I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken. (Oliver Cromwell)

I beseech you, in the bowels of Christ, think it possible you may be mistaken. (Oliver Cromwell)

Daniel Choc was one of Dale Grover’s most ardent supporters, having lived on the plantation for two years, the beneficiary of Dale’s good work and training. He had returned to his home in Patzicia when I met him in 1975. He–the same age as the missionaries Dad was training to speak Cakchiquel–became Dad’s main assistant. Often, Daniel became an angelic voice whispering translations to the missionaries as they expressed themselves in Spanish. “Yo quiero chocolate,” a missionary would say, and Daniel would whisper into his ear, “Yin ninwajo chocolate.” “Dame el pan.” “Ta-ya chwe yin ri wey.”

Earlier, on Dale’s plantation, Daniel had been a diplomat and a peacemaker.

When disagreements had arisen between Dale and the mission president, Harvey Glade, Daniel had said, “If it’s only a misunderstanding, then let’s write letters!” He, with his third grade education, led the others in a letter-writing campaign. Dale also wrote a letter, which was not well-received.

I have no way of knowing what Dale’s letter said. I do know that he was determined to have his foundation be in partnership with the LDS Church, something the leaders resisted. As I have studied peacemaking, I am struck by how much each of us usually contributes to “disagreements.” This quote from The Anatomy of Peace, published by The Arbinger Institute, is instructive:

“The more sure I am that I’m right, the more likely I will actually be mistaken. My need to be right makes it more likely that I will be wrong! Likewise, the more sure I am that I am mistreated, the more likely I am to miss ways that I am mistreating others myself. My need for justification obscures the truth.”

I have focused my life to learning more about building peace, as I certainly was no expert during my Guatemala years. In fact, I had much in common with Dale in how I viewed the LDS Church and its leaders.

I suspect that Daniel’s life and my father’s support of Dale’s work influenced the mission president, who presided during the time we were first in Guatemala. President Robert Arnold made Dale the District President in the Coban area. From all appearances, Dale was an authorized agent of the Church, heroically offering “the good life” to hundreds of Kekchi Mayans.

After a few months of being Dad’s assistant, Daniel was called to be the first Cakchiquel Indian missionary. His family, along with the CujCuj family and others, had gone to the Mesa, Arizona temple to be sealed.

I can picture Daniel perfectly. He was joy personified-short, squat, and perpetually grinning. He laughed at the missionaries’ attempts to speak his language, but never mocked. And halfway through the training, Daniel received a call to serve as full time missionary. He would be the first Cakchiquel Mormon missionary. A new day had arrived, a day when the gospel would come not just from white Americans, but from one who knew the Cakchiquel people because he was one of them.

That was 1975. My family returned to Utah in May, moving from the mists and canyons and adobe huts of Guatemala to the mountains and well-wired condominiums of Provo.

The next February, around midnight, Guatemala was hit by an earthquake, the epicenter only a fifty miles from Patsun. Twenty-two thousand people-mostly Cakchiquel Indians perished as their adobe collapsed around and on top of them. Daniel Choc’s pregnant mother was among the fatalities, as were two of his siblings.

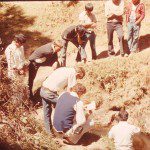

A month after the quake, Daniel and other Mormon missionaries were helping with the reconstruction of Patsun. He was taking down a wall when one of the missionaries yelled in English, “You guys, it’s going to fall! Get out of there!” Daniel stood still and then tried to get out of the door. It was too late. The wall came down on him. He died within fifteen minutes. One of the missionaries whom Dad had trained in Cakchiquel, Elder D. Warnock, took Daniel’s body, covered by a sheet, to his father, Pablo Choc, in Patzicia.

My next stop was Patzicia, where Daniel was buried.

Many who had died the previous year in the quake had been buried in mass graves. Generally, the Cakchiqueles bury their dead in colorful crypts like thin mountains. The coffins are placed and cemented, one grave on top of another. It’s a highrise of death. Daniel’s grave, however, was set apart. The Church had donated money for this particular memorial. His grave, the size and shape of a refrigerator, was painted white and bore a headstone engraved with a gold-leafed Angel Moroni and a scriptur e: “Cuando os halláis en el servicio de vuestros semejantes, sólo estais en el servicio de vuestro Dios.” When ye are in the service of your fellow beings, ye are only in the service of your God. I think President Arnold probably selected that scripture.

e: “Cuando os halláis en el servicio de vuestros semejantes, sólo estais en el servicio de vuestro Dios.” When ye are in the service of your fellow beings, ye are only in the service of your God. I think President Arnold probably selected that scripture.

When I returned to the devastated area (I could not locate any recognizable landmarks), Daniel’s grave was easy to find. I remember saying only three words when I looked at the grave: “Pues si, Hermano.” I could not imagine that one so full of life could have been stilled.

After visiting the grave, I decided I would live in Patsun, where our family had stayed the year before. There, I lived with a Cakchiquel family. I slept on a mat, ate in a hut, and learned how to clap out tortillas, Patsun style. My father thought it was a wonderful place for me to stay, and visited once, proudly stating, “You speak the worst Spanish I’ve ever heard. You sound just like an Indian.” It was true. I spoke Spanish with Cakchiquel grammar.

I could not stay with the family, however, because the father–the branch president–tried to seduce me. I spoke with two of the RMs whom Dad had taught, and they encouraged me to find different housing. I also thought the mission president should know. President Arnold had now been replaced by President O’Donnal. I had to travel to Quetzaltenango–several hours away–to see him. I already knew he was Dale’s nemesis. When I told him what had happened in Patsun, President O’Donnal said only, “You stay away from him.” It wasn’t the answer I expected to my revelation that the branch president had touched me inappropriately, and it verified my bad opinion of the new mission president.

I subsequently traveled to Dale’s place, where my father, with a man named Dean Black, was preparing for new projects: radio shows focused on literacy and health education. Couldn’t we, like Dale, affect hundreds?

Because I was with my father at the plantation, I was included on a trip to the city of Chulac. There, I witnessed the conversion of hundreds to Mormonism. And back at the plantation, I joined in the enthusiastic bashing of the mission president.

Forty years later, J.B., one of the missionaries who taught the Kekchi in Chulac, said to me, “I had forgotten that you were there [in Chulac] on the most important day of my mission.”

For some reason, I was at the right place and at the right time to live through details of the story I would later fictionalize in Salvador.

I left Guatemala earlier than I had planned, however. The mission president complained about me to the area authority, Elder Asay. He described me as hippie-like and one who took advantage of the members by living with them. I was then in Momostenango, having left the dangerous situation. I received a terse telegram from my father telling me that I needed to get home to the U.S. immediately. At the time, I was enraged, and so was my dad. I was not a missionary! How on earth could President O’Donnal presume to tell me what I could or could not do? Wasn’t he treating me just like he treated Dale?

In 2016, I completely understand President John O’Donnal’s perspective, and I honor him.

To be continued. . .

This photo shows Daniel Choc performing his final baptism, after the earthquake.

This photo shows Daniel Choc performing his final baptism, after the earthquake.