I’ve been struggling a lot lately. For months I’ve been in a state of perpetual outrage over Donald Trump and his cruelty, the hatred and ignorance of his supporters, the cowardice of the Republican Party, and the majority of white Americans – including most Christians – who apparently still support this man and his policies. I say struggling because I have recently become aware of my disappointment and outrage evolving into hatred, which has in turn released something violent and destructive within me. I’ve been walking around with a knot in my stomach. I’ve been deeply anxious and hair-trigger touchy. I’ve caught myself daydreaming about Trump’s death or incapacity. I’ve even indulged fantasies about a cleansing civil war, with all the attendant homicidal ideation that implies.

None of this surprises me, mind you. I’ve long been aware of the fact that my capacity for hatred and violence is very deep, especially as a response to what I perceive as injustice. You might disagree, but I think we all possess this dark reservoir within us: “The human heart is the most deceitful of all things, and desperately wicked,” says Jeremiah, a diagnosis endorsed by Jesus, who said, “From within people, from their hearts, come evil thoughts, unchastity, theft, murder, adultery, greed, malice, deceit, licentiousness, envy, blasphemy, arrogance, and folly. All these evils come from within and they defile.” (Matthew 7:21-23)

Recognizing that I come by this propensity for evil naturally is no excuse for indulging it. My mother used to say that the key to success in life is learning to take a stand against oneself, and I’ve found that to be true throughout my adult life. For me, that usually involves choosing a different model than the one I’m sinfully obsessing about at the moment. Lately, I’ve been obsessing about Donald Trump, who in the perverse chemistry of human psychology (see Girard, Rene) has become something of a model for me. I’ve been mirroring his hate and his violence and feeding it back to him. If I’m going to break this cycle and return to spiritual and psychological health, I need a different model. Gratefully, I have one at hand, and so do you.

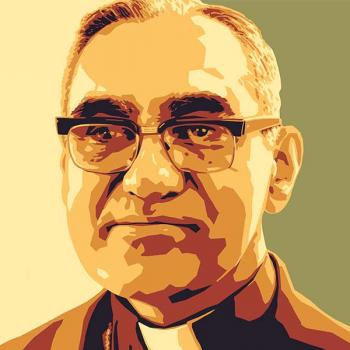

This man was insulted and demeaned all his life. He was threatened with death hundreds of times. He was beaten with fists and pelted with stones. He had friends murdered, often precisely because of their association with him. He was oppressed by the full weight of the modern state: thrown in jail, made a special target by the FBI, repeatedly and unjustly charged with crimes, his privacy sundered, lies about him planted in the press, some of his confidants blackmailed into becoming informers. A cross was burned on the front lawn of his home while his small children slept just yards away. One time, someone fired shotgun blasts into his front door. Another time, his home was firebombed. Later, someone left twelve sticks of dynamite on his front porch, but they failed to explode. Finally, at the age of 39, he was shot in the face and died.

Yet this man, who endured so much hatred and violence, remained committed to nonviolence until his last breath, not as a tactic but as an imperative of his Christian faith. He had enemies, millions of them, but each one of them chose him. He chose to make no man his enemy. Thus, he could write:

“Nonviolence means avoiding not only external physical violence but also internal violence of spirit. You not only refuse to shoot a man, but you refuse to hate him.”

“Returning hate for hate multiplies hate, adding deeper darkness to a night already devoid of stars. Darkness cannot drive out darkness; only light can do that. Hate cannot drive out hate; only love can do that. Hate multiplies hate, violence multiplies violence, and toughness multiplies toughness in a descending spiral of destruction.”

“By opening our lives to God in Christ, we become new creatures. This experience, which Jesus spoke of as the new birth, is essential if we are to be transformed nonconformists … Only through an inner spiritual transformation do we gain the strength to fight vigorously the evils of the world in a humble and loving spirit.”

“Now there is a final reason I think that Jesus says, ‘Love your enemies.’ It is this: that love has within it a redemptive power. And there is a power there that eventually transforms individuals. Just keep being friendly to that person. Just keep loving them, and they can’t stand it too long. Oh, they react in many ways in the beginning. They react with guilt feelings, and sometimes they’ll hate you a little more at that transition period, but just keep loving them. And by the power of your love they will break down under the load. That’s love, you see. It is redemptive, and this is why Jesus says love. There’s something about love that builds up and is creative. There is something about hate that tears down and is destructive. So love your enemies.”

