I have a fertile imagination. That is, perhaps, an understatement. I wonder if each of us lives life differently, sees our life events differently. I am usually in a poem, composing a poem, and reading a poem simultaneously. I say that metaphorically. When I played Nora in Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, I said the lines, acted the part, and also recognized the unity of the script. My imagination follows trajectories. I am, as my husband has said, “leapingly intuitive.” I leap from image to image, thought to thought, not in a particularly structured way but bounding with creative energy. I leap from fact to fiction easily, cracking quick jokes or imagining people I meet in various stories. I practice “what iffing” constantly, but not consciously. And so, as I have seen my father decline, it has been natural for me to leap into imaginings that we are near to death. Indeed, we have been near twice over the past three years. That Dad has had eight years (this month!) of dialysis says that he has written his own story, defied death, and continued. We are now at another juncture where it seems to me that death is courting him, and that he may accept the invitation. Still, the gifts of my imagination call me to minister to my dad because I see waning time. I don’t want to waste a moment. My family considers me “dramatic.” Yes, I am that. But my imagination has led me to intuit rituals I should perform–anointing my father’s feet and rubbing them as a sign of honor and of comfort.

I love Star Trek: The Next Generation. In one episode, the captain of the ship (Picard) appears to have been killed. Actually, he has been mentally transported to a place where he lives an entire lifetime, marries, has children, learns to play the flute. Then, abruptly, he is returned to his previous life and is brought back to consciousness, and apparently no time has been lost. He is told that he was given that life so that he would preserve the memory of a planet which no longer exists. The inhabitants, knowing that their planet would soon be gone, wanted to leave their legacy in some future mind.

This was the episode I had in mind when I told Henry Lisowski, a former student of mine as well as missionary in our MTC branch years ago, how much I wanted him to meet my dad. Of all the missionaries I wrote to, Lisowski had a special curiosity about my dad and linguistics. I believe that Henry has the gift of tongues (which does not always include perfect Parisian grammar), and I wanted him to have a memory of my father’s face and words and testimony. It mattered to me to have Henry carry my father’s legacy, and perhaps at some time in the future, recall something my father said.

When Henry was my student, our class visited the Museum of Art, which was featuring the works of Carl Bloch.

This is how I remember that day:

My parents arrive after my students are already touring the museum. I have Dad sit in a wheelchair so he won’t get too tired, and I start wheeling him around the museum. We see several sketchings–the Lord wearing a crown of thorns; His body being taken from the cross; Mary and John leaning against each other. Directly before us is a large painting of the Savior at Gethsemane being comforted by a female angel, whose head leans over his. Tendrils of her blonde hair meet His hair. She is maternal and utterly at peace. The Savior looks exhausted. Dad and I gaze at this painting and I contemplate the many ways my family has found comfort over the past while, and the people who have cared for my father at times when it appeared we would lose him very soon.

All of the depictions of Jesus represent the stories I learned from my earliest years. They have been given to me as the most important gift and legacy of faithful parents, who yearn for me to treasure them, make them my own, learn to understand and love them not only as stories but as part of my own identity, and then pass the stories and the love down to my posterity.

We move through the museum, talking about the paintings. I am having a hard time restraining tears because I am keenly aware of the beauty which surrounds me, and that all of these pictures are precious to me because of the family I was raised in.

We come at last to the room where the painting of the Daughter of Jairus is displayed. Henry is in that room. I whisper, “That’s Henry Lisowski.” Then I wheel Dad up to the painting. He asks me to read the description, printed next to the art. It talks about Bloch’s choice to paint the scene of Jairus’ daughter at the moment of greatest despair–as the mother grieves her daughter’s death. It suggests that the mother has probably been with her child throughout the night, suffering with her. But there, at the open doorway, dawn shows, and the Savior is there. We are caught in the moment right before Jesus will enter and say, “Talitha” [little lamb], arise!” I read the words to my father, but take a long time to get through the last sentence, which says, “A miracle is about to happen.” I can picture the scene as if I were seeing it from a distance: There I am, holding the back handles of the wheelchair, fully understanding that I will not have my father for long. My father, who has grown so old and frail, fights tears. Together we are gazing at the image of death, and simultaneously at the the image of Jesus Christ, who is the resurrection and the life. Both of us are secure in our testimony that the Lord will stand in an eternal portal to greet my father when his time on earth is up, and that He will also command him to arise on Resurrection Morning. We know we will be comforted, but we surely will go through the moment of death.

