If one wishes to make lots of money in this world, one does not major in English lit.

If one wishes to make lots of money in this world, one does not major in English lit.

But it does have its benefits. For one, it can allow you to criticize your co-workers in creative ways. (“Don’t you dare go all Harold Skimpole on me!” I’ve been known to say.) You stand a better chance of winning in Trivial Pursuit. And it gives you the inclination to tease out strange parallels between centuries-old classics and teen-oriented sci-fi flicks.

Take, for instance, Divergent.

The movie centers on a girl named Beatrice, born into a dystopian civilization dominated by a stringent caste system. Five different castes, or factions, dominate life in this broken-down version of Chicago: Abnegation, the city’s selfless governors; Amity, its peaceful farmers; Candor and its honest judges and legal eagles; Dauntless, the city’s brave defenders, and Erudite, made of intelligent scientists and the ilk. Beatrice was born in the Abnegation faction, but people have the freedom to select the faction they feel is right for them—aided by a test that points them in the right direction.

But when Beatrice is tested, she learns she could actually fit in any one of three castes: Abnegation, Dauntless or Erudite. That makes her Divergent—and, some would say, extremely dangerous. Thing is, Divergents can’t be controlled nearly as easily as people who fit in one of the standard factions, so you never know what sort of problems they might cause.

I found all that quite interesting when I watched Divergent for a Plugged In Movie Night. But I also was really fascinated by the name given to Woodley’s character: Beatrice.

Now, I don’t know if you need to be an English wonk to know that Beatrice is a prime character in Dante’s Divine Comedy. But it doesn’t hurt.

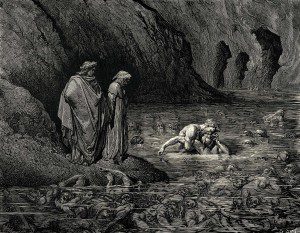

Written in the 14th Century, The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri is considered by some to be the Renaissance’s first literary work. It chronicles Dante’s allegorical journey through hell, purgatory and heaven (meeting many famous saints and sinners along the way). And throughout his afterlife travels, he’s encouraged and sometimes led by a saintly lady named Beatrice (a real girl whom Dante loved mostly from afar). But being a heavenly, um, being, she can’t go down to hell. For that, Beatrice entrusts Virgil, considered by Dante to be one of the pre-Christian world’s smartest people. And so together, in Dante’s Inferno, Dante and Virgil crawl into the Pit of Hell.

Written in the 14th Century, The Divine Comedy by Dante Alighieri is considered by some to be the Renaissance’s first literary work. It chronicles Dante’s allegorical journey through hell, purgatory and heaven (meeting many famous saints and sinners along the way). And throughout his afterlife travels, he’s encouraged and sometimes led by a saintly lady named Beatrice (a real girl whom Dante loved mostly from afar). But being a heavenly, um, being, she can’t go down to hell. For that, Beatrice entrusts Virgil, considered by Dante to be one of the pre-Christian world’s smartest people. And so together, in Dante’s Inferno, Dante and Virgil crawl into the Pit of Hell.

The Beatrice in Divergent is not synonymous with the Beatrice in Dante’s work. While Beatrice’s roots in Abnegation are suggestive, she’s a little more like Dante, confused and adrift and not really knowing who she was or where her place in it might be. While Dante found himself in a dark and frightening forest, Beatrice was born into a broken city. And in her own way, she’s lost.

And, like Dante, she begins her search for meaning and purpose in the Pit.

That’s what the people in Dauntless call their headquarters and training grounds. Like Dante’s hell, the Pit is a place of trial and pain and fear. And like Dante, Beatrice (who has, interestingly enough, changed her name to “Tris” to symbolically break from her more saintly, Abnegation-like roots) is expected to learn from these trials and torments. She is not completely at home there. But as her journey continues, she toughens up and learns to deal—just like Dante does.

Now, recall the caste divisions that Tris did not choose: Abnegation, a caste that fits her spiritual beginnings and that Dante’s Beatrice would’ve found quite appealing; and Erudite, which would seem to carry with it echoes of Dante’s super-smart Virgil. She carries with her, it would seem, her own guides.

Furthermore, Tris’ three factions—Dauntless, Erudite and Abnegation—may be somewhat analogous to states of the human psyche—what Sigmund Freud would classify as the id, ego and super-ego. But they also hint of the parts that I think make up the human soul. Dauntless might represent our more animalistic, evolutionary instincts—our drive to survive live and even dominate. Erudite is the stuff that makes us human—our intelligence and ability to problem solve, our growing empirical understanding of the world around us. For Dante, Virgil represents the highest pinnacle of purely human understanding and achievement that one can reach without divine illumination. And Abnegation, of course, hints at our Divine beginnings—the things that represent the better angels of our nature: Our ability to be generous and merciful, to care for others before we care for ourselves.

Furthermore, Tris’ three factions—Dauntless, Erudite and Abnegation—may be somewhat analogous to states of the human psyche—what Sigmund Freud would classify as the id, ego and super-ego. But they also hint of the parts that I think make up the human soul. Dauntless might represent our more animalistic, evolutionary instincts—our drive to survive live and even dominate. Erudite is the stuff that makes us human—our intelligence and ability to problem solve, our growing empirical understanding of the world around us. For Dante, Virgil represents the highest pinnacle of purely human understanding and achievement that one can reach without divine illumination. And Abnegation, of course, hints at our Divine beginnings—the things that represent the better angels of our nature: Our ability to be generous and merciful, to care for others before we care for ourselves.

So it’s also interesting that those who fell into the Erudite faction were mystified by Abnegation. The faction’s penchant for looking to the needs of others before themselves just, from an Erudite point of view, doesn’t make sense. In my Movie Night, I suggested the tension between Erudite and Abnegation holds an echo of the science vs. faith arguments we have in our own world: Faith, for the unfaithful, can seem irrational. And in some ways it is. And yet there’s a beauty and a benefit to it, as well, and a truth that cannot really be measured by empirical means.

Now, I don’t know if any of this was on the mind of author Veronica Roth when she wrote Divergent, or whether the next two books in the series (Insurgent and Allegiant) might hold whiffs of the rest of Dante’s Divine Comedy (Purgatorio and Paradiso). But Roth, a Christian, certainly imbued Tris with both the heart of a spiritual quester, like Dante, and a savior, like Beatrice.