You can’t deny the power, artistry and sheer entertainment value of Ryan Coogler’s Sinners. The film manages to balance horror and humor as well as any. Michael B. Jordan—playing the gangster twins Smoke and Stack—is at his charismatic best. And the music? It swings from foot-pounding blues numbers to tender Irish ballads–transcending the window-dressing treatment music often get and deftly informing both what Sinners says and how it feels.

And that’s the point. Sinners is about music: Not just its beauty, or its knack to get your toes to tapping or your eyes to get a bit misty, but its literal power.

Music, the film tells us, can span barriers of space and time. It can burrow into our very being and somehow pull us into another state of being. Music brings joy—not just a water-downed good time, but a transcendent sense of being one with the earth and sky and the people all around. Sinners suggests that great music might be as close to heaven as we’ll likely get.

But that’s a problem, too—both for the people in the movie, and those watching it.

‘The Children of the Night. What Music They Make’

People have long understood the power of music. In Greek mythology, Amphion was said to have built the city of Thebes by playing his lyre. In Chinese myth, the demigod Fuxi was said to have brought order to humanity through his music. Plato once said that “rhythm and harmony find their way into the inmost soul and take strongest hold upon it.”

And in my own faith tradition, Israel’s King David was a master composer. “Make a joyful noise unto the Lord, all the earth” he wrote in Psalm 98, imploring the rivers to clap their hands and the hills sing for joy.

Music is a gift. And that gift finds its finest expression in honoring God, the Giver.

But Sinners takes a different tack.

Enter Preacher Boy, a.k.a. Sammie (played by Miles Caton). He’s a sharecropper in Jim Crow-era Mississippi and son of a local minister who (we’re told) gave Sammie his first Bible when he was 8. But while Sammie doesn’t have anything against the Good Book, his first love is good blues. He’ll sing and play any chance he gets. And he gets his chance when Smoke and Stack come back to town.

The brothers made their money in Chicago, working with a pretty prominent mobster up north. But they’re back in Mississippi now, hoping to open a “juke joint” in an old sugar mill. Their nephew, Sammie, just might be one of the joint’s big attractions—even if his Bible-thumping dad doesn’t approve.

“You keep dancing with the devil,” Sammie’s father warns him, “One day he’s going to follow you home.”

But Christianity isn’t the only spiritual system represented here. We’re also given a window into the wide-ranging beliefs found in pre-colonial Africa—beliefs rooted in and represented by music. We’re told early on that music had the power to link past and present and future. But because of its strength, it also tended to attract darker forces.

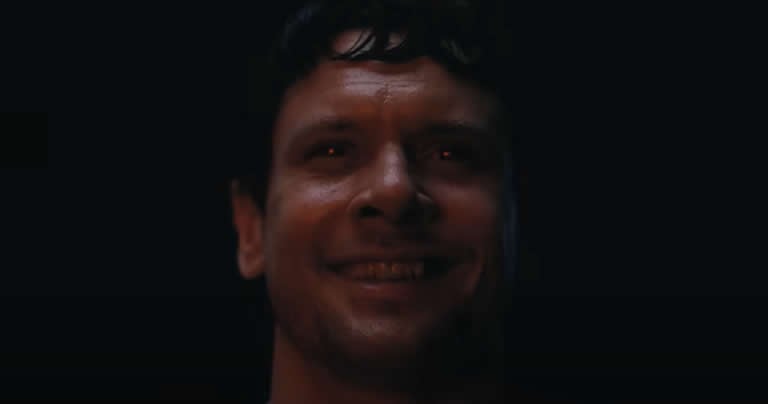

Those darker forces come a-calling, in the form of an Irish vampire who recently escaped a posse of do-gooding Choctaw Native Americans. He’s taken in by a couple of KKK members. And in thanks, he quickly turns them into vampires as well. And when they apparently hear the sound of Sammie’s music during the juke joint’s opening night, they pay a visit—disguising their true natures and saying they simply want to dance.

But they’re kept out, mainly because of their skin color. It’s a bit of reverse discrimination, but Smoke has reason for being discriminating. If one of the visitors got their toes stepped on, he says, no telling where it would lead.

Deeper Themes

Now let’s back up just a bit and acknowledge the obvious: Coogler is exploring far deeper themes than just whether a handful of vampires dine on a bunch of music lovers. Racism forms one of Sinners’ massive undercurrents. And superficially, it feels pretty—well, black-and-white. The vampires are white. Their intended victims are black.

