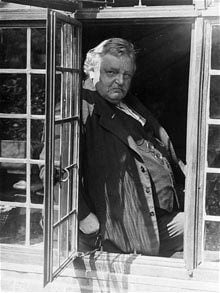

There is a move afoot to have G. K. Chesterton canonized as a Catholic saint. There’s a certain irony in this push to sainthood, given the man’s less-than-saintly appetites. He sometimes drank heavily (he allegedly joked that “one pint is enough, two pints is one too many, three pints isn’t half enough”), smoked heavily and ate heavily. Indeed, he weighed so much at the time of his death in 1936 that, when they put him in his coffin, it had to be carried out a second-story window rather than carried down the narrow stairs. More disturbing are the accusations that Chesterton may have been anti-Semitic (a charge that many of his supporters refute).

There is a move afoot to have G. K. Chesterton canonized as a Catholic saint. There’s a certain irony in this push to sainthood, given the man’s less-than-saintly appetites. He sometimes drank heavily (he allegedly joked that “one pint is enough, two pints is one too many, three pints isn’t half enough”), smoked heavily and ate heavily. Indeed, he weighed so much at the time of his death in 1936 that, when they put him in his coffin, it had to be carried out a second-story window rather than carried down the narrow stairs. More disturbing are the accusations that Chesterton may have been anti-Semitic (a charge that many of his supporters refute).

But if Chesterton’s candidacy for sainthood has a hint of paradox to it, that (paradoxically) fits the man. Chesterton knew his paradoxes, and it was one of the things he loved about Christianity. He wrote extensively about the faith’s many paradoxes—and when he was first investigating the faith, he marveled how its critics could find it so wrong in so many diametrically opposed ways: So Pollyannishly giving, according to one, so puritanically judgmental, according to another; So inclined to deny every joy, and yet so apt to indulge in wild extravagance. He writes in Orthodoxy:

I did not conclude that the attack on Christianity was all wrong. I only concluded that if Christianity was wrong, it was very wrong indeed. Such hostile horrors might be combined in one thing, but that thing must be very strange and solitary. There are men who are misers, and also spendthrifts; but they are rare. There are men sensual and also ascetic; but they are rare. But if this mass of mad contradictions really existed, quakerish and bloodthirsty, too gorgeous and too thread-bare, austere, yet pandering preposterously to the lust of the eye, the enemy of women and their foolish refuge, a solemn pessimist and a silly optimist, if this evil existed, then there was in this evil something quite supreme and unique.

Chesterton eventually concluded that some people saw Christianity as excessive (in one way or another) because the critics were themselves excessive (in one way or another), but did not deny that Christianity was indeed a bundle of contradictions. “Christianity got over the difficulty of combining furious opposites, by keeping them both, and keeping them both furious,” he wrote. “The Church was positive on both points. One can hardly think too little of one’s self. One can hardly think too much of one’s soul.”

We evangelicals don’t do saints. If we did, C.S. Lewis would’ve been the 20th century lay apologist more likely to be canonized. His Mere Christianity is the first book that many evangelicals thrust under the noses of our unbelieving friends. He’s a wonderful thinker and a fantastic writer and frankly, I think most of us feel smugly pleased that he’s part of our tribe. “We’ve got a Cambridge scholar and Narnia on our side! Hurrah!”

No disrespect for Lewis, but for me, Chesterton has been even more instrumental in my walk of faith. If Lewis’ Mere Christianity speaks to the reasonable 20th-century modernist in us—”Christianity makes sense, and this is why”—Chesterton’s Orthodoxy has a wild, witty 21st-century tang to it: It speaks of paradox and the power of story, of not just the truth of the faith, but its beauty and glory and inherent rightness. Mere Christianity speaks to the logician in me. Orthodoxy touches the poet.

And the guy’s a killer writer. He wrote everything—novels (The Man Who Was Thursday), short mysteries (he created the priestly detective Father Brown), essays, newspaper articles, encyclopedia entries, poetry and, of course, his works of Christian discourse. I haven’t read everything Chesterton wrote—because, really, given that he wrote 80 books and 4,000 essays, who could—but everything I have read has been pretty great. My favorite is Orthodoxy—I re-read or re-listen to it about every year—but all of his work seems filled with pithy, profound and sometimes zany quotes. My personal favorite is, “You cannot grow a beard in a moment of passion,” but he has others that make great refrigerator fodder:

“The Bible tells us to love our neighbors, and also to love our enemies; probably because generally they are the same people.”

“The Bible tells us to love our neighbors, and also to love our enemies; probably because generally they are the same people.”

“Just going to church doesn’t make you a Christian any more than standing in your garage makes you a car.”

“The word ‘good’ has many meanings. For example, if a man were to shoot his grandmother at a range of five hundred yards, I should call him a good shot, but not necessarily a good man.”

If Chesterton does become a saint, I would suggest he becomes the patron saint of Twitter. No one would be able to fill a feed so wonderfully.

And Chesterton is cool—like Madonna cool, Mr. Rogers cool, the guy in high school who could mingle with the jocks and the goths and the nerd and be pretty much liked by everyone. He’s a rebuttal to every disparaging (and sometimes true) stereotype slathered on Christians: He’s funny, charming, brilliant. Writes James Parker or The Atlantic:

Chesterton was a journalist; he was a metaphysician. He was a reactionary; he was a radical. He was a modernist, acutely alive to the rupture in consciousness that produced Eliot’s “The Hollow Men”; he was an anti-modernist (he hated Eliot’s “The Hollow Men”). He was a parochial Englishman and a post-Victorian gasbag; he was a mystic wedded to eternity. All of these cheerfully contradictory things are true, and none of them would matter in the slightest were it not for the final, resolving fact that he was a genius. Touched once by the live wire of his thought, you don’t forget it. And what is genius? Genius is Hammy the squirrel, in DreamWorks Animation’s 2006 classic Over the Hedge, five seconds after he gulps down an energy drink. The Earth stutters on its axis and then stops turning, the soundtrack comes to a soupy halt, and Hammy saunters through a sudden, humming immobility, past the transfixed pest-control guy and around the frozen laser beams of the lawn-alarm system. He is, of course, moving at incredible speed—but with supernatural nonchalance. His ecstatic velocity has put everything around him into the slowness and vagueness of a dream. That’s what geniuses do.

And one last telling trait: Even as he brazenly and hilariously took down some of his age’s greatest writers—Oscar Wilde, Edmund Bentley and George Bernard Shaw, among many others—he was on friendly terms with many of these self-same writers. Chesterton and Shaw got along particularly famously. When Chesterton came across his ever-so-skinny friend one day, he said, “I see there has been a famine in the land.” Shaw looked at Chesterton’s rotundity and quipped, “And I see he cause of it.”

Imagine, people who disagree so strongly with each other and still able to exhibit a strange, familiar cordiality. That’s something almost unheard of these days … and something I think that we could all use a little bit more of.

“The Christian ideal has not been tried and found wanting,” Chesterton famously said. “It has been found difficult and left untried.” I can’t say whether Chesterton embodied the Christian ideal, or at least embodied it enough for sainthood. (Even saints, after all, aren’t perfect.) But the fact that he embodied a different sort of Christian—a paradoxical contrast to the morose, incurious, judgmental Christian that so many people seem to picture when they think of the term—I’m very grateful for.