“Before I Was So Strangely Interrupted”

Now that the paschal cycle, and even its little train of post-Pentecostal solemnities, has wrapped up, we’re jumping back into Mark. Thanks to how early Easter was, we’re only in chapter three. Considering how long it’s been since I posted anything—and especially, anything up-to-liturgical-date; my last post was the end of a three-parter on Pentecost!—I’m going to try and be a little less elaborate with my next few posts, stick to the highlights. We’ll begin with this past Sunday’s Gospel passage, which was the Second Sunday after Trinity (which, for 2024, equates with the Tenth Sunday in Ordinary Time).

Mark 3.20-35, RSV-CE

And the crowd came together again, so that they could not even eat. And when his friendsa heard it, they went out to seize him, for they said, “He is beside himself.”b And the scribes who came down from Jerusalem said, “He is possessed by Beelzebul,c and by the prince of demons he casts out the demons.” And he called them to him, and said to them in parables, “How can Satan cast out Satan? If a kingdom is divided against itself, that kingdom cannot stand. And if a house is divided against itself, that house will not be able to stand. And if Satan has risen up against himself and is divided, he cannot stand, but is coming to an end. But no one can enter a strong man’s house and plunder his goods, unless he first binds the strong man; then indeed he may plunder his house.

“Truly, I say to you, all sins will be forgiven the sons of men,d and whatever blasphemies they utter; but whoever blasphemes against the Holy Spirit never has forgiveness, but is guilty of an eternal sin”—for they had said, “He has an unclean spirit.”

And his mother and his brethrene came; and standing outside they sent to him and called him. And a crowd was sitting about him; and they said to him, “Your mother and your brethren are outside, asking for you.” And he replied, “Who are my mother and my brethren?” And looking around on those who sat about him,f he said, “Here are my mother and my brethren! Whoever does the will of God is my brother, and sister, and mother.”

Mark 3.20-35, my translation

And they came into a house; and yet again the crowd came together, so that they were not able to eat none of their bread. And when his folksa heard about it, they set out to lay hold of him, for they were saying that “He’s out of his wits.”b And the scholars from Jerusalem, coming down, said that “Beelzebulc has him” and that “By the prince of the demons he casts out demons.”

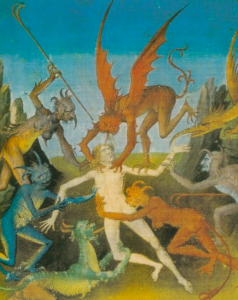

Anonymous painting of a man being attacked by

demons (no date given—15th cent., maybe?).

And, summoning them, he said to them in analogies: “How is Satan able to cast out Satan? And if his kingship is divided, that kingship is not able to stand; and if a household is divided from itself, that household will not be able to stand; and if Satan stands against himself or is divided, he will not be able to stand, but has an end. But no one is able to come into the household of a strong man and plunder his things, unless first he will bind the strong man, and then he will plunder his household. Amen, I tell you that everything will be remitted to the children of men,d the sins and the defamations which they may defame by; but if one should defame the Holy Spirit, he has no remission in the world, but is liable for an eternal sin. (For they were saying: “He has an unclean spirit.”)

And his mother and his brotherse came and, standing outside, sent for him, calling him. And, the crowd being seated around him, these others said to him: “Look, your mother and your brothers are outside looking for you.” And answering them, he said: “Who are my mother or my brothers?” And looking around at those sitting in a circle around him,f he said, “Look, my mother and my brothers: for whoever does the will of God, that person is my brother and sister and mother.”

Textual Notes

I’ve re-paragraphed my translation compared to the RSV, obviously. For theirs or mine, remember: stuff like chapter and verse divisions, paragraph breaks, quotation marks, etc., these are all later impositions meant to help clarify the text. They don’t hold the same authoritative status as the text itself! The RSV’s decision to put the part about “blaspheming the Holy Ghost” in a paragraph unto itself, and moreover to combine what Jesus was saying immediately before that with its preceding context, just strikes me as weird (not that the RSV is the first version of the Bible to make this weird decision). To my mind, everything up until mom and the boys show up says continuity, so I tried to make the paragraph divisions more natural.

a. his friends/his folks: The Greek here, οἱ παρ’ αὐτοῦ [hoi par’ autou], literally means “those from his”; this was an idiom, a little like the fossilized expression “kith and kin” (kith is an otherwise obsolete term from Middle English, meaning “acquaintances, neighbors, familiar people”).

b. He is beside himself/He’s out of his wits: I almost went with the rendering “He’s out of it,” which is what the verb (ἐξέστη [exestē]) almost-literally translates to. But, besides being excessively casual, that expression in English normally means being disoriented from exhaustion, not “having a mental health episode.”

c. He is possessed by Beelzebul/Beelzebul has him: Maybe it’s just because I’m acclimatized to “possess” as a technical term of theology, but personally, I find the more literal “Beelzebul has him” a much more vivid (and frightening!) way of putting it.

