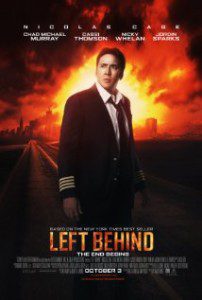

I was reading an interesting article from the New York Post regarding the surge of reasonably successful Christian movies, the newspaper’s eye fixed firmly on the release of the Left Behind remake. “After years of releasing shoddy products featuring has-beens like Kirk Cameron, the Christian film industry is upping its game in an attempt to win a crossover audience,” the Post’s Reed Tucker writes. “Is faith-based cinema about to go truly mainstream?”

I was reading an interesting article from the New York Post regarding the surge of reasonably successful Christian movies, the newspaper’s eye fixed firmly on the release of the Left Behind remake. “After years of releasing shoddy products featuring has-beens like Kirk Cameron, the Christian film industry is upping its game in an attempt to win a crossover audience,” the Post’s Reed Tucker writes. “Is faith-based cinema about to go truly mainstream?”

The answer is no, not yet. Or no, not ever. Or yes, it already has.

See, to really answer that question, you have to ask yourself another: Just what is faith-based cinema?

The typical definition of Christian cinema feels strangely like how most people define obscenity: We know it when we see it. Left Behind, based on a book that took the evangelical Christian subculture by storm, is most obviously a Christian movie—one made by Christians, for Christians, and in the hopes that other people will become Christian. It was certainly a Christian movie when it was made for the first time in 2000, starring the Post-maligned Kirk Cameron. It felt like a movie that only Christians would like.

That’s been the rap (not always altogether fair) on Christian moviemaking for decades now: Deeply sincere movies made through subpar methods. Christian films lack the budget for huge special effects or top-notch stars. The plots are preachy, the screenplays one-dimensional. While I’ve had the opportunity to see gradual and substantial improvement in Christian filmmaking from my vantage point at Plugged In over the last several years, those improvements are perhaps not quite as obvious to those outside our little subculture.

And so well-meaning critics of Christian moviemaking say that, for the craft to break into the mainstream, it needs to be stocked with A-list talent … like, maybe, 2012’s Les Miserables, a musical starring Hugh Jackman, Anne Hathaway and Russell Crowe that earned more than $441 million worldwide and was nominated for eight Academy Awards (winning three).

And so well-meaning critics of Christian moviemaking say that, for the craft to break into the mainstream, it needs to be stocked with A-list talent … like, maybe, 2012’s Les Miserables, a musical starring Hugh Jackman, Anne Hathaway and Russell Crowe that earned more than $441 million worldwide and was nominated for eight Academy Awards (winning three).

‘Course, Les Mis is an explicitly Christian story of sin and redemption, which I’d argue makes it a “faith-based” movie already, and one that already saw quite a bit of mainstream success.

They’ll argue that faith-based movies need to have state-of-the-art digital effects … like the breathtaking 2012 film Life of Pi, described by Roger Ebert as “a miraculous achievement of storytelling and a landmark of visual mastery,” a $485 million worldwide blockbuster and was nominated for 11 Academy Awards (winning four).

Interesting that Life of Pi is completely predicated on the subject of faith, as well—not explicitly Christian, granted, but certainly one with a number of Christian themes.

They’ll say that faith-based films need to be not-so-strident and more morally complex … perhaps like last year’s Oscar-nominated Philomena (which focuses on a woman of deep faith as she tries to learn what became of her son who was taken from her). They need to be harsher and grittier … like Children of Men, a twisted, R-rated retelling of the Nativity story that’s considered one of the 21st century’s best films.

When you really look at the history of cinema, faith is not some rare interloper. Faith, spirituality and even explicitly Christian stories have been a part of mainstream cinema since the beginning of the art form. In 1959, Ben Hur—a Christian story so explicit that it makes Left Behind look subtle—won 11 Academy Awards. Chariots of Fire, the Best Picture winner from 1981, was in large measure the story of Eric Liddell, a deeply religious Olympian who refused to compete in his best event because a heat landed on a Sunday. We’re not talking about films with a subtle faith-tinged subtext, here. We’re talking about movies predicated largely on faith.

When you really look at the history of cinema, faith is not some rare interloper. Faith, spirituality and even explicitly Christian stories have been a part of mainstream cinema since the beginning of the art form. In 1959, Ben Hur—a Christian story so explicit that it makes Left Behind look subtle—won 11 Academy Awards. Chariots of Fire, the Best Picture winner from 1981, was in large measure the story of Eric Liddell, a deeply religious Olympian who refused to compete in his best event because a heat landed on a Sunday. We’re not talking about films with a subtle faith-tinged subtext, here. We’re talking about movies predicated largely on faith.

While these movies had spiritual stories to tell, they weren’t necessarily told with the sole objective of converting the audience. And perhaps that’s closer to Tucker’s definition of “faith-based” cinema: Movies made by Christians that serve, in a way, the same purpose that a church service does.

I think that those sorts of “churchy” movies, while they will always be with us and will continue to get better, will also largely be sequestered to Christian audiences—no matter how big the cast or how spectacular the effects. The story’s the thing that makes for a winning movie, in my opinion. And while faith can be a huge component of a successful story, that story will never look much like a church service.