Martin Luther King, Jr., knew for a long time that his enemies would kill him eventually. In 1963, after the death of John F. Kennedy, King told his wife, Coretta, “This is what is going to happen to me also. I keep telling you, this is a sick society.” The night before his assassination, he told a crowd in Memphis, “Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will.” Yes, King knew he would become a victim of lethal violence, yet he persisted in love, in nonviolence, in refusing to hate. He chose no enemies. His passion for justice never abated. In fact, toward the end of his life the scope of his vision grew to encompass all the victims of discrimination, war, and economic exploitation, both here and abroad. He worked tirelessly to make the Beloved Community a global reality. But he gave no sanction to hatred in his own heart, fearing that to do so would not only blunt the cause of justice, but would cost him his own soul.

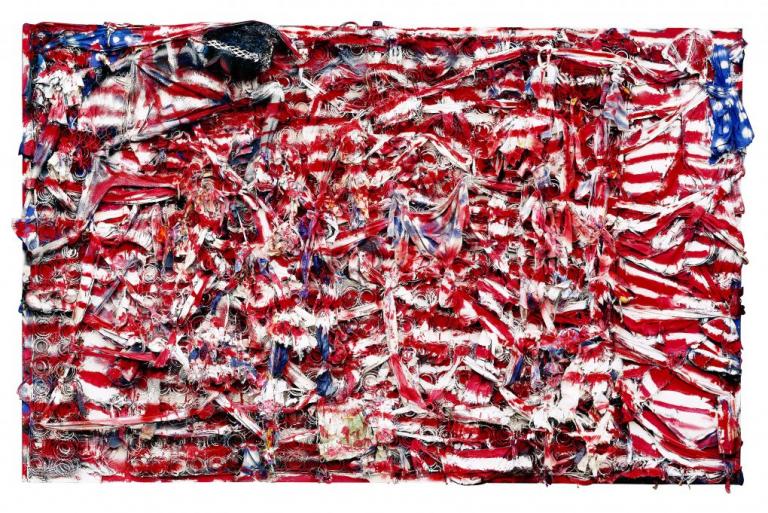

Look, we are facing terrible times. There are reasons to believe that as difficult as things are now, we may look back on these days as the quiet period before the deluge. Despite the comforting lies we tell ourselves, the United States doesn’t hold an exemption from history or human nature. As Eddie Glaudehas said, Americans are only exceptional for our ability to make up fairy tales about our history and ourselves. For 400 years we have sown the wind. Can we fail to reap the whirlwind? All that has come before will come again because the racism and violence at the heart of our national soul have never been expunged. In a sense, Donald Trump has done us a service by ripping off the scab and showing us that the American soul still rots beneath. He himself is a kind of mirror held up to white America, and in that reflected darkness we see all the work that must still be done.

Someone recently declared that we are in a “cold civil war.” I think that’s right, but I also think it’s getting warmer all the time and may well blossom into white-hot flame before long. When it does, Christians will have to remember who we are and who we serve. Dorothy Day said that “I only love God as much as I love the person I love the least.” Who do you love the least? For me, there is no question. It is Donald Trump, the most unlovable figure I can imagine. But Jesus loves him, and Jesus calls us to “love your enemies.” When I wonder how that is possible, Dr. King is there to remind us. In his sermon titled “Our God is Able,” King said:

If at times we begin to despair because of the relatively slow progress being made … let us gain consolation from the fact that God is able, and in our sometimes difficult and lonesome walk up freedom’s road, we do not walk alone, but God walks with us. He has placed in the very structure of this universe certain absolute moral laws. No matter how much we try, we cannot defy or break them; if we disobey them, they end up breaking us. The force of evil may temporarily conquer truth, but truth has a way of ultimately conquering its conqueror. Our God is able. James Russell Lowell was right:

Truth forever on the scaffold

Wrong forever on the throne

Yet that scaffold sways the future,

And behind the dim unknown,

Stands God within the shadow

Keeping watch above His own.

Click here to review Dr. King’s Six Principles of Nonviolence