Increasingly social scientists and others are noting that politics have become the new American religion. This is a claim that many have been making, including John McWhorter, who is associate professor of English and comparative literature at Columbia University; Emilio Gentile, who is an Italian historian who specializes in the study of fascism; and countless other opinion writers.

This judgment is not just a construct or an educated guess. Studies conducted by the Pew Foundation over the years suggest that politics are not only the new American religion, politics are more likely to divide families than religion. For example, thirty percent of Americans are married to people of another faith, but only ten percent of us are married to people who belong to another political party.

But that is just one indication of a larger trend. One summary of the Foundation’s work notes:

At the same time that religion is becoming less important in our lives and relationships, politics is becoming more so. Indeed, partisan identification is now a bigger wedge between Americans than race, gender, religion or education level. According to a 2017 Pew survey of more than 5,000 respondents asked about 10 political issues — from government regulation to same-sex marriage — there was, on average, a 36-point gap between Republicans and Democrats. When Pew first started asking those questions during the mid-1990s, there was just a 15-point gap between Republicans and Democrats, a divide not much different from the one between Americans of different faiths. Tracy Preminger thinks religion in her generation has become a lot less black and white. “People find their own communities and ways of practicing. But politics is becoming more divisive.”

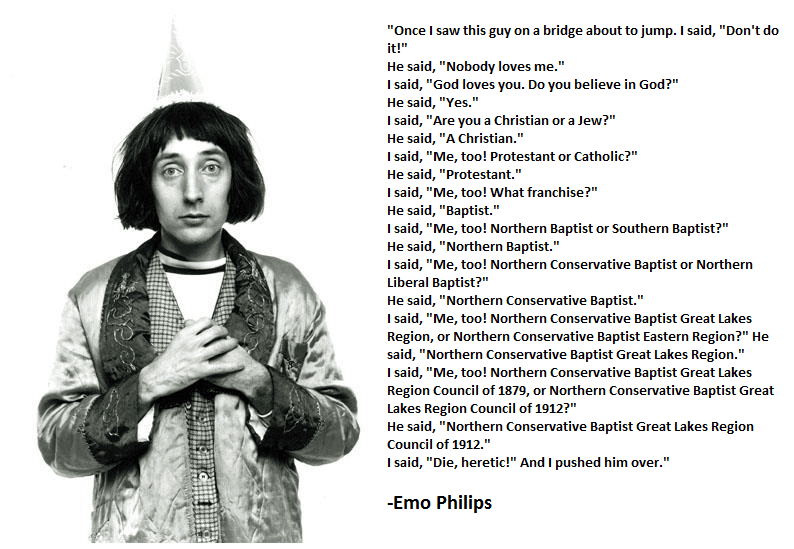

As the summary notes, there are many factors to consider when assessing the role of politics in American life, including the decline of religion. But perhaps it is also time to acknowledge that if our politics have become our religion, then we aren’t just religiously political, we are becoming a nation of political fundamentalists.

Just exactly what constitutes fundamentalism is a fraught question, and scholars are divided on its salient characteristics – particularly as that concept applies across cultures. But a distillation of some of the more common lists include:

- A totalizing view of the world

- Dualistic thinking

- In-group/out-group thinking

- Intrusive enforcement mechanisms

- Demonization of the other

- An emphasis on imminent catastrophe

- A sacred text or core beliefs

- And their unreflective application

In a forum that allows for a longer discussion, it would be helpful to describe these characteristics at greater length, and it would be useful to plunge into the debates over the strength of various definitions. But for my purposes here the list is self-explanatory and its relevance for our contemporary environment is obvious. All eight characteristics are a feature of today’s public discourse.

Thank God, ultimately, the factor that always subverts religious fundamentalism is the Gospel itself. But it is not clear that political fundamentalism, right or left, possesses the same capacity for self-correction.

On that score, it is worth listening to Leon Kass, who recently observed that it is secularization and the loss of a unifying religious vision that has caused the rupture in American civic life. However generic that vision might have been, it had the capacity to galvanize previous generations. But now, we have not only lost that vision, we have been taught to despise it.

If Kass is right, then Heaven help us – because we won’t be able to help ourselves. And none of us are safe, caught as we are between two, countervailing forms of fundamentalism that has no larger commitment that take them to task. To quote Pogo, “We have met the enemy and he is us.”

Photo by Ehimetalor Akhere Unuabona on Unsplash