We’re in the midst of a cascade of Christian movies right now. Risen. The Young Messiah (just chatted with the director on Friday). Miracles From Heaven is premiering this week. God’s Not Dead 2 releases April 1.

But let’s add one more flick to the list: Terrence Malick’s Knight of Cups.

Malick is one of the world’s most enigmatic directors. His movies feel like fever dreams or snippets of memory. He often works without a script. He’s a notoriously ruthless editor. (Actors Bill Pullman, Gary Oldman, Mickey Rourke, Lukas Haas, and Viggo Mortensen all worked on Malick’s war drama The Thin Red Line, but they ended up having their parts cut out.) Interviews with the guy are as rare as purple unicorns.

But for all Malick’s eccentricities, his work is strangely consistent: Its dreamlike quality, almost as if each movie was a string of moments half-remembered. Haunting imagery. And, most importantly, a deep thread of spirituality.

The Knight of Cups is perhaps Malick’s most religious movie yet. Indeed, the whole thing is an almost Medieval quest for faith.

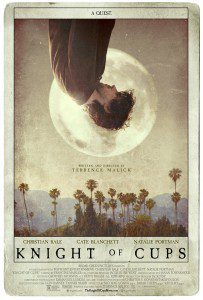

A Man Upside Down

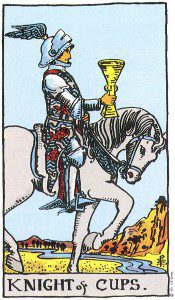

Knight of Cups takes its name from a card in the Tarot—a deck of cards used primarily these days for fortune telling. When you look at the traditional card, everything about the guy, from his white horse to his fish-bedecked cloak to the grail-like cup he carries, oozes symbolic spirituality. The card is also associated with emotion and romance.

Knight of Cups takes its name from a card in the Tarot—a deck of cards used primarily these days for fortune telling. When you look at the traditional card, everything about the guy, from his white horse to his fish-bedecked cloak to the grail-like cup he carries, oozes symbolic spirituality. The card is also associated with emotion and romance.

But flip the card upside-down, as we see in the poster, and the card’s positivity twists. “Reversed, the card represents unreliability and recklessness,” Wikipedia tells us. “It indicates fraud, false promises and trickery.” It also points to disappointment and disillusionment, according to fortune tellers: Things that began with so much promise end feeling empty. Hollow.

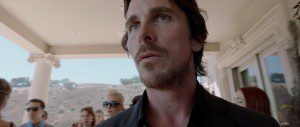

Rick, played by Christian Bale, is this upside-down Knight of Cups. He’s quite successful outwardly. As a mover-and-shaker within the entertainment industry, he lacks for little. When we first see him, he’s cruising down the highway, laughing with two pretty girls in tow. It’s suggested that his life is one long party … but in the early hours of the morning, when his fellow revelers have passed out on the floor, he stalks the floor of his flat like a ghost. “Where did I go wrong?” he wonders.

Rick, played by Christian Bale, is this upside-down Knight of Cups. He’s quite successful outwardly. As a mover-and-shaker within the entertainment industry, he lacks for little. When we first see him, he’s cruising down the highway, laughing with two pretty girls in tow. It’s suggested that his life is one long party … but in the early hours of the morning, when his fellow revelers have passed out on the floor, he stalks the floor of his flat like a ghost. “Where did I go wrong?” he wonders.

Rick’s father tells us (in Malick’s dreamy narrative mode) that Rick “drank from a cup that took away his memory. … He forgot that he was the son of a king.” Rick is supposed to be searching for a precious pearl. But instead he lost himself—not in the wilds of Judea, but the concrete deserts of Los Angeles, a city hemmed in by stony, parched lands.

Telling that the movie opens with a quote from John Bunyan’s classic Christian allegory Pilgrim’s Progress: “As I walked through the wilderness of this world, I lighted on a certain place where was a den; and I layed me down in the place to sleep: and as I slept, I dreamed a dream.” Christian, the main character in Pilgrim’s Progress, begins in the City of Destruction. And He, like Rick, are on a quest for something better.

Looking for Love in All the Wrong Places

Knight of Cups begins to sail through a series of dreamlike vignettes (separated into chapters named for other Tarot cards), Rick almost mutely exploring different facets of “meaning” as he travels.

He attends a sumptuous-but-vacuous party. The party’s host Tonio (played by Antonio Banderas) tells him that this—the food, the wealth, the laughter—is all there really is to hold onto in this world. There’s nothing beyond fleeting pleasure.

He visits a financial advisor in a gleaming tower of glass who promises to make Rick rich beyond his wildest dreams.

