Some years ago when I was serving as Canon Educator at Washington National Cathedral, I invited Jack Miles to speak as part of a program devoted to what we called The Changing Face of God. Miles had written a New York Times best seller called, God, A Biography, that – among other things – explored Old Testament images. It was an intriguing book and I expected him to make an interesting contribution to the topic we were exploring.

The Religious Audience-Performer Model

What I didn’t expect Miles to talk about was the fact that he was once a Jesuit priest. Miles noted that he had left the Jesuits because – to paraphrase his remarks – he had tired of praying, preaching, confessing, singing and believing the Christian faith for others. In short, he had grown weary of what I have described over the years as the religious consumer – religious performer model for “doing church.”

This model, which has a strong hold on the American church across denominational and non-denominational lines, has been strengthened by a number of trends:

- Our tendency to commodify everything,

- Our obsession with numbers,

- The ways in which we tie those numbers to notions of success,

- The failure of religious leaders to take laypeople seriously as bearers of the church’s message,

- And a certain brand of clericalism that revels in the role of performer and promotes the infantilization of the laity.

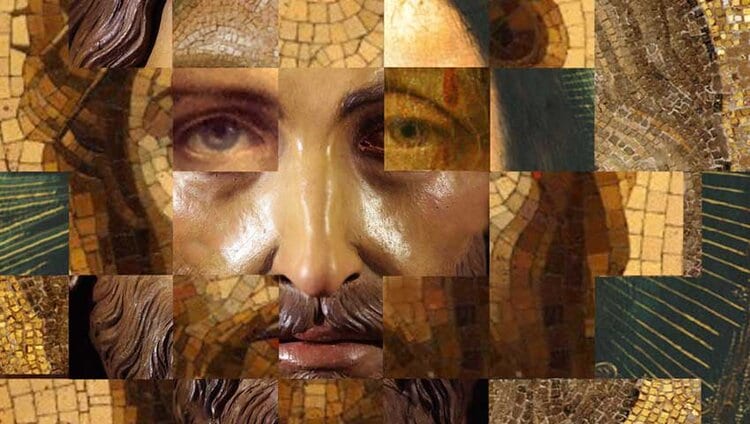

Customizing Jesus

The net result is an endless stream of programs designed attract “customers” and an equally endless series of demands from those “customers” to accommodate their needs. This pattern alone would be corrosive of church life, but it also drives other patterns that compromise any understanding of the church’s life on offer in the New Testament.

Among the most problematic are these:

- It turns disciples into consumers.

- It drives a form of entitlement that insists on endless accommodations to customer demands.

- It erodes the commitment of Christians to their own churches.

- Worst of all, where that model dominates Jesus is customized, cutting and trimming the Gospel, to suit the needs of his followers.

This way of thinking about the church contrasts sharply with the picture of the church which Dietrich Bonhoeffer outlines in The Cost of Discipleship, the very name of which outlines how differently message of Jesus resonated with the early church. It is, in fact, difficult to imagine today’s church accomplishing what the early church accomplished. The marginalized church of the first centuries and the mission work of the church around the world saw itself as a body of believers who were blessed in order to bless others. It embraced risk. It lived and it died for the sake of the Gospel. In many parts of the world, the church continues to make those sacrifices. But, it must be said, the magnitude of those sacrifices are relatively trivial in places like North America and Western Europe.

Adapting Ourselves to the Call of Christ

No one in their right mind who has ever been engaged in pastoral ministry would argue that church life ought to be made difficult simply in the name of being difficult. That would be obtuse in the extreme and difficulty as an end in itself has no meaning. Indeed, part of the reason for defending religious liberty where it still exists in the world is based upon the recognition that such freedoms are a gift and an opportunity. But the example of the church in other parts of the world and at other times in the church’s history when that freedom has not been available does suggest that it is a blessing that should be used in the name of blessing others, not in the name of customizing Jesus to suit our needs.

So, how should the church use that freedom?

When I was first taught ecclesiology (i.e., theology of what it means to be church) years ago, much of the conversation revolved around how engaged the church should be in the life of the world around it. Should it be involved in the world? Should it merge its influence with other institutions? Should it separate itself from the world around it and if so, how much?

Those are important questions. But I’ve come to the conclusion that they are not the most important and certainly not the only questions we should be asking, in large part because it leaves another, more basic challenge unanswered: “What is the church itself meant to be?” Without an answer to this question it is impossible for the church to answer the others in any grounded fashion.

The answer, of course, is the church is “the body of Christ” and as such, it is the embodiment of the new order inaugurated in her Lord and the purpose of the church is to give Christ’s new order its fullest expression. Or as the Edinburgh Conference on the nature of the church put it so emphatically years ago:

the Church is the Body of Christ and the blessed company of all faithful people, whether in heaven or on earth, the communion of saints. It is at once the realization of God’s gracious purposes in creation and redemption, and the continuous organ of God’s grace in Christ by the Holy Spirit.[1]

The church, then, should use its freedom to bless the world, not bless itself. But it can only do so in obedience to its Lord, not in customizing his demands to suit itself and there is, then, no room for performers or audiences, only disciples.

[1] F. W. Dillistone, “How is the Church Christ’s Body?: A New Testament Study,” Theology Today 2.1 (1945): 56.