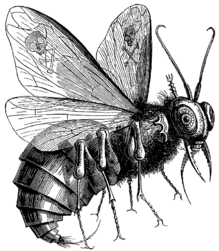

About this Beelzebul, or “Beelzebub” as the Vulgate has it. You may have heard that it means “lord of the flies” (as in the horrifying novel of the same name, where the demon is implied to be present in the rotting head of a pig). It does. The name seems to descend from that of a Philistine deity, and is compounded of Semitic elements. Baȝal [בַּעַל] was a common divine name in ancient Canaan, borne by several gods collectively called “the baals,” and meant simply “lord” (or “husband”); z’vwv [זְבוּב], meanwhile, meant “fly,” as in the insect. (It might have been an onomatopoeia, actually!) Scholars disagree on whether this was the native name for the divinity or not. If it was what the Philistines themselves called this god, the idea was probably that Baal-z’vuv had authority over flies, and could therefore drive them away, along with the sickness and rot they were associated with.

Beelzebub (1863), illustration by Louis le

Breton for the titular demon’s entry in

the Dicitonnaire Infernal of Jacques

Collin de Plancy.

However, the name “Baal-z’vuv” could have been given by the Jews, to imply that this god was a pile of excrement. (In fact, this looks as if it were something of a running joke about the baals.) If so, it was likely a pun on the real name Baal-z’vul [זְבֻ֖ל], probably meaning “lord of the high place” (high places being common sites of sacrifice in ancient Israel, and held by the “Deuteronomistic” school* to be, at least intermittently, a threat to Israelite monotheism.†) This would make both “Beelzebul” and “Beelzebub” likely, defensible readings of the text—the former would record the deity’s original name, and the latter, the standard Jewish expression of derision for that particular idol.

d. sons of men/children of men: In this phrase, I’ve actually indulged in a bit of verbal jugglery that I can only hope isn’t too hypocritical for a guy who’s always banging on about how translations should be and can be way more literal than they are. The RSV’s “sons of men” is, strictly, correct; τοῖς υἱοῖς τῶν ἀνθρώπων [tois huiois tōn anthrōpōn] does mean that. However, ἄνθρωπος [anthrōpos], while grammatically masculine, is more of a generic word for “person” (as the English “man” used to be‡) than a term specifically for male men; the word ἀνήρ [anēr] would normally be used for the sex-specific meaning. Yet the translation “sons of people” sounds so goofy, I couldn’t bring myself to use it. Moreover, the expression “sons of men” is generic anyway—the idea here isn’t to exempt daughters. So basically, I swapped the generic-ness from the second noun to the first, and the gendered-ness from the first to the second, in order to produce an English sentence I could live with.

e. his mother and his brethren/his mother and his brothers: Cue all the stupidest arguments in the world, from both Protestants and Catholics, about what this text “proves” vis-à-vis the immaculacy or sinlessness or perpetual virginity of the Theotokos. I’m going to make a list of things this text doesn’t prove, based on arguments I’ve seen that annoyed me.

The Last Supper, a fresco by Pietro

Lorenzetti for the Lower Basilica of St.

Francis in the city of Assisi (of

uncertain date, possibly ca. 1316-1319).

- No, the fact that Jesus had “brothers” doesn’t prove St. Joseph had children with the Blessed Virgin. I’ve read that Aramaic has no distinct word for “cousin,” and I can’t say I ever learned a word for “cousin” in Greek either (Classical or Koiné); but, without even chasing those to ground, this text wouldn’t prove anything anyway, because the “brothers” could easily be stepbrothers, sons of St. Joseph from a prior marriage (in fact, many Christians think so). And that’s without getting into non-literal uses of the word “brother” that are plenty common in many languages and cultures: not all jocks have either of the same parents, bro.

- Equally, those interpretive possibilities don’t prove that the Theotokos was perpetually virgin. Do I believe that she was? Absolutely. But I believe that on the authority of the Church, not a fallacious appeal to someone else’s argument not being proven.

- In much the same way, this doesn’t prove the Theotokos disbelieved or doubted her Son’s mission at this, or any, time. The fact that someone goes somewhere with a group of people doesn’t prove that they’re all agreed about the purpose of their trip, now does it? If (as the text seems to suggest) this was meant to be a kind of intervention on their part, St. Mary would have had a motive to come even if she didn’t agree with them. It’d be natural for a mother, especially a fiery woman like her, to make a point of showing solidarity with him then.

