John said to the crowds that came out to be baptized by him, “You brood of vipers! Who warned you to flee from the wrath to come? Bear fruits worthy of repentance. Do not begin to say to yourselves, ‘We have Abraham as our ancestor’; for I tell you, God is able from these stones to raise up children to Abraham. Even now the ax is lying at the root of the trees; every tree therefore that does not bear good fruit is cut down and thrown into the fire.”

And the crowds asked him, “What then should we do?” In reply he said to them, “Whoever has two coats must share with anyone who has none; and whoever has food must do likewise.” Even tax collectors came to be baptized, and they asked him, “Teacher, what should we do?” He said to them, “Collect no more than the amount prescribed for you.” Soldiers also asked him, “And we, what should we do?” He said to them, “Do not extort money from anyone by threats or false accusation, and be satisfied with your wages.” (Luke 3.7-14)

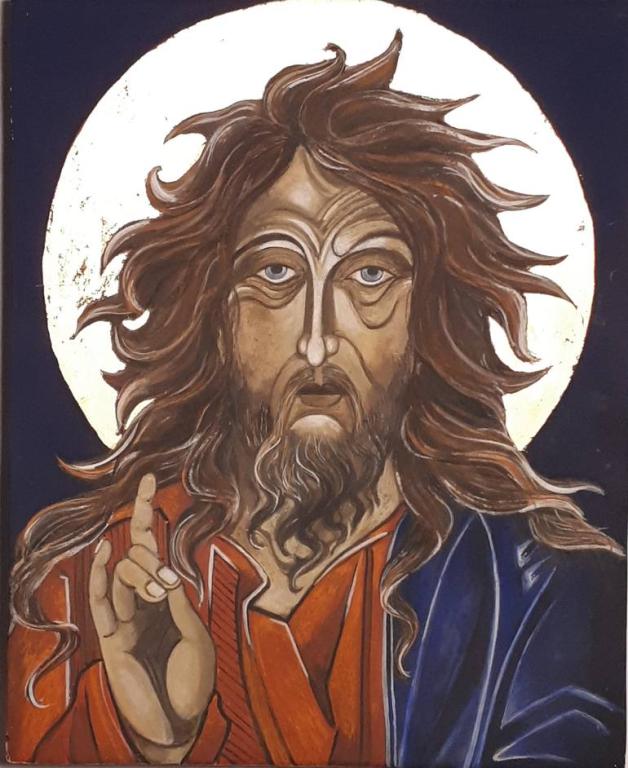

There is a meme out there on social media that tries to take a bit of the edge off of John’s message, while offering up some hard news about Advent as well. It is an image of John, looking for all the world like a wild man from the back side of the desert – which is probably more or less what he looked like – with the tagline, “Happy Advent, you Brood of Vipers!”

I understand the ambivalence. I think we probably come to John’s words in the same way that his contemporaries approached them. This is a cold shower. A slap in the face. A shock to the system. And there are any number of reasons we don’t want to hear it.

Some of us come to John’s message fairly certain we have our religious pedigree in place. We may not be the children of Abraham. But we have found the equivalent in our own world. We may be cradle Episcopalians, or we may have tucked into that peculiar niche in the Episcopal Church that is the perfect blend of religious, cultural, and political commitments. Or maybe we’ve just settled into the conviction that we are basically good. That’s a comfortable place to live, and it’s surprisingly easy to hold God at arm’s length when you live there.

We have other reasons for running from John, too: We don’t want to be wrong. We don’t want to be judged. We don’t want to be disturbed by the revelation that we don’t live in a fashion that is congruent with the things we claim we believe.

Then, there is that deeper, cultural reason for ignoring the madman from the backside of the desert. Like John, we are convinced that living with integrity is exactly what life is all about. But we are equally certain that we are the ones who get to define what that means. In fact, we are adamant about it.

All of that came to a point when people went out to see John. Notice, they didn’t just run into John on the street. They went out, into a deserted place. And they didn’t just go out there to hear him talk. They went out to be baptized.

And what does the ungrateful wretch do? John calls them names. He tells them their motives for showing up are self-serving. And then – to make matters worse – he tells them that the only kind of integrity that counts involves aligning their lives with the act of repentance.

When they asked him, “Then, what should we do?” John pressed his point further:

- Those who have should give to those who don’t.

- Those who collect taxes should not collect more than what is mandated.

- Soldiers should be satisfied with their pay. They should not extort money from those they are hired to protect.

So, what are we to make of John’s message?

All of this is about turning and changing. But even that isn’t the ultimate goal. We’ve already been told this is about straightening and leveling the way of the Lord, of making a way for the Messiah and the Kingdom of God. Of conforming our lives to God’s ways, as it is reflected in the ministry and teaching of Jesus.

This seems to be true:

- John’s message is explicitly eschatological. It is tied to what God longs to do and is doing in and through the Anointed One.

- John is not calling for a human achievement, nor is he calling for a political response in the sense that he uses the word political. Is it political in that it describes the way in which the people of Israel should order their lives? Yes, but it is not a political agenda in the contemporary sense of the word and certainly not for a secular state without an explicit religious commitment of the kind that shaped John’s faith.

- This is why John challenges the people of God, but he does not organize the reformation of Rome or even Israel in the structural sense of the word.

- For that reason, his explanation of what it means to “bear fruits worthy of repentance” does not raise questions of ownership, focus on the appropriateness of taxes, or raise questions about the validity of having or serving in an army.

- Instead, he challenges people to realign their lives in a fashion that gives expression to the priorities of God’s Kingdom and to eliminate the dominant challenges in each of their lives that presents an obstacle to the transformative work of God’s reign.

- This also means, however, that the demand he makes of those who hear him is open-ended and is constantly oriented to a life that makes a path for the work of the Kingdom.

In its contemporary application, this does not mean that Christians should not be engaged in political vocations or activities. Nor does it mean that what is accomplished in that fashion might not help to make a path for the work of the Kingdom. But it does mean that John’s vision cannot be achieved in that fashion. It also means that his challenge cannot be dispatched by achieving political goals or by ordering our collective life.

It is and remains a religious, dynamic, and open-ended challenge which is oriented toward the reign of God and one which is given further point in the teaching of Jesus.

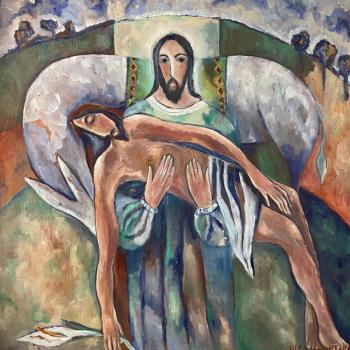

The painting is by Linda Miller Baker