Part III of Caves, Cloisters and Temples

Part I is here. Part II is here.

I am an ordinance worker in the Provo Temple. I get to work with young women, and sometimes older women, who are going through the temple for the first time. I explain to them the meaning of their garments, and promise that they will be protected if they wear them. (I consider this protection to be more spiritual than physical.) I also pronounce supernal blessings on the living who represent the dead.

Two weeks ago, I served a weeping patron who was a Spanish speaker. She represented the name on the card, which was a Mexican name. Though I speak Spanish, I did the initiatory ordinance in English. Afterwards, I asked the patron (in Spanish) if she was related to this woman whose name we had spoken during the ordinance. “Es mi abuela,” she said. Her grandmother. So she had memories of her. Likely, the memories had been polished by the passage of time.

I have contemplated this proxy work. On a superficial level, we who stand in for the dead, or we who wash, anoint, and clothe (all done symbolically and modestly and with reference to Exodus 40) are attempting the impossible–offering the temple promises and blessings to uncountable millions in every island and inlet of the world. It might seem a futile and arrogant endeavor. But there is importance to the rituals which we will certainly overlook if we are viewing it only as name transfer–from cemetery plot to temple record.

Time disappears in the temple. When I help with proxy initiatory ordinances, I am looking at a human life without knowing what pains or handicaps that human endured. Did they have OCD? Depression? What were their joys? Their final thoughts? Their regrets? Their secrets? I work with the names in the present and speak down the years, addressing them as though I had interrupted their worst moments with a blessing of hope and forgiveness, as though every pain they suffered were now sanctified, re-lived within the promises of redemption. I speak grace into the hollows of their mortal moments, just as I have felt grace being shed upon me at times when I was near collapse. As I review my times of need, I remember the grace, not the pain. Even if I didn’t believe the work had any effect on those who have passed on, the act of pronouncing blessings without any sense of chronology is itself remarkable, a statement of faith. And the words of the ordinances are ones I love and am glad to have memorized, just as I am glad I can quote certain scriptures, Shakespeare, Blake.

But I do believe the work has an effect.

In initiatory, we work with individual names. None is attached to family associations in this part of the endowment. Each woman, representing another, is prepared for the womanly priesthood order, which is separate from but synergized by the male order. (Marriage is the highest “order of priesthood”.) During the endowment, she will be robed as a priestess and as a bride. In a frequently misunderstood symbolic act, she will veil her face. Some have assumed that this is to keep men from being distracted by the woman’s beauty. But there are always layers of meaning, and we discover new depths, new meanings as we age and as we serve.

Consider the traditions in early Judaism and Christianity involving veils.

First, remember when Moses veiled his face, and when he did not:

29 When Moses came down from Mount Sinai with the two tablets of the covenant law in his hands, he was not aware that his face was radiant because he had spoken with the Lord. 30 When Aaron and all the Israelites saw Moses, his face was radiant, and they were afraid to come near him. 31 But Moses called to them; so Aaron and all the leaders of the community came back to him, and he spoke to them. 32 Afterward all the Israelites came near him, and he gave them all the commands the Lord had given him on Mount Sinai.

33 When Moses finished speaking to them, he put a veil over his face. 34 But whenever he entered the Lord’s presence to speak with him, he removed the veil until he came out. And when he came out and told the Israelites what he had been commanded, 35 they saw that his face was radiant. Then Moses would put the veil back over his face until he went in to speak with the Lord. (Exodus 34, NIV)

Consider next the traditional Jewish wedding:

The groom brings down the veil over the bride’s face, reminiscent of Rebeccah’s covering her face with her veil upon seeing Isaac before marriage. The veiling impresses upon the Kallah her duty to live up to Jewish ideals of modesty and reminds others that in her status as a married woman she will be absolutely unapproachable by other men. The covering of the face symbolizes the modesty, dignity and chastity which characterizes the virtue of Jewish womanhood.

The Jewish woman, being the strength and pillar of the home, is also reflected in these signs of modesty and dignity which will be the pillars and the foundation of their new home. With the above, she will fill her home (the sanctuary of the individual’s holy Temple) with security and warmth.

In temple weddings, the bride’s face is not veiled. Nobody gives her away. She and the groom come as individuals (usually holding hands) to the altar, prepared to give and to receive one another. It is an act of volition and supreme courage, though most don’t recognize how courageous their marriage was until they have spent years in it.

Both male and female will be symbolically clothed in the temple, an act which reminds me of the beautiful “Hymn of the Pearl”, written in the second century A.D. The wandering son, who has forgotten his royal heritage, receives a letter from his heavenly parents: “Remember thy Glorious robe,Thy splendid mantle remember, To put on and wear as adornment,When thy name may be read in the Book of the Heroes.”

I have heard some refer cynically to the endowment as glorified Masonic rites. Certainly there are commonalities between Masonry and the endowment. But there is one glaring difference between them: no woman was ever admitted into the rituals of the Masonic temple. Joseph Smith, on the other hand, was much maligned for offering the endowment to men and women alike. The significance of this cannot be overstated. What he did was utterly revolutionary and boldly egalitarian.

