In a historic moment yesterday, Scotland narrowly voted against full independence and to stick with ye olde United Kingdom. The Union Jack, one of the coolest flags ever, will stay cool. Hadrian’s Wall will not be rebuilt.

In a historic moment yesterday, Scotland narrowly voted against full independence and to stick with ye olde United Kingdom. The Union Jack, one of the coolest flags ever, will stay cool. Hadrian’s Wall will not be rebuilt.

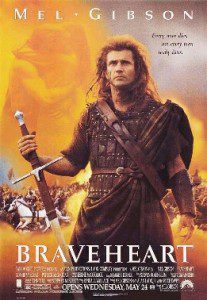

Since I live in Colorado Springs, I didn’t exactly have a dog in the fight, Scotty or otherwise. Still, I was happy to see Scotland vote the way it did—in spite of the fact that those in favor of independence used one of my favorite movies as propaganda: Braveheart.

“This image of Braveheart became so embedded during this period of devolution,” Sally Morgan, a professor of Fine arts at New Zealand’s Massey University, told Australian National Radio a couple of days before the vote. “I think Scotland was kind of ready for this image of itself as this wild, empire defying, Celtic tribesman that needed to be apart from England.”

Mel Gibson’s Braveheart, released in 1995 and winner of five Academy Awards (including Best Picture), has been critical in the campaign for Scottish independence, its images used in posters and its story alluded to by leaders. And really, who could blame ‘em? England’s King Edward “Longshanks” is a big ol’ jerk in the film: He never offered sweet speeches about this “family of nations”—just a lot of cavalry charges and arrow showers. I think even the Queen of England would root for William Wallace and his blue-faced compatriots.

But for me, the film has always been more about faith than anything—faith in something both beautiful and improbable, and a freedom that, for me, transcends who you send your taxes to.

A quick recap of the film: England’s Edward Longshanks rules over Scotland with the proverbial iron fist. The Scots are seriously bummed over England’s rule, and the country offers the occasional half-hearted resistance. But rebellion really doesn’t start crackling until William Wallace (Gibson), ticked over the tragic death of his secret wife, takes the field. The Wallace-led Scots experience success against their nasty Anglo-overlords. Robert the Bruce (Angus Macfadyen), the handsome but calculating noble who many Scots believe should be the land’s rightful king, is even on board.

But not everyone is so sure of Wallace’s long-term success. We’re talking England, after all—a wealthy medieval superpower not to be trifled with. Scotland’s most powerful families begin to hedge their bets. And Robert’s father, a pragmatic politician, cares not a whit about Scottish freedom, but rather for the wealth and prestige of his own family.

It all comes to a head at Falkirk. The Scottish nobility withdraws from the battlefield. A furious Wallace, knowing the battle is lost, charges after a mysterious English knight, yanks off his helmet and discovers … Robert the Bruce. Wallace has been betrayed.

Robert feels horrible about the whole episode. He storms back to his father, overwhelmed with grief and guilt.

“Men fight for me because if they do not, I throw them off my land and I starve their wives and their children,” he bellows. “Those men who bled the ground red at Falkirk, they fought for William Wallace, and he fights for something that I never had. And I took it from him when I betrayed him. I saw it in his face on the battlefield and it’s tearing me apart!”

“Men fight for me because if they do not, I throw them off my land and I starve their wives and their children,” he bellows. “Those men who bled the ground red at Falkirk, they fought for William Wallace, and he fights for something that I never had. And I took it from him when I betrayed him. I saw it in his face on the battlefield and it’s tearing me apart!”

“All men betray,” his father says. “All lose heart.”

“I don’t want to lose heart! I want to believe!”

For me, that was the most powerful moment in the movie. I want to believe.

Wallace and Robert, they wanted to believe in a free Scotland—a pipe dream that nevertheless came true years later, under Robert’s leadership, in Bannockburn. But for me, it spoke to a yearning in my heart—to believe in a just and loving God, to believe in a life created with purpose, not chance, to believe in a purpose and soul and things that science can’t understand, but are nevertheless as real as the screen in front of you.

I want to believe.

Truth is, faith doesn’t come easy for me. What I think and feel is predicated on what I can see and hear and touch. When I place “faith” in something, it’s grounded in some semblance of rationality—placing trust in those who know better than I do about such things. I don’t intrinsically know when a storm might sweep in, so I trust the local meteorologist. I haven’t studied the science behind climate change, but I trust the learned scientists who say the climate is changing.

But while 97% of scientists agree that climate change is a thing, there is no such learned consensus on God. There are a great many intelligent believers just as there are unbelievers. There are scads of reasons to believe. But there are also reasons to not.

And while my personal faith is grounded in the evidence I see for God—historic and scientific, empirical and anecdotal—none of that evidence adds up to conclusive proof. And so I wind up where Robert the Bruce does. I want to believe. I want to have faith. I want to plant my banner in the field of spirit and pay homage to a transcendent truth, an indescribable beauty. I want to believe that we were not meant for this world. I want to believe that we were designed to be better than we are. I want to believe that right and wrong extend beyond human device, that there is a God who loves us.

And while my personal faith is grounded in the evidence I see for God—historic and scientific, empirical and anecdotal—none of that evidence adds up to conclusive proof. And so I wind up where Robert the Bruce does. I want to believe. I want to have faith. I want to plant my banner in the field of spirit and pay homage to a transcendent truth, an indescribable beauty. I want to believe that we were not meant for this world. I want to believe that we were designed to be better than we are. I want to believe that right and wrong extend beyond human device, that there is a God who loves us.

I could be wrong. My faith could be misplaced. I could be, as the Apostle Paul says, a person most to be pitied. It could be that the universe is a cold and empty place and we just cosmic accidents. Perhaps there’s reason to lose heart. Perhaps no one cares if we betray one another.

But that’s not a world I want to live in. I want to believe in something better. And so I do.