Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, directed by Frank Capra, premiered 75 years ago today in Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. The screening was sponsored by the National Press Club, which in itself is kind of interesting, since Mr. Smith spends a portion of the movie punching journalists in the face.

Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, directed by Frank Capra, premiered 75 years ago today in Constitution Hall in Washington, D.C. The screening was sponsored by the National Press Club, which in itself is kind of interesting, since Mr. Smith spends a portion of the movie punching journalists in the face.

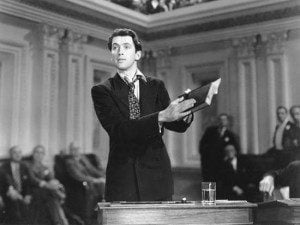

Mr. Jefferson Smith (played by Jimmy Stewart, classic Hollywood’s favorite everyman) is small-town hero in flyover country, selected to fill a vacated senate seat for a couple of months before elections. The corrupt political machine that puts him there figures the naïve Scoutmaster will be too thrilled with the gig to cause too much trouble. But when Smith introduces a bill to build a boy’s camp where powerful boss Jim Taylor has plans for a dam, the scene is set for a showdown: Average Joe against the mightiest powers in the land.

It’s a classic, of course. And yeah, it’s pretty great. While rumor has it that senators walked out of that first screening, it’s reassuring today that politicians—even on the eve of World War II—were always a little suspect.

But something else caught my eye: How much the story mirrors, in a very American way, Jesus’ own trip to Jerusalem. Or it would have, had Jesus been just a well-meaning mortal rube from Nazareth.

When Stewart’s Mr. Smith arrives in Washington, he’s greeted warmly, but with an air of curiosity, too. Smith’s a nice guy, after all, and D.C. denizens know their city is not a place for nice guys. But some, perhaps, believe this unassuming everyman might be something of a savior. Maybe much like some who were waving those palm fronds a couple thousand years ago.

It’s not long before Smith sees the true face of D.C. He’s mocked by Washington’s hard-drinking press corps and—as mentioned earlier—punches quite a few of them. He gets educated quickly to Washington’s less-than-pure operation. It reminds me a little of Jesus walking into the temple and finding it a “den of thieves.”

But it’s only when Smith decides to do something about it that he runs into real trouble. After he proposes his bill, the Taylor political machine—including Smith’s mentor, Sen. Joseph Paine—decides to take the guy down. And even though Payne is reluctant to take part, telling Taylor he has no desire to “crucify” the man, he does. He frames Smith to make it look like his boy’s camp was merely a greedy, profit-taking venture and starts the ball rolling to get Smith expelled. It’s as thorough a betrayal as if Paine was Judas, kissing Jesus on the cheek for 30 pieces of silver.

The betrayal sends Smith to a veritable Garden of Gethsemane—but for Smith in his American tale, his garden is the Lincoln Memorial, and instead of talking with God, he kneels before Lincoln. But then he gets a little pep talk from his assistant, Clarissa Saunders.

She tells him that he’s not the only one who’s battled corruption and political machines. Every political hero fought the same foolish battle, because they had faith in something higher, something better. “All the good that ever came into this world came from faith like that,” she says. And together, they hatch a small plan to be launched during Smith’s Senate-centered crucifixion.

Smith doesn’t do his work on a cross, of course, but rather in a dramatic filibuster. He speaks for more than 23 hours (according to the movie; the filibuster scene itself lasts only for about 15 minutes or so), quoting the Bible and the Constitution, pleading for a little more honesty and decency. He may be thrown out from the Senate on his ear, he says, but at least the people in his hometown will hear that he tried to make Washington a more honest place.

But Taylor’s political machine, which owns a slew of newspapers, undermines even that plan. And in the climactic moments of the movie, Joseph Paine brings in thousands upon thousands of telegrams from his hometown—all from people who believe he’s a liar and a crook. It reminds me of the crowd gathered below Pontius Pilate, screaming for Jesus to be crucified.

In his last scene, Smith quotes Scripture. He scolds his betrayer even as he confesses how much he loved him. And he collapses. The crucifixion is done.

Now, I’m not saying that Capra was creating a biblical allegory. Rather, he was using echoes of Jesus’ passion—one more familiar, perhaps, back then than they are today—to stress Smith’s role as a Washington savior, doing a sacred bit of work.

Those biblical echoes still resonate today, at least for me. And as we head into elections not too many days away, it makes me long for a Mr. Smith or two.