I have heard complaints about phrases in the temple liturgy, but none has detracted from my own experience there.

I was endowed in 1979. Upon entering the Provo Temple, I was overwhelmed by the spirit of the place, the holiness. If I imagined its divinity because I had been prepared to do so, I have no problem with that. Imagination is a vital part of spirituality. We open our minds to every good possibility. I don’t believe it was simply my imagination, though. I find that whenever I receive spiritual insight, my capacity to love and my ability to forgive are enlarged. I become a participant more than a star, and aware of the uniqueness of each person around me. Of course, I was receiving the story for the first time, and I found it beautiful and thought-provoking. The experience re-translated many scriptures for me, though my most recent translations have gone far deeper than my early ones did.

It is no surprise to me that others outside Mormonism have had insights about the Bible’s creation chapters similar to what we Mormons understand.

This is by Jeff Morrow (Seton University): “Genesis 1-3, in its account of creation, presents the cosmos as one large temple, the Garden of Eden as the Holy of Holies, and the human person as made for worship. The very content and structure of Genesis 1-3 is in a very real sense liturgical; the seventh day is creation’s high point.”

The renowned theologian Margaret Barker observed this:

The Genesis story of the six days of Creation also described the ceremonial building of the temple, which was in two parts, divided by the great curtain. The outer area represented the visible material world [the Garden of Eden] and the inner

part was the holy of holies, the invisible world of the Glory of God and the angels [heaven]. The curtain represented matter concealing the Glory of God from human eyes, but the holy of holies in the heart of the temple showed that God was at the heart of Creation. All temple worship concerned the relationship of the Creation to God – praise, thanksgiving, asking for forgiveness – and the whole of the visible world was thought to be a temple where human beings were the priests. ‘Adam’ [the

name simply means a human] was put into Eden to ‘serve’ it and to ‘preserve’ it, two Hebrew words which also mean worship in the temple and preserving the teachings

I came first to the temple as a daughter, my mother at my side, my father within my sight. I came next as a wife, looking for some direction in a marriage which had gone horribly wrong. I attended once as a newly divorced woman and broke down in my car after a worker told me I should have worn nylons to the temple. I had done so many things wrong that this chastisement was more than I could bear–particularly at the place where I was seeking solace. Now, as a worker, I retain that sensitivity, understanding that every patron is bearing burdens. There are no more rules about whether or not we should wear nylons to attend the temple. No more rules about whether our earrings can dangle. We are counseled over and over again to make each patron’s time in the temple all it should be. We do not scold. I personally do not even frown. In fact, by the end of my shift, my mouth hurts from smiling. But I bear that tiny pain gladly. I want each woman I serve to feel some small communication of love from me.

I have come to the temple as a mother of struggling children, and I have received revelation. The temple is my Sacred Grove. I understand that not everyone responds to it as I do. I love what I find in the temple, every new discovery or insight, and I know that others find similar inspiration elsewhere–in the discovery of new leaves, wildflowers, the quick movement of a deer.

I love the meditative moments that begin the endowment. I love the instruction. I love the symbols–and wrote judiciously about them years ago thus: “If I could, I would dance the temple rituals with uplifted arms and jubilant music. I would bless and receive blessings; I would praise and thank God with every part of my body.”

I love the Celestial Room, where I often see couples weeping together, families embracing, single men and women bowed in prayer.

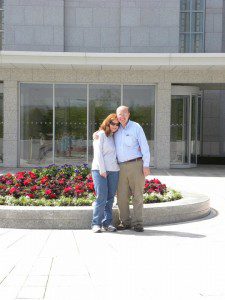

I love the memories I have of temple moments–most recently, seeing my dear father in the temple to do the last session he will do in this life. I had invited many of his friends, former students, his missionaries, to be with him. It will perhaps be my sweetest temple memory of all, though it’s too early to say. I have some years before me.

Dad was doing badly at dialysis when I sat with him there yesterday. I understand that his time on earth is waning–though we have been granted much more time than we’d anticipated. I anoint his feet with olive oil when I visit him, and massage it into his skin. I realize that this is a ritual for kings, and that I pay tribute to his beautiful feet.

When Dad announced a year ago that he would walk again (he had broken his femur), I said, “Of course you will.” I didn’t mean in this life. I was thinking of the scripture which also counsels us how to receive instruction and continuous inspiration in the temple or in whatever sacred ground we choose. If we resist any but our own answers to the deepest questions, we will make easy–and short-sighted–conclusions. We will stop short of the understanding we might have had, and will find ourselves repeating worn-out excuses or even mocking cliches. The instruction is here:

But they that wait upon the Lord shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings as eagles; they shall run, and not be weary; and they shall walk, and not faint.

When my father dies, I intend to stay with his body for several hours. A friend told me that brain waves continue for about four hours after death. I will speak to him, though he be dead, of the joys our family shared. I have forgotten anything regrettable, and find no need to search out bad memories. Let the good memories shine, polished with the love which death consummates. I will speak grace into the last glimmers of his mortal life, and celebrate his faith with my own.