This is my second post on the encyclical Populorum Progressio by Paul VI; you can read the first part here. For this discussion we read the middle third, paragraphs 32-60. The material in this section splits into two parts. Paragraphs 32-42 continue the discussion of integral or balanced development; important items discussed include the goals of development; he role of education in shaping a Christian humanism as part of development; and the roles of families, professional organizations, labor unions, and cultural groups in development. The second part, paragraphs 43-60, discusses more the moral underpinnings of development and some consequences of these, especially for richer nations.

As happens often, our discussion jumped to this second part and a discussion of the role of nation states in the process of development. This section begins by outlining the three duties that the common good imposes on wealthy nations with regards to development:

Their obligations stem from the human and supernatural brotherhood of man, and present a three- fold obligation: 1) mutual solidarity—the aid that the richer nations must give to developing nations; 2) social justice—the rectification of trade relations between strong and weak nations; 3) universal charity—the effort to build a more humane world community, where all can give and receive, and where the progress of some is not bought at the expense of others. (par. 44)

The first duty, of solidarity, is clear, and reflects a growing concern in CST that our duties to our brothers and sisters must transcend national boundaries. The second two, social justice and universal charity, highlight ideals raised by Pius XI in Quadragesimo Anno: the duty “restore society according to the mind of the Church on the firmly established basis of social justice and social charity.” (QA, par. 126). We had a detailed discussion of these earlier: see QA IV.

The difference, however, is that here it is nations, and not individuals, who are called to act in these ways. Many of us read the text as advocating that nations are bound by the same moral standards that bind individuals–an interesting proposition since this raises some uncomfortable questions. Nations traditionally been allowed to employ violence (war, police authority, the death penalty) in ways that individuals are not. If nations are to be held to the same standard as individuals, does this mean that these are not to be allowed either? Certainly, John XXIII began to call into question the traditional interpretation of just war theory, which Vatican II and Paul VI continue. And more recently, the last three popes has challenged the licity of the death penalty, ending with Pope Francis declaring it inadmissible. It is not clear how far to push this, but it is a challenge to some of our comfortable shibboleths.

Our discussion turned on a different facet: if nations are a fundamental social structure, how do we get nations to behave and adhere to these moral obligations? Returning to a previous point, do we need a transnational authority with the power to force states to behave? Both the Council Fathers and John XXIII did explicitly call for such a political authority, as can be seen from our previous discussions. Paul VI does not, though he also criticizes an unwarranted attachment to the nation-state:

There are other obstacles to creation of a more just social order and to the development of world solidarity: nationalism and racism….Haughty pride in one’s own nation disunites nations and poses obstacles to their true welfare. It is especially harmful where the weak state of the economy calls for a pooling of information, efforts and financial resources to implement programs of development and to increase commercial and cultural interchange. (par. 62)

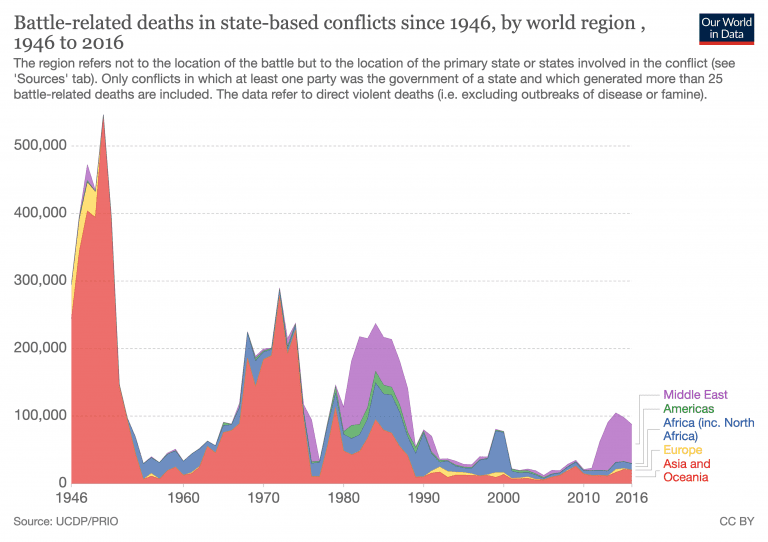

I am not sure how to get nations to act rightly, but in my mind how do we get individuals to act rightly? By persuasion and good example, and by non-violent intervention–think, for instance, of the ways that by-standers can intervene to diffuse bad situations, or the ways we can respond when we see domestic violence. And only as a last resort do we resort to police authority or indeed the personal application of violence. Similarly, nations should act in the ways they want other nations to act, both because it is the right thing to do, and because it establishes a moral standard that others can see and compare bad actors to. Nations that have histories of political violence or repression of minorities are sensitive to their reputations–you can see this in the ways they gleefully respond when the US is caught out not living up to its own ideals.

The role of military force, as a last resort, is still unclear in my thinking, though I definitely think that active non-violent engagement is the necessary. This is hard, and expensive, but as one of our group pointed out, Paul VI explicitly calls for redirecting resources from the military to human development:

We asked world leaders to set aside part of their military expenditures for a world fund to relieve the needs of impoverished peoples. What is true for the immediate war against poverty is also true for the work of national development. Only a concerted effort on the part of all nations, embodied in and carried out by this world fund, will stop these senseless rivalries and promote fruitful, friendly dialogue between nations. (par. 51)

Note the connection the text draws between making these changes and promoting the kinds of engagement between nations (e.g., dialog) that will lead to nations upholding their ethical obligations.

