Frankenstein, the 1931 classic Universal monster movie, probably doesn’t have the oomph to terrify folks like it did back in the day. Most horror movies base their effectiveness on the fear of the unknown, and after 84 years, this flick is hardly that. Boris Karloff’s classic look as “the Monster” is so much a part of the culture that most 4-year-olds know what “Frankenstein” looks like.

But even though the first site of the Monster isn’t enough to cause hardened 21st-century moviegoers to faint dead away, the movie is still capable of tapping into a sense of real unease—a fear that we may feel more keenly now than in 1931. And it has an obvious spiritual bent to it, too—one that the movie itself addresses in its own introduction.

“We are about to unfold the story of Frankenstein, a man of science who sought to create a man after his own image without reckoning upon God,” actor Edward Van Sloan tells us.

Henry Frankenstein (Colin Clive) really had everything that a German noble could want: wealth, prestige, brains and a pretty fiancée, Elizabeth (Mae Clarke). Forget the Great Depression: For Dr. Frankenstein, the good times were still rolling along. But those sorts of earthbound pleasures weren’t enough for the guy: He wanted to do something extraordinary—and forbidden.

He and his assistant Fritz (Dwight Frye) began scouring graveyards and gallows for body parts: They weren’t too particular—just as long as they were fresh. Fritz steals a brain, too. Not a nice, normal one like Frankenstein had planned, but an abnormal brain from someone whose “life was one of brutality, violence and murder,” according to Doctor Waldman (Van Sloan).

Frankenstein stitches everything together (though, clearly, his sewing skills are not the greatest) and, during a climactic thunderstorm in a decaying ruin, he brings the Monster to life.

“It’s alive! In the name of God, now I know what it’s like to be God!”

It’s a pretty controversial statement—so controversial, in fact, that several states cut the line before allowing it to play.

Ironically, that well-meaning edit cut out much of the moral subtext of Frankenstein. Pretending to be God never works out well, the movie means to tell us. The Monster, once it gets up and moving, proves to be pretty unmanageable, and it’s not long before the thing escapes, kills people and eventually winds up trapped in a burning windmill, left to die.

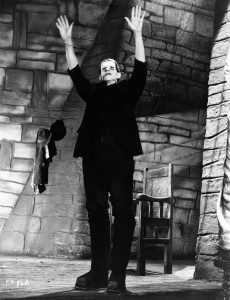

One of the greatest achievements of Frankenstein is that Karloff’s creature is more than the Monster: He’s a victim, too. Sure, he’s the size of a small car and cursed with an abnormal brain, but the Monster feels like a child—lost, bewildered, alone. He didn’t ask to be part of this twisted science experiment. One of the movie’s most poignant moments is watching the Monster reach for the light of the sun, then lower his arms in mute resignation when Dr. Frankenstein slowly covers it.

It seems so relevant in an age in which we, too, may be playing God a bit—attempting to create life in our own image.

We’re not really interested in stitching together a bunch of body parts these days, but we are very interested in artificial intelligence. While AI has moved incrementally forward, it’s still pretty rudimentary to the staggering flexibility of the human brain. Sure, computers can beat us at chess, but can that same computer cook an egg or flush a toilet? Nah. But some scientists are pushing computers to engage in “unsupervised learning”—the sort of learning we do really well—and it’s thought that this could lead to machines that can really, truly think. And once they start programming themselves, where does that leave us?

Potentially not in a very good place, speculates Stephen Hawking. While the scientist believes that AI has enormous potential, he worries that a little bug—an abnormality in the AI brain, if you will—could be devastating.

“A superintelligent AI will be extremely good at accomplishing its goals, and if those goals aren’t aligned with ours, we’re in trouble,” Hawking said on a Reddit conversation recently. “You’re probably not an evil ant-hater who steps on ants out of malice, but if you’re in charge of a hydroelectric green energy project and there’s an anthill in the region to be flooded, too bad for the ants. Let’s not place humanity in the position of those ants.”

And should that come to pass, of course, the fault wouldn’t really lie with our AI creations, but with us, their creators. Perhaps we can give them life. But can we give them light? Can we instill in them a sense of sacred awe and duty that, I think, is key to living life well? Can we give them a sense of morality, when the concept is so imperfect even in us? Writes author John C. Havens, “How will machines know what we value if we don’t know ourselves?”

In Frankenstein, maybe we see the real threat of AI: That maybe someday we’ll know how to create it, but we won’t really know how, or what, to teach it. Our very own flaws and failings will doom our greatest creations … and perhaps, by extension, ourselves.

There’ve been a lot of movies that have played on our unease of artificial intelligence and, by extension, playing God. But for my money, I don’t think any of them tackle the subject with the poignant horror of Frankenstein—a man who watched a scientific triumph turn tragic, a monster who was never given a chance to be anything but.