The title of my dissertation was “Ethics and Eschatology in Selected Apocalyptic Literature and the Teaching of Jesus”. Now and then I was asked what I was working on by family, friends, and the occasional stranger. I only attempted to describe that title once. After that, I simply responded, “Jesus”.

One of the great gifts of modern academic work is specialization, the process of learning more and more about less and less. The process has its strengths. It allows a scholar to drill down and master a great deal of detail. It makes it possible to ferret out small complexities.

But specialization also has its disadvantages. One, in particular, is the ability to see the proverbial forest for the trees. In the case of Scripture, this means that we are often good at dredging up a great deal of detail in connection with a specific passage, but we are terrible at seeing the larger patterns.

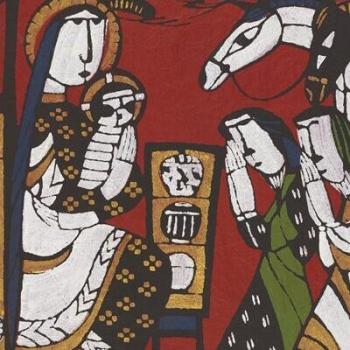

The readings during Advent that deal with Mary and Joseph are a case in point. I’ve heard countless sermons on the specifics of those passages. Some of them were even good. But it’s rare to hear Christians – particularly Protestant Christians – talk about the larger patterns associated with those readings.

Why did the Christian tradition preserve anything at all about the parents of Jesus? Why does his family figure into the story at all? And what about those stories could possibly be of significance for us?

It would be difficult to answer those questions thoroughly in a single sermon, but I would like to take a bit of time to describe what I think the significance of these passages might be for us. In order to do that, I am going to be pretty direct, because there isn’t time to develop a longer argument for what I am going to suggest here.

First, let me note that the emphasis on the family of Jesus is a natural extension of the church’s theology of the incarnation.

The church discovered in the first three centuries of the Christian era that to say that “in Christ God takes on human flesh” necessarily entails Jesus having been enmeshed in the whole of the human experience. If Jesus was just a human being deputized by God to have a human experience or if Jesus was just God in a people suit, the early church was clear: this did not describe what the Apostles claimed.

Jesus had to enter fully into the human experience without reservation. He had to be subject to its limitations. He had to experience the kind of development and nurture that is part and parcel of the journey that we all experience. This was so important that the church rejected the early efforts that some writers made to describe Jesus as what we would have thought of as a six-year-old-superhero. They weren’t just stories without historical foundation. They portrayed Jesus as a child who from the very beginning was without the limitations of real children. And while they did not preserve a lot detail from the childhood of Jesus, they clearly thought that it was much like that of any child.

It is not surprising, then, that the church preserved the memory of Jesus as the member of a family.

As an individual, Jesus could not experience everything, but the experience of being part of a family is elemental and primal. The Gospels are not biographies in the modern sense of the word. So, there is no lengthy treatment of Jesus’ birth and childhood, as there would be in a modern biography. But the emphasis on incarnation goes a long way to explaining why there are basics about the birth of Jesus and his family: Mary’s response to the angel, Gabriel; the angel’s message to Joseph; the flight from Herod’s murderous plot to have them killed; the conversation that Jesus has with teachers of the Law, when Mary, and Joseph take him to Jerusalem to offer a sacrifice; the first miracle Jesus performed at a wedding; and the last words of Jesus to Mary and John from the cross.

There is enough here that, as some of the church’s theologians have pointed out, there is every reason to believe that Mary and Joseph taught Jesus to pray. They nurtured him in their faith. They modeled the spiritual practices associated with it. And they undoubtedly encouraged him to do the kind of deep, prayerful listening that helped him to grasp and understand his vocation and mission.

More broadly, the story of Jesus, Mary, and Joseph reflects deeper truths about us as human beings, the blessings of family, and the perils that we face when families struggle or fail.

In modern America it is easy to imagine that we can do without families, and certainly there are families that are so toxic that one might argue that the children in those homes would be better off without them. I have a friend, for example, that has been so scarred by the unloving behavior of adoptive parents, that deep into life, he is still struggling with any strong sense of his own worth. And he wanders from place to place, never settling into meaningful relationships or work.

