Do you remember this song from the Sunday Schools of decades ago?

Zacchaeus was a wee little man

And a wee little man was he

He climbed up in a sycamore tree

For the Lord he wanted to seeAnd when the Savior passed that way

He looked up in the tree

And said, ‘Zacchaeus, you come down!

For I’m going to your house today!

For I’m going to your house today!’Zacchaeus was a wee little man

But a happy man was he

For he had seen the Lord that day

And a happy man was he;

And a very happy man was he

You probably do. Evidently, even Alexa, the voice-activated, home-busy-body knows the words to it, if you ask her.

Amazing. No one is sure who originally wrote it, but this little ditty has worked its way into the public domain and appears in at least eleven hymnals.

The problem with it is that the song has made a strange and challenging story both sweet and saccharine . The story of Zacchaeus actually plays a critical role in Luke’s description of Jesus’s ministry and, it is the last story in the journey of Jesus to Jerusalem. So Luke uses it to recapitulate themes that he has sought to emphasize throughout his Gospel (see Luke 19:1-10).

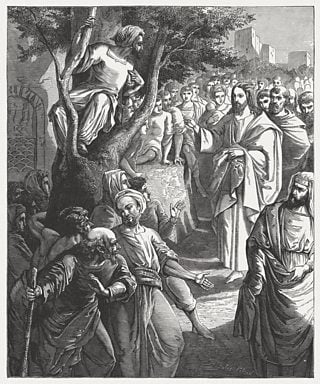

The song and the Gospel narrative suggests that Zacchaeus was little, so he climbed up in the tree, in order to get a good view. But truth be told, he probably climbed up in the tree because it was safer than being in the crowd.

No one knows exactly what a “chief tax collector” was. The term doesn’t appear anywhere in the contemporary literature of the day, but scholars surmise that it means Zaccheus was “a contract tax collector”. That is, the Romans had paid him to collect their taxes, and he got rich off of it.

If that’s the case, Zacchaeus had good reason to avoid crowds. Taxes were emblematic of Roman control over ancient Israel, and there were those who believed that paying them was blasphemous. So, helping the Romans with collecting them carried with it both religious and political overtones. To put it another way, a Jewish tax collector was both traitor and heretic. (His contemporaries were probably even less charitable, but I’ll let you fill in the blanks.)

So, Zacchaeus climbs a tree – an outcast who is curious, maybe even interested or desperate to hear what Jesus has to say – and, surrounded by “good folk”, as we say in the South, Jesus looks at Zacchaeus, perched up there, well away from the crowd and tells him, “Get down, come along, you are the one who is going to host me.”

What is striking is that Luke never tells us what that dinner was like. Judging from what the narrative offers us, Zacchaeus gets down out of the tree. And now a little more confident that the crowd won’t maul him, he takes his place alongside of Jesus, and without prompting or an effort to persuade him, Zacchaeus tells Jesus: “Look, half of my possessions, Lord, I will give to the poor; and if I have defrauded anyone of anything, I will pay back four times as much.”

Instead, all we are told is that – still standing there with the crowd gathered around him – Jesus tells them what has just happened: “Today salvation has come to this house, because he too is a son of Abraham. For the Son of Man came to seek out and to save the lost.” In other words, Zacchaeus’s relationship with both God and with the people of God have been restored, whatever they might think.

As I said, in recounting this story, Luke brings us back to the themes that he has been emphasizing throughout his Gospel:

- The Reign of God has come in the person and ministry of Jesus Christ

- That reign, that Kingdom, calls for change and it offers healing and freedom

- Healing that touches our relationship with God and with one another

- It will embrace everyone who will respond to Jesus’s invitation

- And everyone who does respond will give themselves fully to the new life and way of being that it offers, because nothing is more important

Now, why does Zacchaeus focus where he does and emphasizes giving to the poor and restoring those whom he has defrauded? There are those who point to this passage and others, arguing that Jesus talked more about money than anything other single thing.

But I don’t think that’s the answer: For one thing, even if that were true, that wouldn’t explain why Zacchaeus focuses there anyway. For another, I’ve looked through that list of passages in which money is mentioned and it simply isn’t true that it is what Jesus talks most about. Often, in fact, when Jesus talks about money it is either part of a story that actually deals with something else. And the something else is, in fact, the thing that Jesus does talk most about: the Kingdom of God.

The sounder explanation is that, for Zacchaeus, his handling of money was the spiritual obstacle that kept him from entering the Kingdom of God and receiving the healing that Jesus offered. This wasn’t just an abstract or theoretical problem for Zacchaeus. He ignored the poor and he exploited others; and both patterns had alienated him from God and from those around him.

This is no doubt why the Greek suggests that his promise is not just a once-and-done act of contrition, but an on-going transformation, which, of course, is characteristic of true repentance. In other words, his path back to God is made possible by radically changing his behavior toward that one obstacle that loomed large in his life.

We can learn from the experience of Zaachaeus, even if he was a wee little so-and-so.

Nothing, including money, should inhibit us from responding to the Kingdom. As followers of Jesus, the reign of God is our priority. And our faith requires the concrete reexamination of our lives, looking for behaviors and values that make it impossible for us to give ourselves to that life.

This is why, down through the centuries, the issue of money resurfaces time after time, even when it really isn’t the point. And that is why – along the way – the church has treated giving as a spiritual discipline.

As with Zacchaeus, giving reasserts our dependence upon God, it opens us to the needs of the community, and it does that on a recurring basis, so that we don’t lose track of either one by choice or by accident. May God use his story to move us beyond the harmless world of the “wee little man” to the challenging and freeing embrace of Jesus, his Lord.