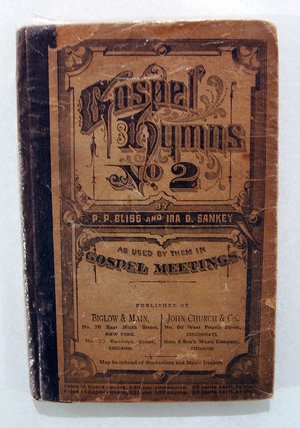

Amongst all the remarkable items in the Smithsonian’s collections—from the Hope Diamond to the Spirit of St. Louis, from Ben Franklin’s cane to Abe Lincoln’s hat—visitors might run across a modest, yellowed hymnal. It doesn’t look particularly impressive. But the hands which held it belong to the same person who will reportedly replace Andrew Jackson on the $20 bill: Harriet Tubman. The hymnal was one of Tubman’s dearest possessions, even though historians suspect she couldn’t even read it.

It’s a poignant reminder of the role faith played in Tubman’s life, and in her work.

Tubman was born a slave in the early 1800s (her death certificate says 1815, her tombstone 1820, and she herself said 1825) on a Maryland plantation. Known then as “Minty” Ross, the girl was raised on a steady dose of Bible stories told by her mother. Naturally, she gravitated toward the Old Testament, what with its many tales of captivity and deliverance.

Many suspect that Tubman’s fervent beliefs dovetailed with a terrible head injury she suffered as a child: When she refused to help hold a runaway slave, an overseer chucked a two-pound weight at the runaway that accidentally hit her in the head. The blow knocked her unconscious, but two days later she was back in the fields, “with blood and sweat rolling down my face until I couldn’t see,” she later said. She suffered seizures and sometimes appeared to fall unconscious, and she dealt with terrible headaches for the rest of her life. But she also experienced incredible visions—visions she believed came from God.

Many suspect that Tubman’s fervent beliefs dovetailed with a terrible head injury she suffered as a child: When she refused to help hold a runaway slave, an overseer chucked a two-pound weight at the runaway that accidentally hit her in the head. The blow knocked her unconscious, but two days later she was back in the fields, “with blood and sweat rolling down my face until I couldn’t see,” she later said. She suffered seizures and sometimes appeared to fall unconscious, and she dealt with terrible headaches for the rest of her life. But she also experienced incredible visions—visions she believed came from God.

Tubman successfully ran away in 1849, making her way to Philadelphia. Shortly thereafter, she joined the Underground Railroad herself to help others escape. Throughout her time as one of the Railroad’s “conductors,” she helped usher at least 300 slaves to freedom and once bragged that she’d never lost a passenger (though, Tubman admitted, she threatened to shoot nervous runaways a time or two).

And she always saw God as being right there at her side. Some passengers say that she’d often “consult with God” as they made their way north. “I always tole God, ‘I’m gwine [going] to hole stiddy on you, an’ you’ve got to see me through,'” she was quoted in Christian History. William Lloyd Garrison, the famous abolitionist, called her “Moses.”

And she used hymns—many of them found in her hymnal—as a way to transmit coded messages. “She’d sing ‘Steal Away to Jesus’ or ‘Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,’ and you would know it’s time to go,” Lonnie Bunch, director for the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, told NPR in 2010. “And so to be able to have a hymnal that has those songs in it that was hers is just pretty amazing.”

“I never met any person of any color who had more confidence in the voice of God,” abolitionist Thomas Garrett later said about her.

She never lost that confidence. Her last words were reportedly, “I go away to prepare a place for you.”

Now, the Treasury Department will be making a place for Tubman on the $20. It’s an honor richly deserved.