But anyone who has traversed that ground knows just how important it still is to reproduce the intimacy of a healthy home – whether it is by building friendships that compensate for a broken home or building their own families freed from the past. That is so much the case that survivors of toxic families still distinguish between families of chance and families of choice.

Marking the death of one such substitute grandfather, a friend of mine recently posted this tribute:

I left home at fourteen years old to attend a boarding high school and never lived at home again. During my high school years living on the other side of the country from my family I was “adopted” into a number of homes and families by people who showed me incredible love, generosity, and hospitality. One of those people was Art…and his wife Martha. When I visited them (as I often had the occasion to) I was always welcomed like I was one of their grandkids, home on the weekend to visit. They and their extended family showed me so much love and care and modeled many of the things I wanted to emulate in my life as a husband, father, and (eventually) grandfather. Art was a man of incredible humility, kindness, and wisdom. To use a bit of an old-fashioned word, he was “saintly”. He will be missed, but his incredible biological family and his “adopted” kids and grandkids (like me) will carry on his legacy.

What is striking about my friend’s tribute is the credit he gave his adoptive grandfather – not just for his own care – but for his capacity to care for and build his own family. Culturally, we have become so focused on professional achievements and so obsessed with politics, that we no longer recognize – not just the power – but the necessity of family.

Families can and should be a place where we cultivate our ability to love and trust; where we can learn to be vulnerable; where we can rest, reflect and grow; a place where we can learn and be nourished, emotionally and spiritually. Practically speaking those gifts make it possible for us to venture into the world, risk ourselves for others, achieve things that would otherwise be impossible, and provide us with a refuge that endures across generations.

But we have become such technocratic barbarians culturally that we have bought into the illusion that these gifts can be achieved in isolation with a google search, a bit of therapy, and a bit of help from the government. Nothing could be further from the truth and the social wreckage is on display in every city in the country. Our narrow interest in the individual and in the political has eclipsed the family, leaving us adrift in the world. Alone and on our own, to find love, acceptance, and meaning.

Nothing, absolutely nothing, can substitute for the two messages that every child needs to hear from their parents – and those messages are thread through the literature of both the Old and New Testaments:

It is good that you are, and you are loved.

You have a future, and you have God’s support and ours in pursuing it.

It is a small wonder, then, that the Christian tradition has described Nazareth as “the school of the Gospel” and the family as the “domestic church, called to pray together”.[i] Jesus comes to us, born of Mary – loved, supported, and guided by Joseph – the redeemer not just of our lives, but the one who blesses and consecrates the family.

This Advent, may we learn the lessons of Nazareth. My prayer for you is that whatever the shape of your family may take this Advent and Christmas season, that you will focus prayerfully on both the blessings you can give and those that you can receive.

May Christ remind us of the family’s value. The redeeming power of love. The healing power of forgiveness. The enduring value of wisdom nurtured among those for whom we trust and care. The gift of words that heal. The comfort of a hug. The importance of a trusted refuge. The capacity of strong families to welcome the stranger and care for the infirmed. And the gift of a faith and prayer that bears our burdens and lifts us up.[ii]

Photo by Andrew Rivera on Unsplash

[i] Pope Benedict XVI: “Dear friends, because of these different aspects that I have outlined briefly in the light of the Gospel, the Holy Family is the icon of the domestic Church, called to pray together. The family is the domestic Church and must be the first school of prayer. It is in the family that children, from the tenderest age, can learn to perceive the meaning of God, also thanks to the teaching and example of their parents: to live in an atmosphere marked by God’s presence. An authentically Christian education cannot dispense with the experience of prayer. If one does not learn how to pray in the family it will later be difficult to bridge this gap. And so I would like to address to you the invitation to pray together as a family at the school of the Holy Family of Nazareth and thereby really to become of one heart and soul, a true family. Many thanks.” https://www.vatican.va/content/benedict-xvi/en/audiences/2011/documents/hf_ben-xvi_aud_20111228.html See also: https://stboniface-lunenburg.org/the-holy-family-of-jesus-mary-and-joseph

[ii] Inspired by Pope Paul VI’s address in 1966: https://www.nytimes.com/1964/01/06/archives/text-of-popes-address-at-nazareth.html