entreat me not to leave thee,

Nor send me from thy side:

For where thou goest, I will go,

And with thee will abide.

Thy people shall be mine own, yea,

And thy God be my Lord;

Thy death be my grave also,

There may I be interred!

The Lord bring down his judgment unto me,

If anything but death part me from thee.

—Ruth 1.16-17

I’m not sure why Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld,

who painted Ruth in Boaz’s Field here in 1828,

decided to give her such an “ain’t got time for

this shit” expression, but there it is.

“Sheep Not of This Fold”

There is, hidden away, a connection with the Gospel of John here, too. See, even though Matthew has a reputation as being “the Jewish one” out of the four Gospels, John has as good or even a better claim to the title; it is intimately woven with Jewish Scripture and liturgy throughout, not excepting the two passages for Pentecost. Based both on this and a handful of other details (like the beloved disciple being “known to the high priest”), I’m strongly inclined to think that the author of the Fourth Gospel had some kind of family tie to the Zadokites, the clan from which the high priests were selected. The discourses and miracles of John are, in fact, all tied to the various festivals of the Judaic year, timed according to three celebrations of Pesach: one when Jesus was visited by Nicodemus (ch. 3), one near the feeding of the five thousand (ch. 6), and one in which “the lamb of God took away the sins of the world” (chs. 11-20).

What about Shavuot? I believe we find an almost direct reference to it here:

Say not ye, “There are yet four months, and then cometh harvest?” behold, I say unto you, lift up your eyes, and look on the fields; for they are white already to harvest. And he that reapeth receiveth wages, and gathereth fruit unto life eternal: that both he that soweth and he that reapeth may rejoice together. And herein is that saying true, “One soweth, and another reapeth.” I sent you to reap that whereon ye bestowed no labor: other men labored, and ye are entered into their labors. —John 4.35-38

Detail of an illuminated capital from

a 14th-cent. manuscript, now housed

at the National Library of Wales.

The statement that “There are yet four months, and then cometh harvest” presumably means that this episode actually took place in Kislev or Shevat, those being four months before the barley and wheat harvests respectively. (My money’s on Kislev, since we know from ch. 10 that Jesus at least sometimes visited Jerusalem for Chanukkah as well as for the pilgrimage feasts.) However, the language of harvest is plainly associating it with one or both of the grain harvests, or maybe with the counting of the Omer.

I lean toward an association with Shavuot for three reasons. First, John tends to pick out his references to Passover pretty distinctly, and loves his numerology; there are three Passovers in John, and my guess is that there aren’t more. Second, this text comes in chapter 4, and in chapter 5, right after the healing of the paralytic, we get a discourse about the Son doing what the Father does, which leads promptly into the topic of the testimony of the Baptist, and then:

I have greater witness than that of John: for the works which the Father hath given me to finish, the same works that I do, bear witness of me, that the Father hath sent me. And the Father himself, which hath sent me, hath borne witness of me. Ye have neither heard his voice at any time, nor seen his shape. … Search the scriptures; for in them ye think ye have eternal life: and they are they which testify of me. … Do not think that I will accuse you to the Father: there is one that accuseth you, even Moses, in whom ye trust. For had ye believed Moses, ye would have believed me; for he wrote of me. —John 5.36-37, 39, 45-46

This language evokes the appearance on Sinai, which only Moses saw or could bear to see, and the giving of the Torah there.

But the third and last reason is the simplest. How does chapter 4 begin? With passing through Samaria—a territory that, like Moab, was inhabited by relatives of the Jews, but widely hated relatives who were associated with lewd practices and corrupted religion; and while he is there, he speaks to a woman who has no husband, inviting her to be united to the chosen people.

Footnotes

1I’ve written about this once before, back when I was writing via Blogspot.

