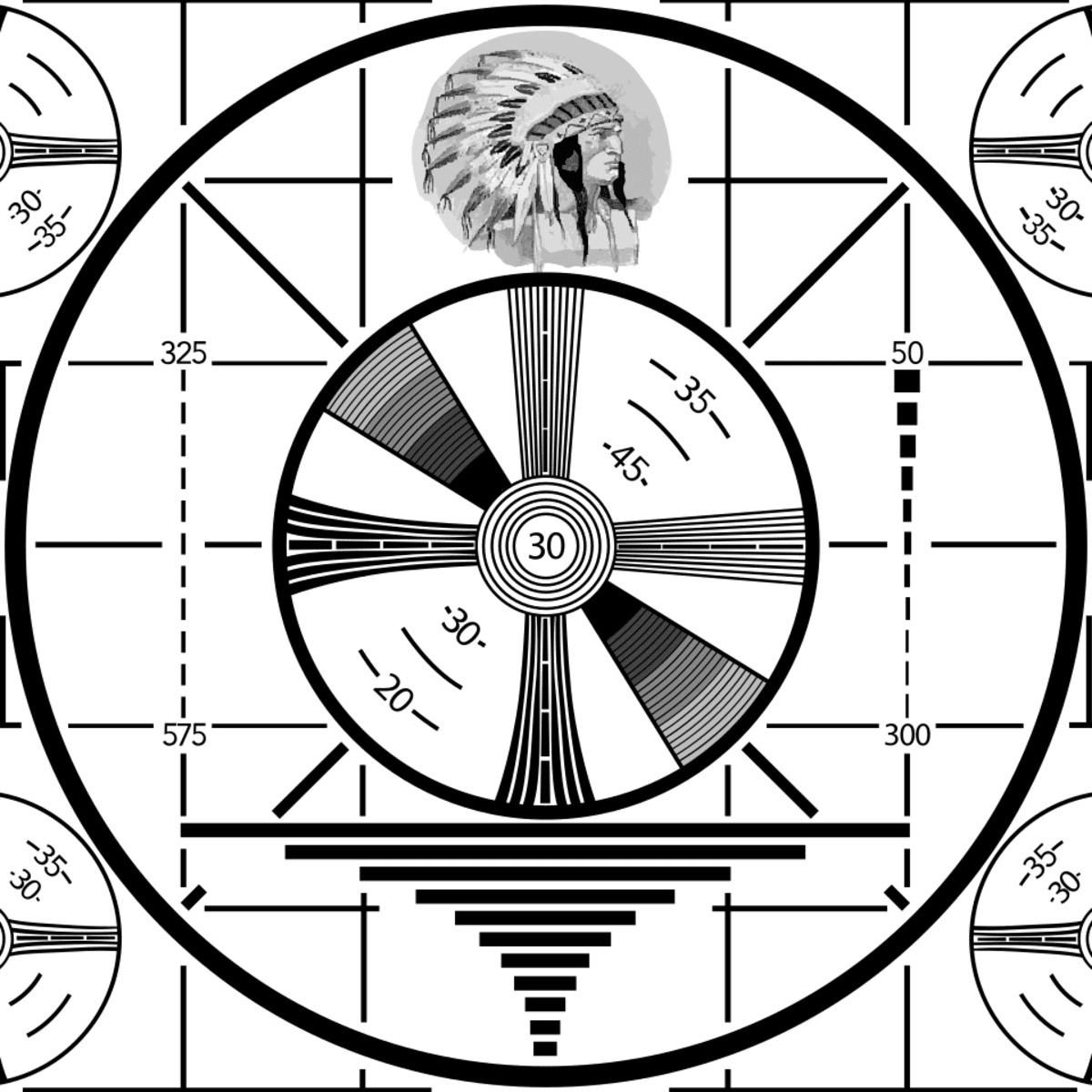

Looking back, it is hard to believe that America ever had a test pattern. It was “a test card created by RCA of Harrison, New Jersey, for calibration of the RCA TK-1 monoscope. It features a drawing of a Native American wearing a headdress and numerous graphic elements designed to test different aspects of broadcast display. The card was introduced in 1939 and over the course of the black-and-white television broadcasting era was widely adopted by television stations across North America.” I am quoting here because I only understand in general terms what that actually means.

Whatever its technical application, from 1947 onward it became an icon of the age of television, and it retained that position for the better part of thirty years. Along with the national anthem, it signaled the end of the broadcasting, and my childhood memories of it (on the rare occasion that I was up that late) seemed to slowly petering out as technological changes and the advent of color television supplanted it. For the rest of us the test pattern – along with a recording of the National Anthem – signaled the end of the broadcasting day and seemed to say, “Good night, America, sleep tight, sweet dreams.”

The demise of the test pattern isn’t perfectly congruent with the beginning of the 24-hour news cycle. But the disappearance of the test pattern and the advent of endless, cyclical news reporting and political commentary feel as if they are markers of great watershed: not just in the length of the broadcasting day, not just the news cycle, but in terms of the tenor of civil discourse. It should probably tell us something that the 24-hour news cycle began with the O.J. Simpson trial. As tragic as the events were, the focus was inarguably disproportionate and parochial. It had no bearing on public policy, and it had little or no local implications, never mind national or international significance. It was, in short, an exercise in voyeurism, driven by market share and advertising.

Of course, it isn’t easy to offer up fresh subjects for this kind of reporting. (Though heaven knows, we have done our best.) And things might have been different if the 24-cycle actually offered up detailed reporting from around the world, including countries that far too many of us don’t even know exist: Angola, Côte d’Ivoire, Namibia, Bhutan, Maldives, Brunei, just to name a few.

But we didn’t. So, as the length of the broadcasting day continued to stretch everyone’s capacity for subject matter, programmers often filled the available space with shouting matches between partisans with predictable political views. And even headlines began to multiply that were populated with verbs in the subjunctive mood, “might”, “may”, and “could” being chief among them. Predictably, the anxiety and, therefore, the attention of the American public grew in size and polarized – often not around things that had happened, but around things that might happen.

I don’t blame journalists – at least, not all journalists. I know a few of them and read the work of others, and there are many who are deliberative and careful. This is not even an argument that reporting should be freed from issues associated with market share and advertising. Reporting is an expensive endeavor and subsidized, national reporting would only lend itself to propagandistic propensities that would exercise even greater influence over the content of what we see, hear, and read

We are the problem. We need to discriminate between what has happened and what might happen, between what is news and what might become news, between events and their interpretation, between reporting and opinion. We also need to resist the recruitment implicit in the commentary of – I’m sorry, only, maybe not – “partisan hacks”.

In short, America needs a test pattern.

It isn’t likely, of course, that we will go back to it. But perhaps it is time to consider intellectual and spiritual exercises that will help break our addiction to nonstop outrage. We can:

- Read some history and get a bit of perspective.

- Read about what is happening elsewhere in the world and begin distinguishing countries from continents. This can also help us all get a bit of perspective.

- Begin reading longer, more thoughtful treatments of issues rather than the endless clickbait out there.

- Make room in our thinking for complexity. Problems are never as simple as our polarized and polarizing politics claim that they are.

- Talk to one another and, more importantly, listen to one another. Until we’ve patiently allowed someone to explain why they believe what they believe, we do not truly understand one another.

- Take a break from the news and indulge in a bit of intellectual cleansing.

And, finally, we can take regular breaks in the evening and make the effort to reaffirm the relational dimension of our lives.

If they won’t give us back the test pattern, we should make one for ourselves.