But the core of the story is found in Rick’s relationships with other women—and many of the women he meets seem to serve, at least in part, as metaphors for different branches of faith—different avenues of meaning.

Take, for instance, Karen (Teresa Palmer)—an exotic dancer whom Rick meets at a strip club. She’s fun, wild and carefree, and you can see a thread of exotic, polytheistic mysticism running through her relationship with Rick. As they walk, a man nearby playfully sticks a stone on his forehead, mimicking the Hindu “third eye,” which symbolizes a higher consciousness or enlightenment. (It’s telling that she raves about how her drug used “opened up this window for me … I call it the window of truth.”) They vacation at Caesar’s Palace in Las Vegas, where kitschy statues of Roman gods and goddesses stare serenely down at the proceedings—and where what looks like a Hindu shrine, strangely, shows up at a nearby pool.

Or there’s Helen (Freida Pinto), a serene model who seems to stretch and meditate beside a Buddha head. For the devout Buddhist, ultimate enlightenment is characterized by shucking off the extreme emotions of this world—the hatred, the jealousy, the passions that often trap us—in exchange for peaceful, unflappable serenity. So it makes sense that Helen, of all the women we meet, is the only one who rejects Rick’s amore. “I don’t want to wreck havoc in men’s lives anymore,” she tells him, suggesting they just be friends. And she leaves him at her door.

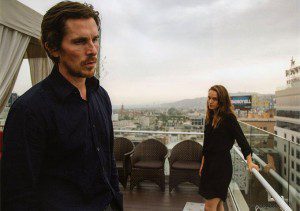

Elizabeth (Natalie Portman) is an interesting case. Described elsewhere as a woman from Rick’s past, the two embark on an affair even though Elizabeth is married. They visit a Zen garden and speak with a one-time monk there, but they later visit a museum filled with Classic Christian art—all of it, if memory serves, depicting Mary and Jesus. All these depictions of Mother and Child is particularly telling, since we learn that Elizabeth became pregnant herself. But unsure as to whose baby she was carrying—Rick or her husband’s—she aborted it. “I forget about it for a little while,” she says tearfully, “and then I remember.” The abortion terminates their relationship. Could it be that Malick is suggesting, with all those depictions of Mary and Jesus, that Elizabeth’s baby too was a gift from God? One that was rejected?

Coming Home

But even as Rick travels through these series of unfulfilling romances, he’s still dealing with—or perhaps remembering—his own difficult family: his destructive brother. His difficult father, Joseph (Brian Dennehy).

(It’s interesting to note that the biblical Joseph, the guy who became Pharaoh’s right-hand man in Egypt, also had two sons—Manasseh and Ephraim—and that Manasseh’s name means “forgetful,” a possible nod to Rick’s own state of forgetfulness.)

These vignettes with family thread throughout this religious quest. Rick quietly fumes at brother Barry, who seems intent on hurting or being hurt. Rick spends time with his father and watches as Joseph washes his hand in what appears to be a basin of blood. We see an angry confrontation in a dining room, complete with tears and smashed chairs.

These are clearly not easy people to relate to—and yet when Joseph’s disembodied voice comes to life, we hear in it a desire for peace and love and reconciliation. And it’s all grounded in Joseph’s faith.

We hear Joseph pray. We see him on his knees, begging for forgiveness. In one scene as we hear him speak, we see an injured pelican limp along a boardwalk—a deeply symbolic moment for any Medieval Catholics in the audience, given that the pelican was once a symbol of the Christian ideal of sacrifice. (In times gone past, Pelicans were thought to feed their own blood to their children.)

Joseph admits that he’s not been a perfect father. He’s not been a great Christian. But he says that even though he’s followed his own spiritual path like a drunken man, that doesn’t mean the path is the wrong one. Knight of Cups isn’t just about Rick’s search for meaning; it’s about Joseph trying to show him where meaning lies—where that precious pearl can be located.

Does Rick rediscover his father’s path? Does he seem willing to search for meaning via that time-honored faith? We’re never told explicitly, of course. This is a Terrence Malick movie, after all. But it is suggestive and hopeful.

Near the end of the movie, a priest tells someone—perhaps Rick—that suffering is a gift from God, not a curse, because suffering draws us closer to him. We see Rick wander through the scrublands of Southern California, which eerily look like the Judean wilderness. And then the next we know, he’s in his car, speeding down a highway to an unknown destination. The movie ends with Rick saying a single word: “Begin.”

Has he found his pearl? I doubt it. But he has woken from his dream. He has begun his search in earnest. He is, we’re led to believe, on a better path—a path his father wanted him to take. And whatever twists or turns it takes, I believe that Malick believes it ends at the foot of the cross.