Asay: You’ve worked in the film industry for years, but this was your first directorial effort. Tell me about what drew you to this particular film.

Dreyer: That in some ways, the idea that a person sort of pops into your life and you have no idea why. You don’t know what lesson they are teaching you if they’re teaching you a lesson at all, but they have a profound impact on you.

Also, I did a lot of movies with a writer/director named Anthony Minghella [they worked together on such movies as The Talented Mr. Ripley and The English Patient, the latter which earned Minghella a Best Picture Oscar]. And he once wrote a play called “Cigarettes and Chocolate.” It’s about a woman who decides to stop talking. The entire narrative is about how everybody thinks she stopped talking because of them. She becomes a person that people keep confessing to. Every person in her life starts to confess something. And at the end, she says, two years ago, it was cigarettes, last year it was chocolate, but nothing’s been better than this. [She gave up talking for Lent].

And that’s kind of effect that Wren has. Everybody just wakes up in some way because she’s so private and so exclusive and so unusual.

Asay: The movie really is a lot about confession, isn’t it? And something about how writing down that confession—releasing it somehow—can free you.

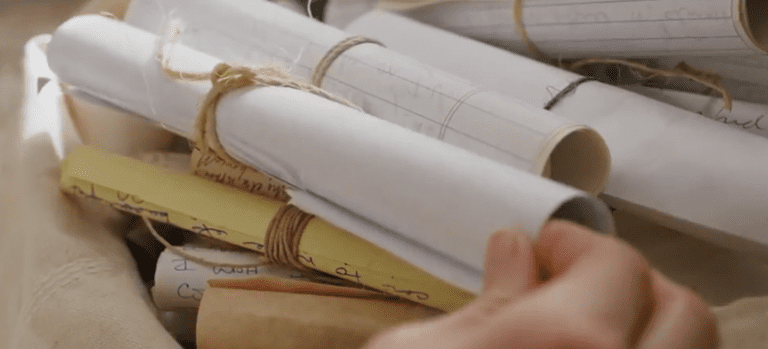

Dreyer: Yes. I think that’s one [aspect]. Look, I would love to single-handedly resurrect the post office and the idea of writing to people—not just to help yourself heal and to release something, but also to have a record.

Upon my parents death, I found all of these correspondence from the Second World War, just this mountain of material that’s so revealing and special and precious. I don’t know how that’s going to happen in the digital age, if it’s going to happen at all. There is empirical evidence that we write and work differently when we write through our hands [as opposed to] when we write through a typewriter. I think when you’re writing by hand, your thought process changes. There’s a lot more thinking [involved]. And I think it’s far more contemplative. And in being so, I think it can be far more truthful. You’re not spinning it. You’re not making it clever, you’re not making it funny.

And then there’s this idea that you need to release things. Jo Ann, she’s living on an edge, y’know? She’s hoping that no one’s ever going to find her [secrets], but she’s not getting any better. The progress only begins when she says, You know? I’m going to tell somebody. There’s a verbal confession and there’s a written confession. And they’re connected.

I’m a person who believes in prayer. I was once told very definitively that when you pray aloud, it’s much more meaningful than if you just say the prayer in your mind.

Asay: I don’t want to give too much away, but this movie has a lot of birds in it, which means the camera spends a lot of time looking up at the sky. And there was one scene—a delightful little moment—where you see a skywriter write out the letters “S-U-R,” which sure looked like a nod to the whole “Surrender Dorothy” scene in The Wizard of Oz. What was that about?

Dreyer: The Wizard of Oz is about as perfect a movie as you can make. If you watch it carefully, there’s almost nothing said or done that doesn’t further the story and take you to the next place. It’s just a magnificent lesson in how to tell a story. And since I had so many sky shots where I was going to put birds, or hoping for a flock of birds to fly by, I was just looking at the sky one day and thought, wouldn’t it be great? It was just a fun thing, and an homage to a film that I think is exceptional. You can watch it over and over and over.