2The designers of the solar calendar didn’t realize this at the time, as it was not then known that the earth does orbit the sun. However, the tilt of earth’s axis causes not only the seasons (in the temperate zones), but, for the same reason, makes the point on the horizon from which the sun appears to rise to move north and south of due east; for us, sunrise is due east only on the equinoxes.

This rule does not apply in the tropical or polar zones. The only place it absolutely does not apply is the equator itself, which always sees the sun rise due east; but it is irrelevant in practice throughout the tropics, since they lie as close to the equator as makes no difference in climatic terms, and the observable change in the sun’s position throughout the year is negligible in places like Ecuador, Indonesia, Kenya, or Sri Lanka. Conversely, in the polar zones, the sun only rises and sets once per year. Its path through the sky can be seen slowly spiraling further up until what is, in temperate regions, the solstice. After that, it slowly spirals down again, to its single dusk on the other equinox. Hence, for opposite reasons, neither the tropics nor the poles have seasons: they have only the binary contrast of an isochronic day and night—whether both last a dozen hours, or a baker’s dozen fortnights.

3Apologies for any mistakes (especially since I had to math out the dates for a couple of these). I don’t think I included any observances that were not standard in the first century, but I may have missed a few that were already the norm.

4I used to think that whether the Ark of the Covenant was present in the Second Temple was debated, but apparently not. (This does explain why, when Pompey came to Jerusalem and violated Temple protocol by entering the Holy of Holies, nothing happened to him! I mean, he lost a civil war to Cæsar, fifteen years later, but that doesn’t seem related.) According to II Maccabees 2, Jeremiah rescued the Ark from the wreck of Solomon’s Temple and concealed it somewhere on Mount Nebo, just northeast of the Dead Sea (in modern Jordan).

5If my source here is correct, only corn outstrips wheat today; rice is third, with barley coming in fourth.

6Namely, Judah Loew ben Bezalel (c. 1520?-1609), also known as the Maharal. Many famous rabbis are known by a nickname that, in Hebrew, is acronymic: Rabbi Moshe ben Maimon, or Maimonides, an eminent Jewish Scholastic, is often called the Rambam, and Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism, is named the Besht. What words are included in the acronym can seem a little arbitrary: Maharal abbreviates the phrase Morenu ha-Rav Rabi Loew, “Our teacher the Rabbi Loew” (Loew, meaning “lion,” was held to be a German/”secular” equivalent of his Hebrew name Judah).

7That is, in many Judaic traditions. In this respect, Jewish practice tends to differ along lines defined by ethno-regional customs (or at least, customs that were ethno-regional before the Alhambra Decree, but we can’t stop to kvetch about Ferdinand and Isabella now or we’ll be here all night).

8Tisha b’Av (“the Ninth of Av”) is a fast commemorating the destruction of the Temple, and thus did not exist as such in the time of Jesus; I couldn’t find information about when Lamentations was read before then, or indeed whether it had a dedicated holiday. My guess would be that if it did, it would have been on Asarah b’Tevet (see the liturgical calendar above).

9This may strike people who know that Sukkot is a very joyful festival as deeply weird. My suspicion is that the typically pessimistic Christian reading of this book is all out of balance. We associate Ecclesiastes with the dictum “Everything is meaningless” or “Everything is vanity.” The word translated “meaningless” or “vanity” can mean that, and is the same as the root of the name “Abel”: hevel [הֶבֶל], meaning “vapor, breath, steam,” and thus something transitory or ephemeral. I think that’s the key to the book—not that everything is meaningless, but that everything is brief. That can be “vexation of spirit” if we do not learn to accept it (and does long vex “the Preacher” who narrates the book), but doesn’t have to be. Nor is this without reflexes in the New Testament. Consider the lilies of the field, how they grow: they neither toil nor spin; yet I tell you that Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. Now if God so clothes the grass of the field, which today is, and tomorrow is thrown in the oven …

10Obviously Ruth had a mother-in-law in Naomi already, and one to whom she was quite attached; it only just occurred to me that Rahab would also have been her mother-in-law.