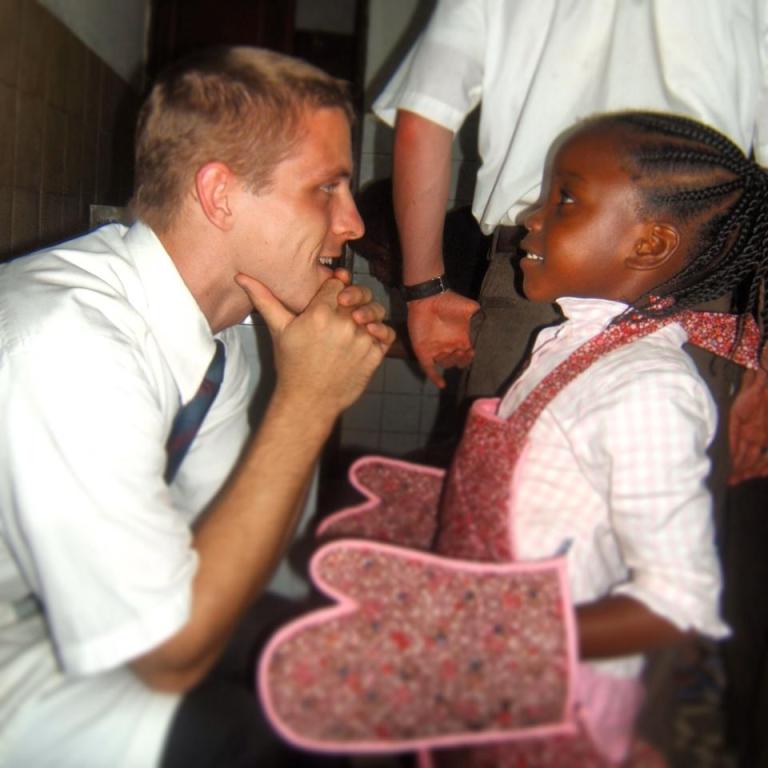

Then I wheel him to Henry. I have shared stories about my dad with Henry, and I have shared many of Henry’s missionary emails with Dad, including the final one of his mission, in which he bore strong testimony of the very things the scenes in the museum depict. Dad knows about the polio epidemic in Pointe Noire, and the story of Prince, who was healed through the power of a priesthood blessing, with Henry Lisowski sealing the anointing. Dad has been a mission president, and Elder Lisowski was the kind of missionary he still cherishes. They shake hands, the young man who has learned to love Africa and to speak French, and the old man, who has traveled the world as an ambassador for the Lord in many countries, and has learned many languages.

After we leave the exhibit, we all talk for a bit, and Dad tells Henry a little about the promises of his patriarchal blessing, and about times when he indeed had the gift of tongues, when the need was great and words were given to him which he had not known before.

And the meeting has happened. My own miracle. Henry now has the image of my father in his mind. He has a memory of speaking to this man who I believe will yet have an impact on him, because I believe that Henry will do things with langauges, including computer languages.

Our talk is fairly short because Dad needs to prepare for dialysis, but it has HAPPENED. I even took pictures with my cell phone, though the pictures are rather blurred and ghostly. Still, I have that bit of proof that the man I told Henry about, and the missionary I told my dad about, met face to face. The proof won’t matter much. It’s the memory which will abide.