When I think of music’s great voices, I think of Ella Fitzgerald and Sarah Vaughan, Aretha Franklin and Adele.

Amy Winehouse was as good as any of ‘em.

She was a tiny girl with massive pipes—her voice brassy and buttery and frayed at the edges. She was at once behind and ahead of the times—a classic jazz singer who became a pop phenomenon, a women who claimed the past and made it her own. “She had the complete gift,” the great Tony Bennett said. When she died in 2011 at the age of 27, it wasn’t just she who lost that gift: It was all of us.

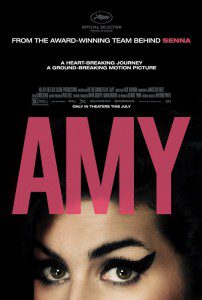

I was a Winehouse fan before I watched Amy, Asif Kapadia’s excellent documentary of her all-too-short career. I mourned her passing—or, at least, I mourned her as much as you can anyone whom you know through a handful of songs. But the doc brought out her life in tragic detail.

Kapadia introduces us to a teenage Amy, sucking on lollipops and laughing with her friends, already showcasing her chops by trilling through the “Happy Birthday” song. (Never has it sounded so bearable.) And as she begins her musical career, singing jazz standards at first and then through her first album, Frank, Winehouse looks and sounds and seems so normal. Besides her voice, the only thing that really differentiated the girl from lots of others was her love of the past: She adored the jazz greats from decades ago, and it was with them, not the pop idols of the late ‘90s and early 2000s, with whom she shared an affinity. Ironically, she sounds so mature when she’s younger—like a 50-year-old trapped in the body of a 19-year-old fledgling diva.

The doc suggests that Winehouse never had a desire to be famous. She wasn’t looking for the superstardom that knocked down her door.

“I don’t think I’m going to be at all famous,” she says. “I don’t think I could handle it. I’d probably go mad.”

Sadly, that’s what happened.

Amy unblinkingly traces Winehouse’s all-too-quick ascent to fame and parallel decline into a haze of booze and drugs. We need no spoiler warnings for this story: We know where it will end. Yet it’s still heartbreaking to watch it happen. You want to shout at the screen for her to get the help she needs. To cut loose the bad influences in her life. In a way, you want to take the singer in your arms and protect her—to push away the paparazzi that preyed upon her every boozy misstep, to wall her off from the evils of the world and let her sing. Just sing. It’s what she was put on this earth to do, Amy suggests: It was in song that she was happiest. Healthiest. The music fed her, just as her music fed us.

There is no single Iago in Amy, no one catalyst that ruined her. Amy points to many factors that contributed to the woman Winehouse was and the messed-up superstar she became. Amy’s father wasn’t around much when she was a kid, and her mother admits she wasn’t strong enough to rein in her headstrong daughter. Blake, Winehouse’s longtime boyfriend and short-time husband, introduced her to a lifestyle that included staggering amounts of alcohol and drugs. She resisted rehab—her most famous song is heartbreakingly autobiographical—but even when she finally got help, her own fame sabotaged the process. When she overdosed in 2007, her family and friends staged an intervention, bringing her to a Four Seasons Hotel to help her get clean. Within hours, the rest of the hotel rooms were filled with reporters, and pictures of her were plastered in the Sun.

It reminds us that, in a way, we too were complicit in her downfall. As a culture, we bought those issues of the Sun. We laughed at the late-night jokes at Winehouse’s expense. Instead of treating her spiral as a tragedy, we took it as a reality show—fodder for our supermarket tabloids and watercooler talks. Sometimes we forget that pop stars—the Biebers, the Bynes, the Lohans, the Winehouses—are people too.

But of course, Winehouse herself is to blame, as well. “Life teaches you really how to live it, if you live long enough,” Bennett says at the end of Amy. As much as her voice seemed so confident in song—soaring and diving and dancing along the bars—she couldn’t master the cadence of life. She didn’t give herself enough time.

Amy is a harsh movie, full of all sorts of content that I’d point out in a Plugged In review. But it’s a good movie, too—thoughtful and mindful. It is both an homage to greatness and a horrific cautionary tale. I’ve still got a documentary or two to see, but right now, I think it’s the best doc of the year.

Maybe about midway through the Oscar ceremony Feb. 28—when most of us are grabbing a snack and biding our time for the big awards—I bet we’ll hear the name Amy mentioned as a Best Documentary nominee. Maybe we’ll hear it again, as Asif Kapadia runs on stage to accept a statuette for his graceful, heartbreaking movie.

That honor, should it materialize, will be small recompense for the loss it chronicles. But at least it will remind us of a titanic talent in a fragile body. It will remind us what might’ve been.