Another member of our group wanted to draw parallels between the discussion about families (paragraph 36) and the behavior needed between families of nations. Like life in our families, this is complicated (sometimes messy) and not reducible to simple prescriptive rules. Nations have duties to their citizens, as well as to the worldwide community, and the question is how to balance these? A good recent example of this is the problem of distributing the Covid-19 vaccine: nations must protect their citizens, but we have a duty to provide the vaccine for everyone. Contrast this vaccine distribution plan from World Health Organization with what is actually happening.

One member of our group noted that this is good in theory, but it depends on people having a broader sense of identity, but most of us have been raised since childhood to think of the pinnacle of their social identity as their national identity. In other words, we are not acculturated to see ourselves as “world citizens”, and if the people do not feel this way, can we reasonably expect their governments to act this way? To me, this leads to an important question: how has Catholicism failed to balance the development of a national identity and a “love of county” with an appreciation of ourselves as “pilgrims and strangers on earth” (Hebrews 11:13, KJV) with no true home but heaven? In the American context, this was driven by the bitter anti-Catholicism of the 19th century, which denied that someone could be both a Catholic and American citizen. This led to a concerted effort by the American Church to prove that Catholics could be and were “the best of Americans.” I first read this expression in a discussion of the history of the Knights of Columbus, who have what I regard as somewhat unhealthy emphasis on patriotism as a virtue. (For the record, this is the reason I have not become a Fourth Degree Knight.) But I think it applies more generally to the American Church, particularly in years before Vatican II: they were so focused on being accepted by the broader nation that they lost sight, to a degree, that they were called to be members of something larger than themselves. The problem now is to reverse this, and get American Catholics to see themselves as brothers and sisters to the whole world–not in a facile, “Kumbaya singing” sort of way, but in way that really affects them and causes them to unite themselves with others beyond their borders. As I write this I am reminded of a quote from Dostoevsky that was beloved by Dorothy Day, “Love in reality is a harsh and dreadful thing, compared to love in dreams.” This is the kind of love we need to hold for the whole world.

This led to a fascinating but somewhat tangential discussion about different kinds of nationalism. One member of our group brought up the work of Henri Bergson, a French philosopher. In his book Two Sources of Morality and Religion, he distinguishes between “open” and “closed” morality, which in turn leads to an open and closed nationalism. A closed nationalism is inward looking, and concerned with the preservation of a particular society–so much so that it excludes and subordinates other societies. An open nationalism, on the other hand, welcomes and accepts the existence of other societies, and wants to make connections with them. I think that one way to illustrate this distinction, though not perfectly, is to look to the Brexit debate in Great Britain, which polarized between the “Leavers”, who valued British identity and sovereignty that they were willing to break off from the European Union to preserve their vision of society, and the “Remainers”, who saw that Britain was a better society for being part of a transnational organization like the EU. It would seem that the Church, to balance this tension, needs to inculcate an open nationalism, one which allows people to love their own nation, society and culture, but not in a way that prevents them from being open to the world around them.

Paul VI addresses this dichotomy in the context of development. He laments the fact that development leads to a conflict:

either to preserve traditional beliefs and structures and reject social progress; or to embrace foreign technology and foreign culture, and reject ancestral traditions with their wealth of humanism. (par. 10b)

He then warns development experts to not be possessed by a closed nationalism that leads to this conflict:

The culture which shaped their living habits does contain certain universal human elements; but it cannot be regarded as the only culture, nor can it regard other cultures with haughty disdain. (par. 72a)

In the final part of our discussion we focused on paragraph 37 on population growth. Both John XXIII and the Council Fathers addressed this question, but for some reason we skipped over these passages in previous readings. In full disclosure: in the past I have blogged extensively about population growth: you can see two posts from 10 years ago here and here. I wanted to challenge what I felt was a certain complacency about over-population among some Catholics, which includes some who seem to feel that over-population can never be regarded as a problem, no matter what the circumstances. Some of the papal documents we read edge in this direction, as have more recent documents (e.g., Laudato Si, which I felt could have used more nuance on this question).

However, Paul VI seems to have recognized the problem, writing

There is no denying that the accelerated rate of population growth brings many added difficulties to the problems of development where the size of the population grows more rapidly than the quantity of available resources to such a degree that things seem to have reached an impasse. (par. 37a)

He stresses the importance of conscience in this matter, and calls upon Catholics to “to take a thorough look at the matter and decide upon the number of their children.” (par. 37c) This was, at the time, an important point, since it made it clear that Catholics could (and perhaps even should) consider limiting the size of their families in light of the broader context–e.g., the improvement in public health which led to substantial decreases in maternal and infant mortality. Later, in Humanae Vitae, he will (controversially) address the question of means, but here he is has raised an important point about goals.

This led to a digression about population growth and the broader context: what factors should influence a family’s decisions about how many children to have? This is a complicated problem, since it involves both population and consumption: you can support more people if each person consumes less. The problem in the world today is that there are the relative few who consume much more than the masses of humanity. Solidarity calls for either significantly reducing the consumption of the minority, or raising the living standards of the majority, causing them to consume more–both solutions present serious obstacles. I refer the interested reader to my blog posts above. (Note that one is labeled “part I”, but in fact I never got around to writing “part II”.)

I want to conclude this with a passage buried deep in this section which I think gets to the heart of this encyclical, and the moral imperative that Paul VI was articulating. It remains as true today as it was over 50 years ago:

Countless millions are starving, countless families are destitute, countless men are steeped in ignorance; countless people need schools, hospitals, and homes worthy of the name. In such circumstances, we cannot tolerate public and private expenditures of a wasteful nature; we cannot but condemn lavish displays of wealth by nations or individuals; we cannot approve a debilitating arms race. It is Our solemn duty to speak out against them. If only world leaders would listen to Us, before it is too late! (par. 53)

If only each of us would listen before it is too late!

Cover Image: Pope Paul VI by BastienM, used with permission, from Wikimedia Commons.