Resurrection, the newest faith-based movie from Hollywood power couple Roma Downey and Mark Burnett (and just launched on Discovery+), takes a different tack than most movies about Jesus. While many concentrate on his life, teaching and crucifixion, they run the credits shortly thereafter. Mel Gibson’s bloody hit The Passion of the Christ spent most of its two-hour runtime on Christ’s suffering, and maybe 90 seconds on His triumphant return. And I get why. By then all the story’s innate tension and drama has been cleared up. Jesus’ resurrection makes for the ultimate happy ending: No need to belabor what comes after, right? Plus the hero of the story moves from being fully human to something … other. It’s kind of hard to grasp what that “other” really looks like. And honestly, details in the Bible are pretty sparse.

As such, Resurrection takes up a particularly daunting challenge: Infusing the important events after Jesus’ crucifixion with a little humanity. According to Downey, the key was to shift the focus to the drama’s all-too-human players.

“We know from Scripture that only John, the beloved, was at the foot of the cross with Mary Magdalene and Mary mother of Jesus,” Downey told me during an interview with Plugged In. “Judas had betrayed Jesus, but where were the 10 others? Where did they go?”

Downey and the movie’s other makers surmised they probably scattered–running away from the Roman authorities that might come after them next. Downey says they were probably terrified and heartbroken and, quite frankly, confused. The man they’d dedicated years of their lives to was dead now. They’d given up so much to follow Him. What were they going to do next, and without him?

“What we liked about crafting that story, is that it allows the audience to relate in ways that – they’ve been described here as real humans,” Downey said. “We see their humanity. We see their vulnerabilities, you know? And we realize that courage isn’t the absence of fear, that courage is having fear, but still stepping out.”

The movie feels as much the story of those disciples–Peter and John especially–as it does Jesus’ story. Peter makes for an especially interesting character, morphing from the terrified, despairing disciple who denied Jesus three times to the man who’d eventually become “the Rock” of a new faith.

Christians believe that Jesus is fully human and fully divine. That paradox has posed challenges to people telling Jesus’ story almost from the very beginning–balancing that humanity and divinity in a way that feels both real and reverent.

It’s not easy, and almost every movie or book or television show about Jesus eventually shades toward one side or the other. When I think of, say, 1977’s Jesus of Nazareth or even a lot of Downey and Burnett’s works, Christ feels pretty holy–and sometimes as a result, a bit less approachable. VidAngel’s runaway success The Chosen purposefully emphasizes Christ’s humanity, only hinting at His divinity. But that, of course, comes with its own problems.

And it strikes me that, often, artists and storytellers have tried to solve this conundrum through a bit of redirection. They turn our attention to those very human players that surrounded Jesus, and they let us see Christ through their eyes.

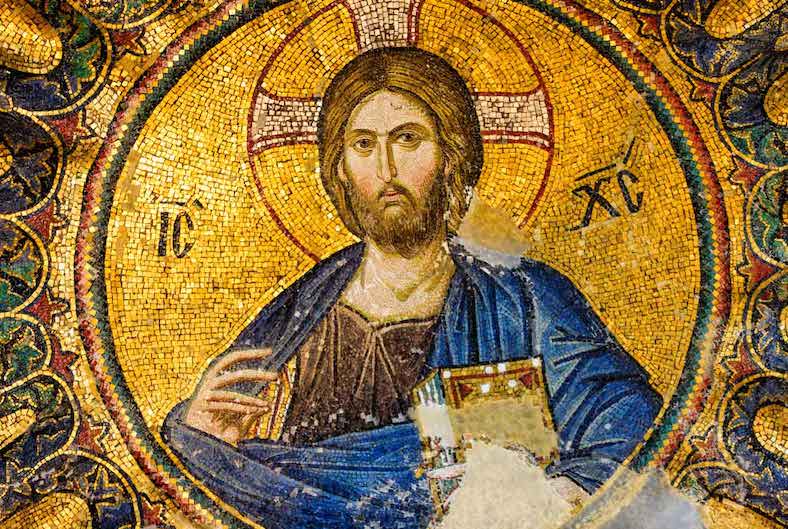

Back in the Middle Ages, depictions of Jesus and other biblical figures were symbolic and pretty stilted. Artists were all about representing the holiness and, in Jesus’ case, the divinity of their subjects, and telling a story through whatever symbolic objects they might decide to throw in there. They can be beautiful and powerful, as in this mosaic:

But Medieval artists stuck to a pretty rigid formula in how they depicted Jesus or any number of other biblical characters. This mosaic in Chora doesn’t look that different from a mosaic of Jesus found in the Hagia Sophia just down the road.

A Middle-age picture of Mother Mary with her baby Jesus in Italy would look much like one in France or the Byzantine Empire, with both mom and child looking remarkably peaceful and serene. Even depictions of Jesus’ crucifixion can feel chilly. It’s also interesting that many of these great works of Medieval art were put in places where normal people couldn’t reach them–at the altar, often, or in the case of these two mosaics, on the ceiling. Sure, Jesus here is depicted as sitting in heaven, enthroned and looking down on us. The ceiling’s a fitting place for Him in that case. But the positioning came with another, perhaps unintended, message: He was unreachable.

Indeed, many of these pictures depict players as especially holy–holier certainly than you and me. And while that might be true, and while that might offer a bit of an aspirational prod (“say your prayers, and maybe you can be in a stained glass window one day!”), it did keep the heroes of the faith and the everyday worshippers pretty distant from one another.

But that began to change.

Around the 13th century, a young artistic upstart named Giotto di Bondone started doing something different with his work: He infused a bit of humanity into it. Probably the most famous example is his Lamentation (Mourning of Christ).

Everyone still has halos. No one looks exactly true to nature. But when you look at the faces–particularly that of Mary, holding her child, and the angels above–you can see the grief etched on their faces. This is no formalized portrait, but an attempt to get to the real grief and heartbreak so many must’ve felt in that moment.

Giotto helped kickstart the Renaissance with this work, where artists pushed past formalized symbolism and tried to portray things as they looked to you and me, humanizing even the most solemn religious stories as they did so.

I was reminded of this picture, actually, while talking with Downey, when I asked her what moved her about the movie especially. Even though the movie deals mostly with the events after Jesus’ death, Downey returned to Jesus’ crucifixion, which takes place just 15-20 minutes in.

“I don’t know whether it’s because I’m a mother and I have a mother’s heart, but I never can watch this movie, or any movie, that has Mary, the mother of Jesus standing and remaining at the foot of the cross,” she told me. “Because you can’t imagine the strength and courage needed to see your child being murdered before your eyes. And yet I feel certain that she stood there, looking up, so that when He would look down, he would see the face of love. That the last thing Jesus would see from His earthly life would be the loving eyes of His mother.”

The divinity we find in Jesus is so important. It’s what our faith is built on, after all. But it’s the humanity that brings it home–the human face that God wore for us, and how He interacted with the fallen, fallible humans all around us. That’s something that Resurrection reminded me of, and something I’m mindful as Holy Week begins. It’s not just the story of how Christ died, but how He lived. Just like us.