Most of us are aware of the massive cargo ship that blocked the Suez Canal for six days last month. One of the most fascinating images of that event were the satellite photos of the ship and the incredible number of other ships that were blocked from passing through the canal.

Inevitably, of course, one wag picked up on the satellite image and created a meme out of the photo, adding the caption, “Don’t worry. Everyone makes mistakes. It’s not like you can see it if from space.”

I wonder if Thomas ever feels that way about our Gospel account: “Don’t worry, Thomas. Everyone makes mistakes. It’s not like billions of people are going to read about it over and over again – for thousands of years.” I’d certainly feel that way.

And last Sunday, there it was again.

Of course, there are those who try to help Thomas. The sixties yielded a series of sermons that people draw on to this day that made Thomas the patron saint of doubters and asserted that it wasn’t just alright to have questions, it was far better (and more mature) to live there.

But the problem with that reading of John’s Gospel is that there is nothing to suggest John or Jesus had that in mind.

Thomas is not offered up as a model, contrary to what we might like to think. Jesus embraces him. But according to Jesus, those who are blessed are those who believe without seeing.

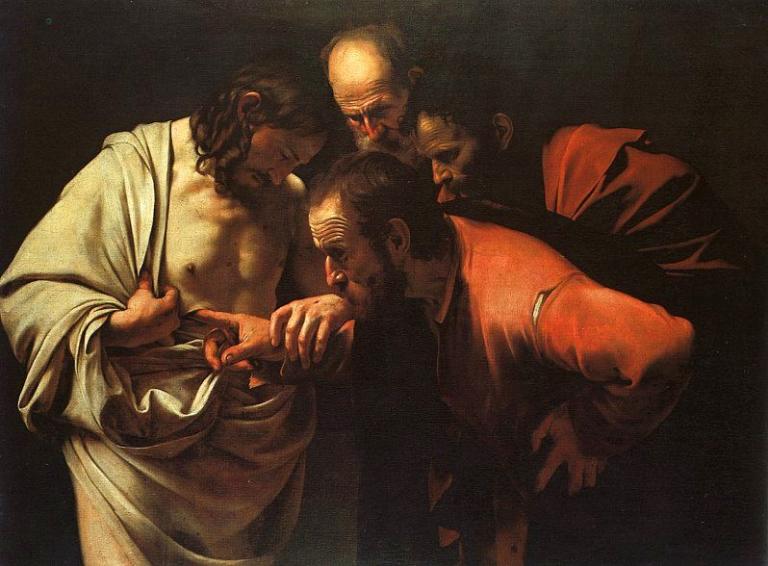

The other problem with that reading of the story is the reaction of Thomas himself. When Jesus presents himself to him, from what we can gather from the account, Thomas doesn’t end up availing himself of the offer to probe the wounds that Jesus sustained – contrary to what the powerful image created by Caravaggio suggests above. Instead, Thomas offers up a confession of faith and adoration in what many scholars argue is the climatic confession in the Gospel: “My Lord and my God.”

So, while nothing in the Gospel of John suggests that either Jesus or the church should be closed off to answering questions, clearly the point of the story is not that paralyzing doubt is a good place to live on a permanent basis.

So, what is the point that John is trying to make and that Jesus is trying to drive home here? The answer, it seems to me, is wrapped up in the nature of John’s Gospel and the place of this story at its end.

Unlike any of the other Gospels, John’s story is organized around a series of semeia or signs. Each thing that Jesus does points to the nature of the new world that Jesus, as logos, as one with the Father and the Spirit has been bringing into existence. And with each sign that Jesus offers, there are lengthy explanations of what Jesus is doing. But, more importantly, throughout the Gospel Jesus also explains how those who follow him can become a part of that new reality.

More powerfully and more explicitly than in the other Gospels, John paints a vivid picture of Christians as those who are grafted into the body of Christ and – like a branch that is grafted onto a vine – participate in the life of Christ himself. Few of us can quite grasp what that means, given the distance at which we live from farms and vineyards.

But a fair and sound analogy would be to imagine that what Jesus is suggesting is on the order of being surgically transplanted into the body of Christ. What John envisions are Christians who no longer live in isolation from one another, but are in life-giving relationship and dependence upon Christ and upon another. His life is our life, his nourishment is our nourishment, his blood is our blood. And the stronger and more vital that connection becomes, the more we become one with him and he becomes with us.

That isn’t just a spiritual or mystical reality. For John it is a very concrete reality as well, because the same Word, who was in the beginning is now in the process of changing the world that is enthralled to sin, suffering, cruelty, and death.

John goes onto suggest that this reality is deepened and reinforced by our participation in the sacraments. We are baptized into the life of Christ and every time we partake of the sacrament of Christ’s body and blood we are not just doing something symbolic, we are physically, spiritually, and emotionally transformed.

So, what does this have to do with the story about Thomas? Well, the story of Thomas, along with other accounts that record the appearance of Jesus to both Marys and the disciples appear near the very end of the Gospel, after all the signs or semeia have been completed. And they focus on the struggle they encounter in coming to grips with what has happened in the death and resurrection of Jesus.

The Thomas story is told in order to help us understand how to be a part of the new reality that Christ has invited us to embrace. And, if I was going to distill the message of this story in categories that are only slightly more modern but faithful to John’s message, I would say that his advice is this:

Seeing is not believing. If the Christian faith is going to change our lives, we have to surrender our lives to Jesus. We need to let his life become our life, his way of being become our way of being, his passion and mission become our passion and mission.

You see, there is no uninterpreted event in life. The death and resurrection of Jesus is either God’s effort to retrieve us from the mayhem and ugliness that we have created by trying to be our own gods. Or it is nothing at all. And until we give ourselves to that life and live out of it, we can’t begin to know what that life will look like or see the connections it might have with the life of Jesus.

It’s a bit like marriage, which is why Scripture compares the relationship between Christ and his church to marriage. We can’t know or say what a commitment of that kind will look like until we give ourselves to it. We will never know what all of it will mean until the day that our deaths separate us from one another. Conversely, if we enter into a relationship of that kind, but we never give ourselves fully to it, if we pride ourselves in holding it at arm’s length, then we never will know what it’s like.

And, so it is with our relationship with God. Sunday after Sunday, we take in his life. We surrender to it. We let his life become our life, his way of being becomes our way of being, his passion and mission becomes our passion and mission. And, day after day, listening for inspiration, for his guidance and wisdom, we are changed.

Seeing is not believing. Believing is the beginning of seeing.