- And by the same token that this doesn’t prove she sinned, it doesn’t prove her sinless. It proves, in fact, basically nothing!

- It doesn’t even really prove his folks were trying to have an intervention. (That phrase in v. 21, “they were saying,” is as vague in Greek as it is in English: “he’s out of his wits” could have been what Jesus’s brothers were saying, or it could have been what the ever-amorphous “they” were saying.) I do think “intervention attempt” is the most convincing interpretation, and it lines up with passages like John 7 or Mark 6. But it would also be possible to read this as his family trying to scoop him up and just get him somewhere quiet for a while. He’s drawing crowds everywhere he goes, he’s got a segment of the Jerusalem clergy calling him a demoniac—not a safe position to be in! Not only a family who disbelieved in his mission, but one that was unsure, or even one that did believe, would all have had motives to try to protect him. (I mean, look at St. Peter. He’d been in the inner ring of the inner ring of the disciples for a year or more, and he was rebuking Jesus for predicting the Passion, a matter of minutes after Jesus’ identity had been revealed to him by the Father!)

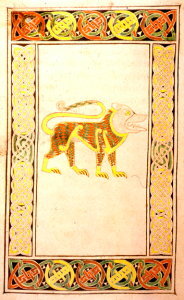

St. Mark’s lion, from the Book of Durrow,

the earliest surviving evangeliary (book

of the Gospels) illuminated in the

Insular style, c. 700.

f. about him/in a circle around him: See though, this is what I mean about the unnecessary un-literalism. It’s right there: κύκλῳ [küklō], “in a circle.” What do we gain by leaving out that charmingly kindergarten image?

The Unpardonable Sin

Ha, if you seriously thought I was going to write about this, … that was actually a pretty reasonable assumption on your part, given what all else I’ve written about. But I’m in fact not going to! It’s out of my depth, and I don’t have the time to deepen before posting this. If I’m very lucky, I might conceivably finish the post for this coming Sunday’s Gospel before this coming Sunday—say a prayer for me, if you would.

Footnotes

*The history contained in Joshua, Judges, Samuel, and Kings** is attributed by most modern scholars to a Judaic theological “school” known as the Deuteronomist, often associated with the high priest Hilkiah. He served under King Josiah (r. ca. 640-609 BC), and reportedly found a copy of the Torah (or of a part of it) in the First Temple. The conventional interpretation of this event, according to the Documentary Hypothesis—a nineteenth-century theory about the composition of the Hebrew Bible—is that what Hilkiah found, or rather, “found,” was the Book of Deuteronomy. Most scholars now dismiss the Documentary Hypothesis, or subscribe only to a heavily modified version of it; however, elements of it are widely considered valid, including the idea that Deuteronomy is a separate composition appended to the Torah later.

**Samuel and Kings are not divided in the Hebrew Bible; the custom of splitting them into I and II halves comes from the Septuagint. The same is true of the books of Chronicles and Ezra (though most Bibles use the names Ezra and Nehemiah rather than I and II Ezra, likely for … reasons).

†Or, possibly, monolatry. The older parts of the Tanakh seem consistent with the idea that other gods are real (or were at least believed, even by faithful and non-idolatrous Israelites, to be real), but that Israel was commanded to reserve its worship exclusively for the God of their father Abraham (hence the term: Gr. μόνος [monos] “only, alone” + λατρεία [latreia] “service, devotion, worship”). Sometimes this practice is also called henotheism (Gr. ἕν [hen], “one”); however, some scholars use that term specifically for the syncretic idea that all the “popular” gods are aspects of a single supreme deity, exemplified in late classical Græco-Roman paganism and certain forms of Hinduism. Monotheism proper—the denial that other gods even exist, or at any rate that they are “gods” in anything like the same sense as the God—appears mainly in material considered relatively late, and of course in the New Testament.

‡If you’re wondering why a hidebound reactionary such as myself isn’t protesting against this change in the meanings of words, it’s because I think this happens to be a good change. To quote my master C. S. Lewis’s neglected masterwork, Studies in Words (p.6), “Language is an instrument for communication. The language which can with the greatest ease make the finest and most numerous distinctions of meaning is the best.” Since borrowing the term human from French a few centuries ago, it has become—pace Professor Tolkien (and that is hard for me to write!)—the best term for our species. This is because having human for our species, and allowing man to become as gender-specific as woman, means that we can make finer, more numerous distinctions with English than we could when man was doing double duty. (We must of course be careful not to project historically irrelevant readings back onto older texts, but we have to do that with a lot of other words anyway.) Was the shift in the meaning of the term man effected by feminist political advocacy rather than philological principle? I don’t know; probably. Oh no?