The Capitol of Panem may look all sleek and modern. But when you really examine the place, it looks an awful lot like ancient Rome.

The Capitol of Panem may look all sleek and modern. But when you really examine the place, it looks an awful lot like ancient Rome.

Maybe you knew that already. It’s not any great secret. Suzanne Collins has said that she had Rome in mind when she wrote The Hunger Games, and the whole series is littered with names that come from Roman history and mythology (including Cinna, Portia, Castor, Pollux, Flavia, etc., etc.). Panem’s economy resembles that of Rome, what with all the empire’s sprawling goods carried back to the pampered Capitol. Even the very name “Panem” comes from the Latin phrase “Panem et Circenses,” (“bread and circuses”), first used by the Roman poet Juvenal as a snarky dismissal of how the Roman government distracted the masses.

No mystery as to what those “circuses” were, either: The Colosseum was just about 20 years old when Juvenal first coined the phrase, but it was already the site of many a bloody gladiatorial contest … bearing more than just an accidental resemblance to the Hunger Games.

‘Course, there was something else big happening in the Roman Empire at the time of Juvenal: A fledgling religion called Christianity was beginning to come into its own. The Hunger Games books and movies, including Mockingjay – Part 1, contains hints of that story, too.

Now, I have no idea whether Collins intended to allude to religion, and The Hunger Games series is in no way a tit-for-tat allegory. In fact, trying to draw too much from the movies can be downright frustrating. But what we do see here is pretty interesting.

Take, for instance, Katniss Everdeen—our series’ clear heroine (played by Jennifer Lawrence). If ever there was a Christ figure in The Hunger Games, she’d be it, right? Look at the poster, for goodness’ sake—meshing Katniss and mockingjay together in an almost angelic-like pose that’s also suggestive of a fiery crucifixion. Her story begins with an act of sacrifice—her choosing to volunteer for the Games and taking her sister Primrose’s place. She is like a sacrificial lamb—and indeed, the Capitol sees her and the other tributes as such. The Hunger Games, after all, are built on the idea that the districts need to pay for their earlier sins of rebellion. As a tribute from District 12 (a far-flung province not unlike Palestine in ancient Rome), not much is expected of her.

Take, for instance, Katniss Everdeen—our series’ clear heroine (played by Jennifer Lawrence). If ever there was a Christ figure in The Hunger Games, she’d be it, right? Look at the poster, for goodness’ sake—meshing Katniss and mockingjay together in an almost angelic-like pose that’s also suggestive of a fiery crucifixion. Her story begins with an act of sacrifice—her choosing to volunteer for the Games and taking her sister Primrose’s place. She is like a sacrificial lamb—and indeed, the Capitol sees her and the other tributes as such. The Hunger Games, after all, are built on the idea that the districts need to pay for their earlier sins of rebellion. As a tribute from District 12 (a far-flung province not unlike Palestine in ancient Rome), not much is expected of her.

But as the Games go on, something mysterious and rather marvelous happens: She becomes a symbol of hope—a savior. She wins people over with her honesty and passion. She’s somehow able to wriggle free from every trap her adversaries set for her. The people of Panem begin to see her as a Messiah, in a way—the one who might rescue them from bondage. They dare hope that she’s Panem’s version of the Christ—a word meaning the anointed one.

But she’s certainly nothing like the Christ we read about in the Bible. “Nobody decent ever wins the games,” Katniss tells us in The Hunger Games: Catching Fire, and she understands that she’s not altogether decent. She’s willing to die, yes, but she’s willing to kill as well. She’s petty and brusque and, frankly, often clueless when it comes to the moves and countermoves swirling around her. She may be a Christ-like figure, but she’s no avatar of wise and kind Jesus.

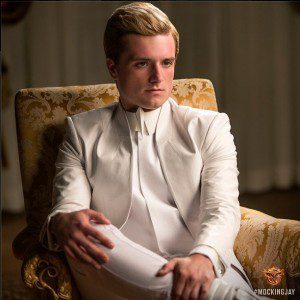

Peeta (Josh Hutcherson) is closer in soul and spirit to the Man from Nazareth. He was, simply, a baker’s son, defined not by his skill as a fighter (as Katniss is), but by his love. Time and time again he risks his life to save Kat. And even when Peeta’s captured by the Capitol in Mockingjay – Part 1, he still defends Katniss from afar. Katniss may be the Mockingjay, but, as Haymitch tells her, “You could live a thousand lifetimes and still not deserve (Peeta).”

Peeta (Josh Hutcherson) is closer in soul and spirit to the Man from Nazareth. He was, simply, a baker’s son, defined not by his skill as a fighter (as Katniss is), but by his love. Time and time again he risks his life to save Kat. And even when Peeta’s captured by the Capitol in Mockingjay – Part 1, he still defends Katniss from afar. Katniss may be the Mockingjay, but, as Haymitch tells her, “You could live a thousand lifetimes and still not deserve (Peeta).”

“Stay with me?” Katniss asks Peeta, both in Catching Fire and Mockingjay.

“Yeah,” Peeta tells her. “Always.” Just as Jesus always stays with us, no matter how bad or unlovable we are.

In the book Catching Fire, it’s interesting that Katniss spends a lazy afternoon, her head in Peeta’s lap, making a “crown of flowers.” Perhaps it’s an allusion to the crown of thorns Jesus wore—and the trials and torture that Peeta was soon to endure in the Capitol.

‘Course, Peeta isn’t exactly Jesus-like, either. He proved himself to be entirely human at the end of Mockingjay – Part 1, broken by tracker jacker venom and the unrelenting mental torture. He may have been willing to save Katniss at every turn. But as the movie ends, it’s pretty clear that Peeta’s the one in need of saving. This is no Easter story: It’s the story of two flawed people trying to do what’s right—and sometimes failing.

And that, perhaps, is the most Christian message of them all.

We’re told over and over in the New Testament to imitate Christ. “For to this you have been called, because Christ also suffered for you, leaving you an example, so that you might follow in his steps,” Peter says in 1 Peter. “Therefore be imitators of God, as beloved children,” Paul writes to the Ephesians. But as much as we try, we can’t get it just right. Sometimes our own flaws and selfishness can get in the way. Sometimes the world itself can squish all that goodness out of us. Even as we’re called to be like Jesus, we’ll always fall short.

Maybe that’s why the Bible stresses how important it is for us to live our lives as Christians in community—with people who can set us back on the right track when we go astray, who can encourage us when our hope slips away.

In Ecclesiastes 4:9-12, Paul writes this:

Two are better than one, because they have a good reward for their toil. For if they fall, one will lift up his fellow. But woe to him who is alone when he falls and has not another to lift him up! Again, if two lie together, they keep warm, but how can one keep warm alone? And though a man might prevail against one who is alone, two will withstand him—a threefold cord is not quickly broken.

When you look at The Hunger Games: Mockingjay – Part 1 through a Christian lens, you see a hint of a Christ-like figure, coming to save the day. You see an echo of Jesus, healing through love and grace. But mostly, you see a community of imperfect people working toward some much-needed personal and political redemption: Even as they all try to do the right thing—try to imitate Jesus, if you will—they can’t. Not alone, anyway. They need one another to serve as reminders. Each to sacrifice for the other, if need be. Because it’s only through hope and love and sacrifice that Katniss, Peeta and all of Panem can hope to find real freedom.

Just as it is with us.