Perhaps it’s telling that the one character who can live in both worlds—Mary, played by Hailee Steinfeld—is the unwitting conduit to the bloody drama that follows. She goes out to suss out the visitors’ true intentions and is instead turned into a bloodsucker herself. Superficially, Sinners seems to suggest that the lure of racial harmony is a lie.

But Coogler’s racial nuances are far more complex, and the first hint is Sammie’s beloved guitar—supposedly owned by legendary bluesman Charley Patton. Little is known about Patton, but historians believe that he was part Black, part Caucasian (perhaps Irish) and part Choctaw—all lineages that figure prominently in Sinners. And our Irish vampire suggests that his people, too, were subjected by others. And a primary tool for that subjugation? Christianity.

Biting Commentary

When Sammie begins reciting the Lord’s Prayer, the vampire—and all his associated bloodsuckers—join in. He tells Sammie that even though the Christian faith was imposed on he and his people (which, if he’s speaking of Ireland itself, that conversion would extend as far back as the 5th century), the words still bring him comfort.

That’s not the first time that Christianity has been referenced as something of a literal imposition. Delta Slim—a grizzled, often drunk old blues player—tells Sammie that Christianity was forced on Blacks. But the blues are something that they can call their own.

This is interesting—especially given Coogler’s Christian faith. Coogler has identified himself as Christian—reared in the Baptist church and educated in Catholic schools. And throughout his work, faith and religion has continually found its way in his works. I loved what Coogler did with faith in the Black Panther movies, especially in Black Panther: Wakanda Forever.

But in Sinners, Christianity is framed as something “other,” something from the outside—as foreign and perhaps as corrupting as vampirism itself. It stands in as almost a second antagonist: A corruptive force that African Americans never asked for.

Certainly, this condemnation of the Christian faith isn’t universal. The Choktaw Indians invoke the name of God as a blessing. But the faith takes a backseat to magic rooted in traditional African beliefs: The story’s seemingly most knowledgeable vampire killer doles out herbs before going to the doomed juke joint. We learn that she gave Smoke a protective “mojo” bag, and Annie thinks that her gift protected Smoke all those years up north.

But Annie’s magic itself feels far less potent than the magic of music. In one gloriously energetic sequence, Sammie’s artistry draws in other musicians from across cultures and through time, from African drummers to Asian dancers to American rock-and-rollers, all sharing the spiritual stage with Sammie, and their collective jam appears, for a moment, to literally burn the house down.

This Little Light

The character Sammie was inspired by Robert Johnson, who (legend has it) went to a Mississippi crossroad, met with the Devil and sold his soul in exchange for mastery of the blues.

Regardless, Coogler’s Sinners tells us that Johnson made the right choice. Music, not faith, is the secret sauce of salvation. And when Sammie’s father begs Sammie to renounce his music and fully embrace Christianity, he leaves and follows his own path.

As if to underline that choice, Coogler bookends Sinners with the song “This Little Light of Mine.”

We hear it first in the church of Sammie’s father, sung by children dressed in white. And here, the “light” is meant to be the light of faith. The light of God. It’s taken from Jesus’ Parable of the Lamp, where Jesus implores His listeners to “let your light shine before others, so that they may see your good works and give glory to your Father who is in heaven.”

But when Sammie sings it himself at the very end of the film, it comes with a very different message.

In part, that message reflects how the song became a familiar feature of the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s—a beautiful protest against those who wanted to silence African Americans. Given Sinners’ understandable preoccupation with racial issues, Coogler surely intended this connection.

But more than that, Sammie is singing about himself: His own talents, his own songs, his own music. No one—not vampires, not racist and certainly not Christianity itself—will keep Sammie from letting his talent roar. Sammie makes a joyful noise to himself.

For me, “This Little Light of Mine” makes for a dispiriting coda to Sinners—this glorification to self. Our “gifts” are called gifts for a reason, after all. If we’re blessed with a talent for singing, or playing, or painting, or directing, we can’t take all the credit for it. Sure, we may hone these gifts through time and hard work. But those gifts come from elsewhere. They come, I’d argue, from above.

And everyone knows that when we’re given a gift, we should always write a thank-you card. We should always acknowledge the giver.

Good movies don’t often preach: They ask questions. They play with ideas. They hit nerves for the sake of conversation. And Sinners is a good movie by a great director. But when I think of Sinners in relation to some of Coogler’s other works, this film seems to embrace the ethos of Erik Killmonger, the antagonist in Black Panther, than T’Challa, its hero. It encourages a worship of self, not of something greater. And that, true to the movie’s name, is the root of all sin.