Well, I’m really Catholic now. Yesterday, on the feast of Pentecost, I participated in my first infant baptism. Coming as I do from an Anabaptist background, this is kind of a big deal. This event was made particularly meaningful for me not only because the baptizand bears the name of my patroness, Hildegard, but even more so because she is the daughter of my professor, Dr. Kimberly Belcher (who has made a previous appearance here), who was instrumental in helping me work through my own evolving beliefs on baptism.

Ironically, as I think about it, other Mennonites had as much of a role to play in this evolution of mine. I had first of all undergone a significant shift toward sacramentality, particularly in relation to the Eucharist, while volunteering with Mennonite Central Committee in Haiti and becoming involved with a Catholic parish there. But my first noticeable shift in thinking with regard to baptism came from a 2008 article published in the magazine The Mennonite, titled “Mennonite but Not Anabaptist,” in which Mennonite pastor Chad Mason argued against rebaptizing Christians who had been baptized as infants, on the basis that the 16th-century Anabaptists’ driving reason for opposing (indiscriminate) infant baptism – namely, its representing more an induction into civil society than formation within a community of disciples – no longer exists. Those who perceive Anabaptism as being fundamentally individualistic from the beginning are profoundly mistaken, but it is a rather understandable mistake given the way that Mennonites have come to rationalize their continued rejection of infant baptism, now that it no longer represents what Mason referred to as an “entanglement with the machinations of state power.” Based on the concern that in today’s context “rebaptism may serve to underwrite individualism,” he concluded his article in this way:

Our capitulation to the autonomy of the individual, manifested in our ongoing willingness to rebaptize upon request, is not only a kind of predation on other communions; it is a kind of cannibalism of our own. By handing baptism over to the choice of the individual, we are eating ourselves alive.

After all, if we accept a wayward Catholic’s rejection of her baptism on the grounds that she did not choose it and can’t remember it, what answer can we muster for the departing Mennonite who rejects our faith on the grounds that he was merely born and raised Mennonite?

The world is not medieval anymore. All Christian communions have now been removed from power by Western liberalism. Thus have we come, ironically, to a historical moment when Mennonites may need to reject Anabaptism in order to preserve the Mennonite association of baptism with discipleship and the Mennonite disassociation of baptism from power. Especially in places like southeastern Iowa, it has become fair to ask which community is closer to being in power, Mennonites or Catholics. The answer, of course, is neither. Both now stand in solidarity as varied expressions of God’s alternative society, distinct from the dominant power of American individualism.

In order to be radical in their proclamation to such power, Mennonites should refuse rebaptism to every person who wishes to act as his own pope. Perhaps then we may all, together, eat the flesh and blood of Jesus instead of our own.

Mason’s call to end the “cannibalism” of rebaptism was not well received by its readership, but between his appeal to a deeply Mennonite sense of Christian community as counter-culture and my recently developed sympathies toward a Catholic sense of sacramentality, I was convinced by his argument. And coming to disagree with the practice of rebaptism meant that, by extension, I had to acknowledge infant baptism as valid, even if I retained a preference for adult baptism as a more normative form of initiation into the community of faith.

That’s pretty much where my thinking was when I came to Kim’s course on the sacraments at the beginning of my graduate studies in theology (by which point I had decided to be confirmed in the Catholic Church). As I would soon learn, Kim has a gift for pushing her students to think beyond what they have articulated. And I did a lot of thinking. I convened a biecclesial council in my head. I wrote papers to find out what I believed, eventually – to make a long story short – coming out in favor of dual normativity (i.e., that infant and adult baptism should be considered not only equally valid but equally normative, as applicable to complementary pastoral situations).

One piece of the intensive (internal and external) discussion that brought me to that conclusion was Kim’s own work on the dynamic agency of infants (discussed at length in her book adapted from her doctoral dissertation), which forced me to question some of my inherited assumptions about individualism and passivity in infant baptism. Her analysis of the dynamism of infancy came back to haunt me even while watching a child dedication in a Mennonite church: noticing the babies’ movements, their gazes, their activeness, there was no doubt that they knew something significant was going on.

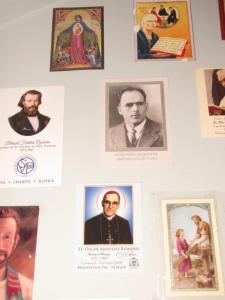

And so did Hildegard – even though it will be many years until she can articulate it with her mother’s astuteness. May the faith into which she has been baptized, surrounded by the love of her family and friends and the prayers of the saints, continue to nourish and form her in the love of God and neighbor throughout her life.